President Barack Obama was born in Hawaii and raised for a few years as a child in Indonesia. A statue of him as a 10-year-old stood outside his former school, State Elementary School 01 Menteng, in Jakarta. This image was taken on November 7, 2012.

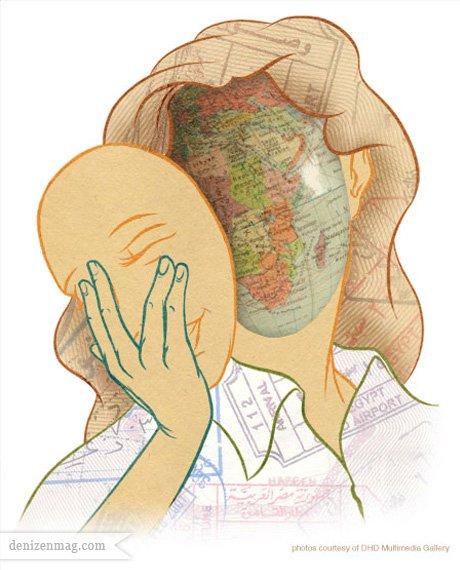

The fast-approaching presidential election also means the final months in office for the country’s first African American president. Barack Obama, though, is also part of a distinct cultural group that we don't talk about as often: TCKs, or "third culture kids."

They’re usually kids of missionaries or military members, or more recently, kids of employees of international companies. They spend formative years in countries other than the home countries of their parents, sometimes in international American schools. So they’re an unusual combination of cultures, hence the term "third culture kid."

"Every October, during Halloween, it becomes a huge deal in that neighborhood," Yiu recalls. "And so there would be people who would come to Little America just to experience trick-or-treating and Halloween. It’s not too dissimilar with like how people might go to Chinatown to experience Chinese New Year right?”

So Yiu sounds American and grew up doing a lot of the things that American kids do — she went to school dances. So she knew how the US worked when she went to college at Northwestern University in Illinois. But she had weird cultural knowledge gaps compared to American students.

“In many ways, I function as sort of an invisible immigrant, which a lot of of TCKs do," Yiu says. "They show up in college and they’re an invisible immigrant. They walk around, they might look American, they sound American, and they’re just expected to blend in and figure it out. But you haven’t watched the same TV shows as everybody or experienced the same cultural things as everybody. And they may not know that you’re different but you are. You just kind of roll with it. You just figure it out.”

Yiu’s not complaining. She says the TCK upbringing can be really priviledged. But people who grow up that way are a really particular blend of cultures with unique insight into the ways different traditions intersect. They get to a point where they don’t expect other people to understand them. Yiu says her background is so confusing to people that when she’s at parties and people ask her where she’s from, she lies.

"If someone asks me where am I from, I will sort of dance around the truth a bit. Because it takes so darn long to explain it," she says. "Not that I’m trying to be deceitful. It’s just that it’s so complicated. When I’m in Hong Kong, which is where I was born and where my family is from, I don’t really fit in there. I’m Asian so I look like I’m from Hong Kong, but I certainly don’t sound like I’m from Hong Kong. So I’ll just be like, ‘Oh I’m from Singapore.’”

Yiu changes what she says about herself based on who she's speaking to. It's a life of constant re-adjustment, which she's grown used to and accepted, as other TCKs have. The third culture experience, she says, made them really complex people, gave them unique insight and taught them to be comfortable in multiple cultures.

And that's why, at the end of Obama's presidency, it's interesting to note that for the past eight years, there's been a TCK in charge.

Subscribe to Otherhood on iTunes and find host Rupa Shenoy on Twitter @RupaShenoy.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!