An immigrant family remembers the past and ponders their future under Trump

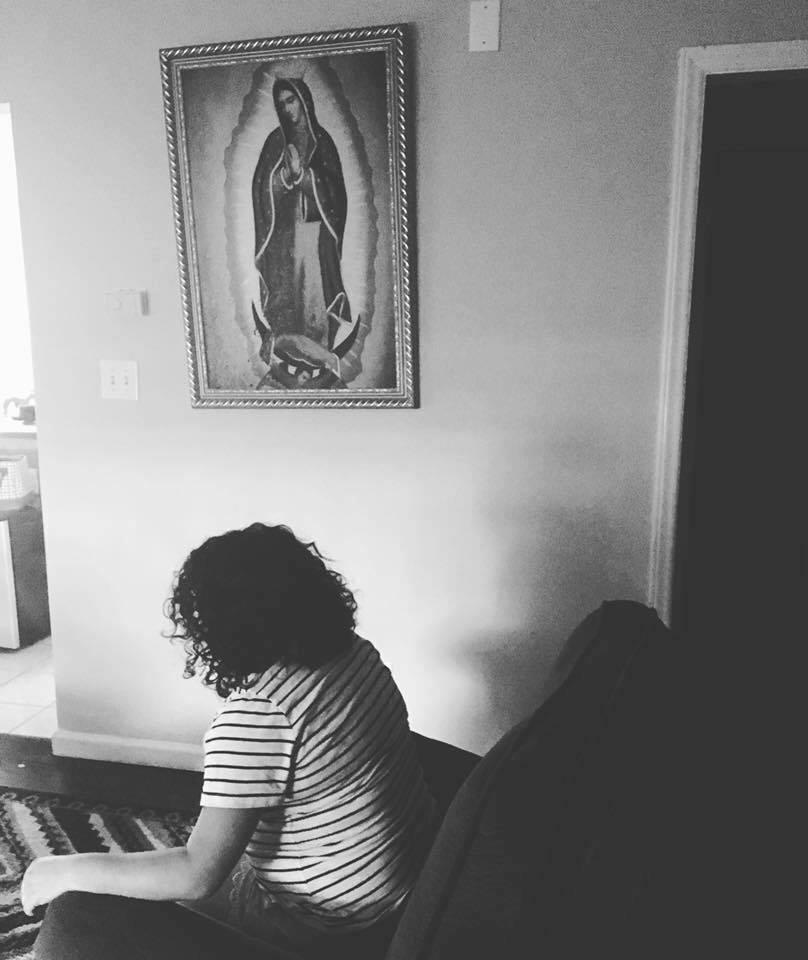

Despite being undocumented, Zully was able to go to college to study arts. Much of her work reflects her experience as an immigrant in America.

Some stories shouldn’t be told.

That's a lesson Zully learned in third grade. They were studying airplanes and she told her teacher she’d never flown in one — and how her mom carried her from Mexico to North Carolina.

"My mom literally walked the desert, a 17-year-old, carrying her 2-year-old daughter. She says she … got thorns stuck in her shoes, but she couldn't stop. And she says she got to the point where all we had left to drink was one Coke bottle. So she says she saved it for me. Because she'd rather I drink it than her. And then it suddenly hit me." Zully, who didn't want to be identified by her full name because of her uncertain status, thinks back to her teacher's perplexed look. "I don't think I should be telling her this."

That was 15 years ago. Now — she's no longer scared of telling her story as we sit on her porch. It’s quiet. The suburbs. While Zully talks, she gets goosebumps. But she says she’s not cold. "Part of me feels like I am home," she continues. "But then there's this part that tells me: but this isn't your home."

There are hundreds of thousands of people like Zully, who grew up undocumented in America — with no memories from their native country. Her parents are also undocumented. It was around high school when she realized what this meant for her. No driver’s license. No work permit. No college. Zully says she became despondent.

Her life changed in 2012 when the Obama administration created a program called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals — DACA. It temporarily protects people like Zully from deportation. About 740,000 immigrants have enrolled in the program so far. For Zully, it means being able to drive and work legally, and study fine arts. She'd like to get her master's degree, and become an art therapist. But, now, she's not sure she can. President-elect Donald Trump promised to get tough on immigration — and get rid of DACA. It’s making Zully rethink her place in America, whether or not this is home.

"It's not my home because I can't do certain things people can do. I want to be able to vote. But I can't vote," she says.

Her reflections get cut short by the school bus and the arrival of her younger sister, who is 9.

Of her three siblings, Zully’s the only one without legal status. The only one not born here. As she helps with homework, she tells me how, on the night of the election, her little sister started saying she didn’t want her parents to get sent back to Mexico. "My mom was telling her, everything is going to be OK. Nothing is going to happen. But if it does, we're a family, as long as we're together, it's OK. You can do anything you want, anywhere in the world."

But not everyone in North Carolina was afraid after the election. Conrad Pogorzelksi leads the College Republicans at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte. "On election night, I was just stoked. It was just incredible to see."

He says immigration reform — getting rid of programs like DACA — is needed. "I understand it's not an easy thing to talk about. I understand most of these people are coming here for a better life. But I think it is something that needs to be addressed. You have to have rules in place."

He hopes Trump enforces those rules — and it’s looking like he will. "When it finally happened, when we knew Trump was going to work, I turned to my buddy and said, 'Welcome to a new America.'"

What this new America means for Zully's family is unclear.

Zully's mother, Maria, arrives later in the evening. She cleans houses for a living. One of the ladies she works for voted for Trump. "And I think to myself. If you build that wall, and take us all out, who's going to come clean your dirty house. I doubt white people like you."

Maria feels she’s needed in this economy. President-elect Trump talks tough, but he’s hardly the first to promise an immigration crackdown. President Barack Obama has deported more people than any other US leader. And after more than 20 years, Maria is still here.

Zully is less sure about the future. She does know she’ll put up a fight if the Trump administration takes away her legal status. But … she’s also tired.

"I've gotten to the point where I don't care if I leave. I want to be somewhere I can call home. And do all these things. Oh I don't know."

Her mother, Maria, tells her it's going to be OK. They've faced difficult times before. Just the two of them. "I always tell her, I gave you the last Coca-Cola. It was the last thing we had, and I wanted you to have it. I always wanted her to have what I didn't."

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!