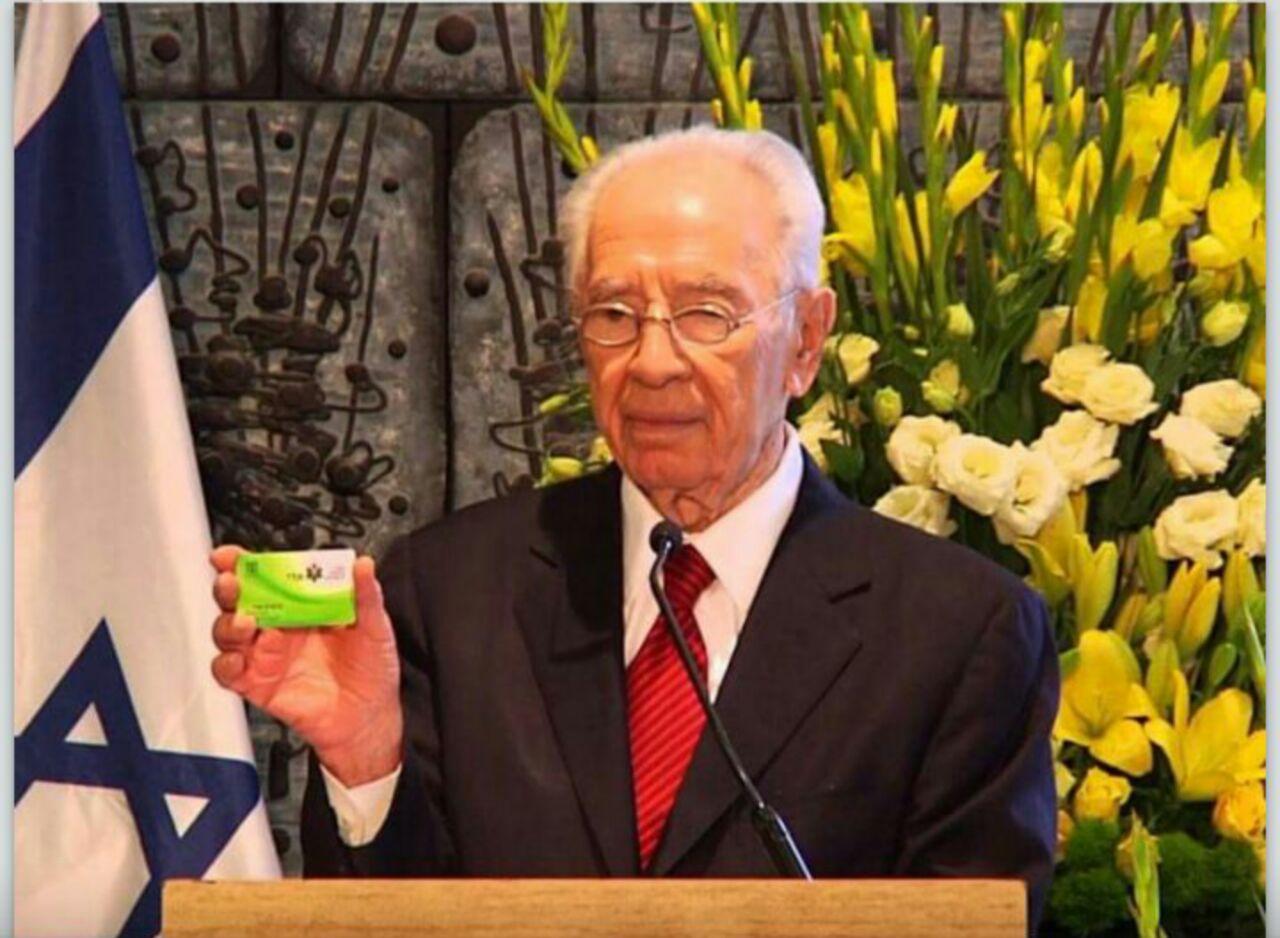

Shimon Peres was a proud holder of an Israeli organ donor card.

When Shimon Peres was Israel’s president in 2012, he gathered families of organ donors at his residence in Jerusalem and pulled out a green plastic card. It was from the National Transplant Center, Adi in Hebrew.

He told them that he had signed up to be an organ donor and that the Adi card was one of the most important documents in his life. He urged other Israelis to sign up, too.

And this past week, when he died at the age of 93, his corneas were donated.

Only about 15 percent of Israelis have signed up as organ donors, compared to about 45 percent of Americans who have organ donor cards. Organ donation rates are even higher in some European countries.

That all drives Robby Berman crazy — especially since many Israelis are secular Jews who don’t follow religious rules.

“They [have] tattoos which is forbidden by the Bible. They [eat] cheeseburgers which is forbidden by the Bible,” says Berman, who’s Israeli American. “Yet when it came to donating organs, they said no they couldn’t because it contradicted Jewish law.”

Berman runs the Halachic Organ Donor Society in Jerusalem. That first word, Halachic, refers to Jewish law based on the Talmud. And that’s Berman’s strategy: to convince Jews in Israel and abroad that Judaism allows them to donate their organs.

But here’s what he’s up against: First, what is death?

“There are rabbis who believe that when the person’s brain is dead … they believe a person is alive. They believe a pumping heart signifies life,” Berman says. “The chief rabbinate of Israel ruled 20 years ago that a brain death is death, and people should donate organs, but the masses are unaware of that.”

There are also laws in the Bible.

“You’re not allowed to mutilate or desecrate a dead body. You’re not allowed to delay burial of a dead body, and you’re not allowed to get benefit from a dead body, so you couldn’t sell a dead body to [a] medical school and get money for it,” he says. “But all rabbis agree that if you can save a life you’re supposed to override almost every biblical commandment.”

Another challenge: Some religious Jews believe they’ll need their organs when they’re resurrected.

How could Shimon Peres donating his corneas compete with that?

“That’s not going to change my mind. If I believe I need my organs for the resurrection of the dead, so fine, Shimon Peres was an idiot. He’ll be resurrected from the dead but he’ll be blind. That’s what they’re thinking. He’ll be blind,” Berman says.

When I tell Berman that I’m surprised by his pessimism, he sets out to prove his point. We stop some passersby in Jerusalem, including Ilan Marmor, a bank manager. He emigrated from France 35 years ago. Berman asks if he has a donor card, and Marmor says no.

“May I ask why you don’t have?” Berman asks.

“I don’t know,” Marmor says. “It’s very useful for society that people should donate but nobody has asked me.”

We also stop a young woman who says her name is Liat. And she tells us she’s not an organ donor because she’s religious.

So Berman starts listing rabbis who support organ donations: Chief Rabbi Shlomo Amar and the late chief rabbis Ovadia Yosef and Mordechai Eliyahu.

Maybe I’ll sign up, Liat concedes.

Organ donation in Israel has gone up since Berman started his group. Fifteen years ago, only three percent of Israelis had a donor card, compared with the 15 percent today.

As for Palestinians, they don’t have an organ donor program, but they’re working on it, according to a spokesman for the Palestinian Ministry of Health.

Earlier this year, Meir Dagan, the former chief of the Mossad, Israel’s intelligence agency, died and donated his corneas. An elderly blind man received one of them, which restored his vision. A woman in her 70s received the other.

And now someone else in Israel will receive one or both of Shimon Peres’s corneas.

Emanuel Saunders, a 29-year-old Israeli artist who signed up to be a donor a few years ago, says it seemed like a small way to possibly save a life. Now, he thinks about what it might be like for the person who gets the corneas from Shimon Peres, who was celebrated for his sunny outlook.

“To receive optimistic eyes, I don’t think it’s a bad thing,” Saunders says.