Dozens of Syrian civilians killed in apparent chemical attack

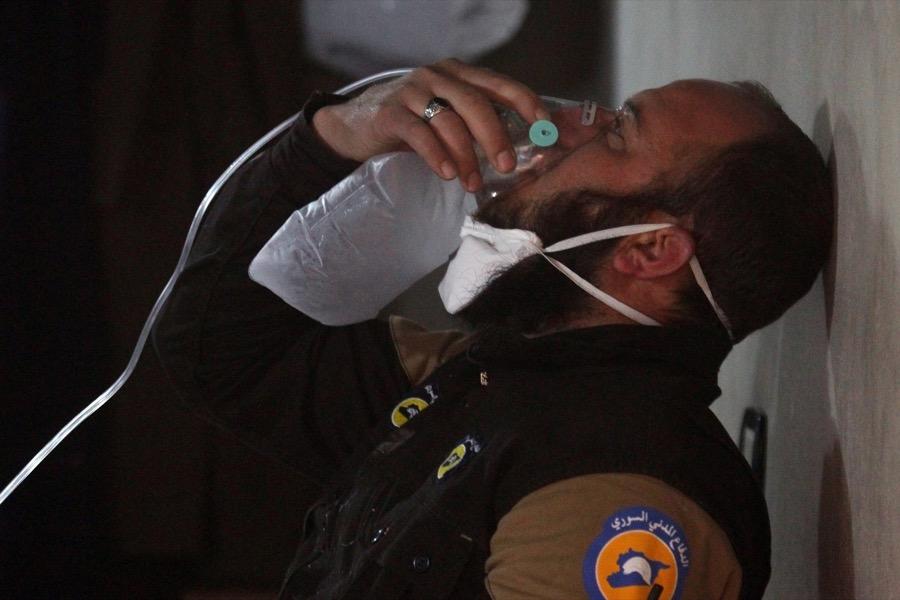

A civil defense member breathes through an oxygen mask, after what rescue workers described as a suspected gas attack in the town of Khan Sheikhoun in rebel-held Idlib, Syria on April 4.

A suspected chemical attack in rebel-held northwestern Syria killed dozens of civilians, including children, and left many more sick and gasping on Tuesday, causing widespread outrage.

The attack on the town of Khan Sheikhoun killed at least 58 civilians and caused dozens to suffer respiratory problems and symptoms including vomiting, fainting and foaming at the mouth, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights monitoring group said.

At least 11 children were among the dead, the Observatory said, and an AFP correspondent in Khan Sheikhoun saw many attached to respirators as they were treated for breathing problems.

Hours after the initial attack, air strikes also hit a hospital in the town where doctors were treating victims, the AFP correspondent said, bringing down rubble on top of medics as they worked.

Syria's opposition blamed President Bashar al-Assad's forces, saying the attack cast doubt on the future of peace talks.

A senior Syrian security source denied claims of regime involvement as a "false accusation," telling AFP that opposition forces were trying to "achieve in the media what they could not achieve on the ground."

If confirmed, it would be one of the worst chemical attacks since the start of Syria's civil war six years ago.

The incident brought swift international condemnation, with France and Britain demanding an emergency UN Security Council meeting and President François Hollande denouncing a "massacre."

'Dead in their beds'

British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson called reports of the attack "horrific" and said the incident "must be investigated and perpetrators held to account".

UN Syria envoy Staffan de Mistura said the attack was believed to be chemical and launched from the air, adding that there should be a "clear identification of responsibilities and accountability."

The Observatory said the attack on a residential part of Khan Sheikhoun came early on Tuesday morning, when a warplane carried out strikes that released "toxic gas."

As well as those killed, at least 160 people were injured, it said, and many were dying even after arriving at medical facilities.

The monitor could not confirm the nature of the gas, and said the attacks was likely carried out by government warplanes.

"We heard strikes this morning … We ran inside the houses and saw whole families just dead in their beds. Children, women, old people dead in the streets," resident Abu Mustafa said.

Russia's military, which has been fighting in support of Assad's government since September 2015, denied carrying out any strikes near the town.

The AFP journalist in Khan Sheikhoun saw a young girl, a woman and two elderly people dead at a hospital, with foam still visible around their mouths.

Doctors at the facility were using basic equipment, some not even wearing lab coats, and attempting to revive patients who were not breathing.

'Foaming at the mouth'

A father carried his dead little girl, her lips blueish and her dark curls visible, wrapped in a sheet.

As doctors worked, a warplane circled overhead, striking first near the facility and then hitting it twice, inflicting severe damage and prompting nearly a dozen medical staff to flee.

It was not immediately clear how many people may have been injured or killed in the hospital strikes.

Speaking to AFP, medic Hazem Shehwan said victims were suffering from symptoms including "pinpoint pupils, convulsions, foaming at the mouth and rapid pulses."

Khan Sheikhoun is in Syria's Idlib province, which is largely controlled by an alliance of rebels including former Al-Qaeda affiliate Fateh al-Sham Front.

The province is regularly targeted in strikes by the regime, as well as Russian warplanes, and has also been hit by the US-led coalition fighting the Islamic State group, usually targeting jihadists.

Syria's leading opposition group, the National Coalition, blamed Assad's government for the attack and demanded the UN "open an immediate investigation" and hold those responsible to account.

"Failure to do so will be understood as a message of blessing to the regime for its actions," it said.

Syria's government officially joined the Chemical Weapons Convention and turned over its chemical arsenal in 2013, as part of a deal to avert US military action.

That agreement came after hundreds of people — up to 1,429 according to a US intelligence report — were killed in chemical weapons strikes allegedly carried out by Syrian troops east and southwest of Damascus.

But there have been repeated allegations of chemical weapons use by the government since, with a UN-led investigation pointing the finger at the regime for at least three chlorine attacks in 2014 and 2015.

The government denies using chemical weapons and has accused rebels of using banned weapons.

The global chemical arms watchdog said Tuesday it was "seriously concerned" by reports of the attack.

The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) said it was "gathering and analysing information from all available sources".

The UN's Commission of Inquiry for Syria said it had begun investigating the "extremely concerning" reports of "alleged use of chemical weapons."

More than 320,000 people have been killed in Syria since the conflict began in March 2011 with anti-government protests.

Doubts on peace talks

Successive rounds of peace talks, including a UN-sponsored meeting in Geneva last week, have failed to produce a political breakthrough.

Tuesday's attack cast new doubt on the peace process, said the opposition's chief negotiator Mohamad Sabra.

"If the United Nations cannot deter the regime from carrying out such crimes, how can it achieve a process that leads to political transition in Syria?" he told AFP.

On Twitter, the head of the opposition High Negotiations Committee Riad Hijab said the attack was "evidence that it is impossible to negotiate with a regime addicted to criminal behaviour".

Diplomats at the United Nations said the emergency meeting demanded by France and Britain could be held as early as 2000 GMT on Tuesday.

"I've seen the reports about the use of sarin and as far as I know they have not been confirmed," the British ambassador to the UN Matthew Rycroft said.

"This is clearly a war crime," Rycroft told reporters. "I call on the Security Council members who have previously used their vetoes to defend the indefensible to change their course."

By AFP's Omar Haj Kadour in Khan Sheikhoun, Syria.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!