How a major American museum gave its exhibits a dye job — for authenticity’s sake

Coyote, before and after recoloring.

In 2011, the American Museum of Natural History in New York City changed out the light bulbs illuminating the dioramas in the Hall of North American Mammals in an effort to conserve energy. That’s when museum conservators realized that their displays could use a makeover.

“I liken it to when you do renovations or re-do your living room in your own home, and you might replace the blinds or the couch, and then when you do that, you realize you should really take a look at everything else,” says Fran Ritchie, a project conservator at the museum.

For example, in the bison exhibit, “the painted specimens and the background were still nice and brown, [but] then the taxidermy specimens had faded to about a blond color,” Ritchie says. “Of course, in nature, animals are different colors. Just like humans, their hair color can vary. But there is a certain point where it gets out of the natural realm of that species, and that’s the point that the museum had reached.”

Reviving the color of the animals’ fur would require a more tailored approach than historic restoration methods. In the past, museum taxidermists might have used acrylic paint or commercial dyes like those found in the drugstore, but such products would be harmful to the fragile hide of their mounted specimens, Ritchie explains. Commercial dyes generally require a lot of water, which can warp the skin, and acrylic paints make the hair feel matted and stiff, she says.

The museum found its solution in metal complex dyes, which are often used in printing inks. Such chemicals consist of dye molecules and a transition metal ion, like chromium, copper, or cobalt (the ion makes the dye soluble so that it can react with fiber). The museum conservators found that if they mixed these powdered dyes with a solvent but left out the binder, they produced a lightfast (that is, fade-resistant) medium that looked natural when airbrushed onto hair. Using these dyes, the AMNH completed the renovation of the Hall of North American Mammals in 2012.

The conservators weren’t sure how long the dyes would last before the animals would have to be re-treated, however. To find out, they partnered with the Yale University Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage in 2013, bringing together a team of conservators, scientists, and consulting taxidermists, with additional support from curators and exhibition staff.

The team’s main objective is to test and rank the metal complex dyes by their lightfastness. To that end, they’re mixing the dyes with a variety of solvents—including acetone, ethanol, and isopropanol—to find out which combinations are the most stable after airbrushing onto animal hair.

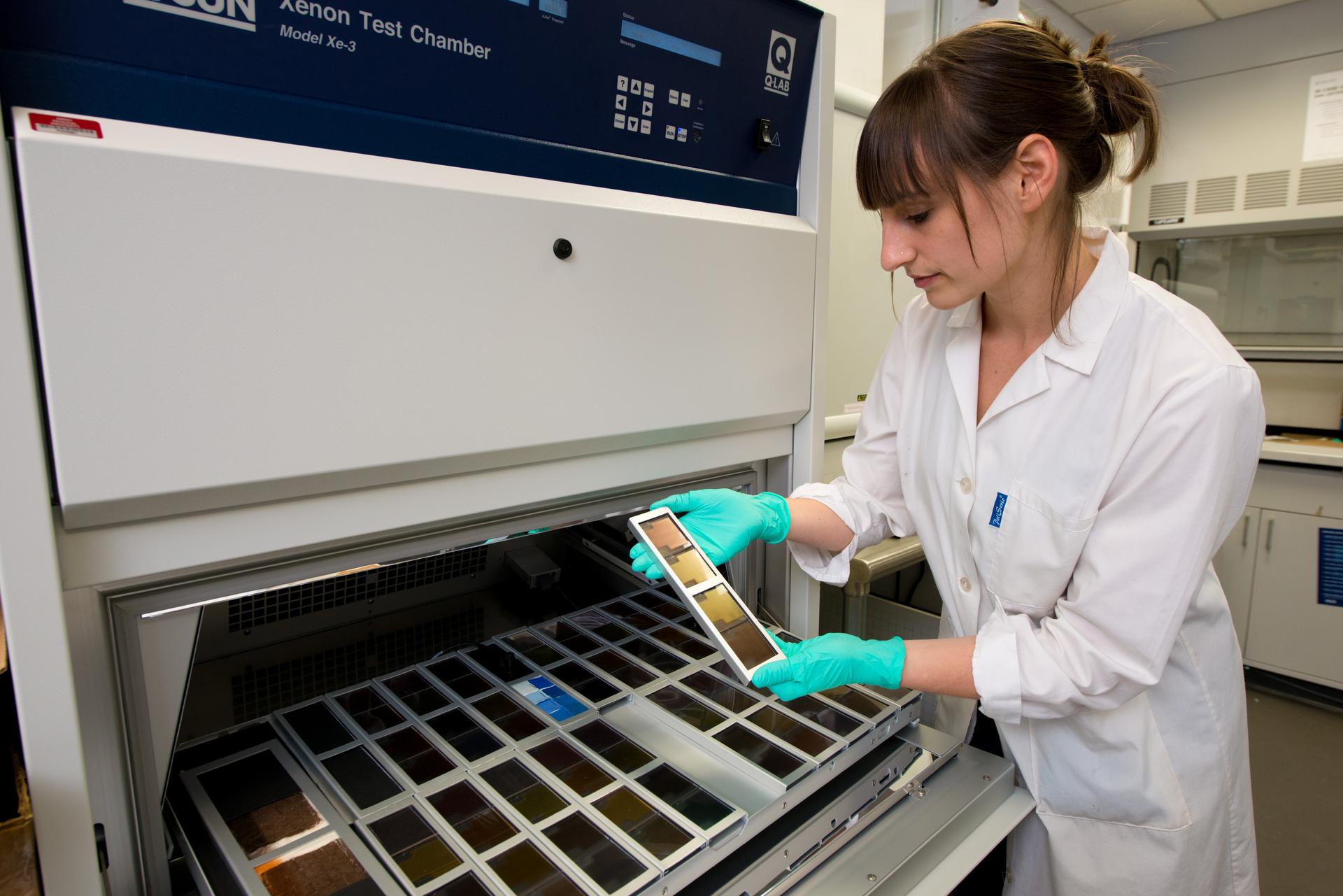

As an aid to their inquiry, the team acquired a time-traveling device of sorts: an accelerated aging chamber, which artificially speeds up the toll that time would naturally take on an object. The chamber is equipped with three xenon arc lamps that mimic daylight, and settings for adjusting the relative humidity and temperature inside.

Using the machine, conservators have already completed an initial phase of testing, which entailed studying how the dyes weather on their own, before being sprayed onto hair. They applied different dye solutions onto quartz plates — which are inert, durable, and optically pure — and then placed the plates into the chamber and blasted them with the “equivalent of three suns’ worth of energy,” says Ritchie. They also compared the aged plates to dyed swatches exposed to the museum lights, to better determine what the real-time equivalent is to a stint in the aging chamber.

The team is now moving on to a second phase of testing, which will involve spraying the most promising dyes onto white deer hair and exposing those samples to the aging chamber. Then they’ll use a spectrophotometer to measure how much light the hair transmits or reflects (faded dye won’t reflect as much light). “We’re hoping this will tell us whether hair makes a good dye go bad — if a lightfast dye becomes a non-lightfast dye due to hair interaction,” Ritchie says.

After that, the conservators plan to spray dye onto bison hair, stick those samples into the chamber, and then use a Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy machine to see if the dye degrades the hair.

By the time the project wraps up next fall, the team hopes to have collected enough data to inform the creation of a set of openly accessible best practices for retreating mammal taxidermy in museums in the future.

“We’re coming up with ways of representing what we’ve found — different visual representations of how to ‘rank the dyes’” based on how lightfast they are, Ritchie says. In the next year, the team will host a workshop on retreating mammal hair, designed for museum professionals and other conservators who care for historic taxidermy.

It’s possible that these standards might become a sort of protocol for recoloring and retreatment practices for natural history museums as well as art institutions, says Ritchie.

“There’s very little published information about this, and so we’re really hoping to contribute to the field of art conservation in general through this project,” Ritchie says. “You really need to know how materials will degrade over time, how they’ll interact with each other over time, and what can be the most stable so that you don’t risk harming your precious object by something that you did to it.”

This story was first published by Science Friday with Ira Flatow.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!