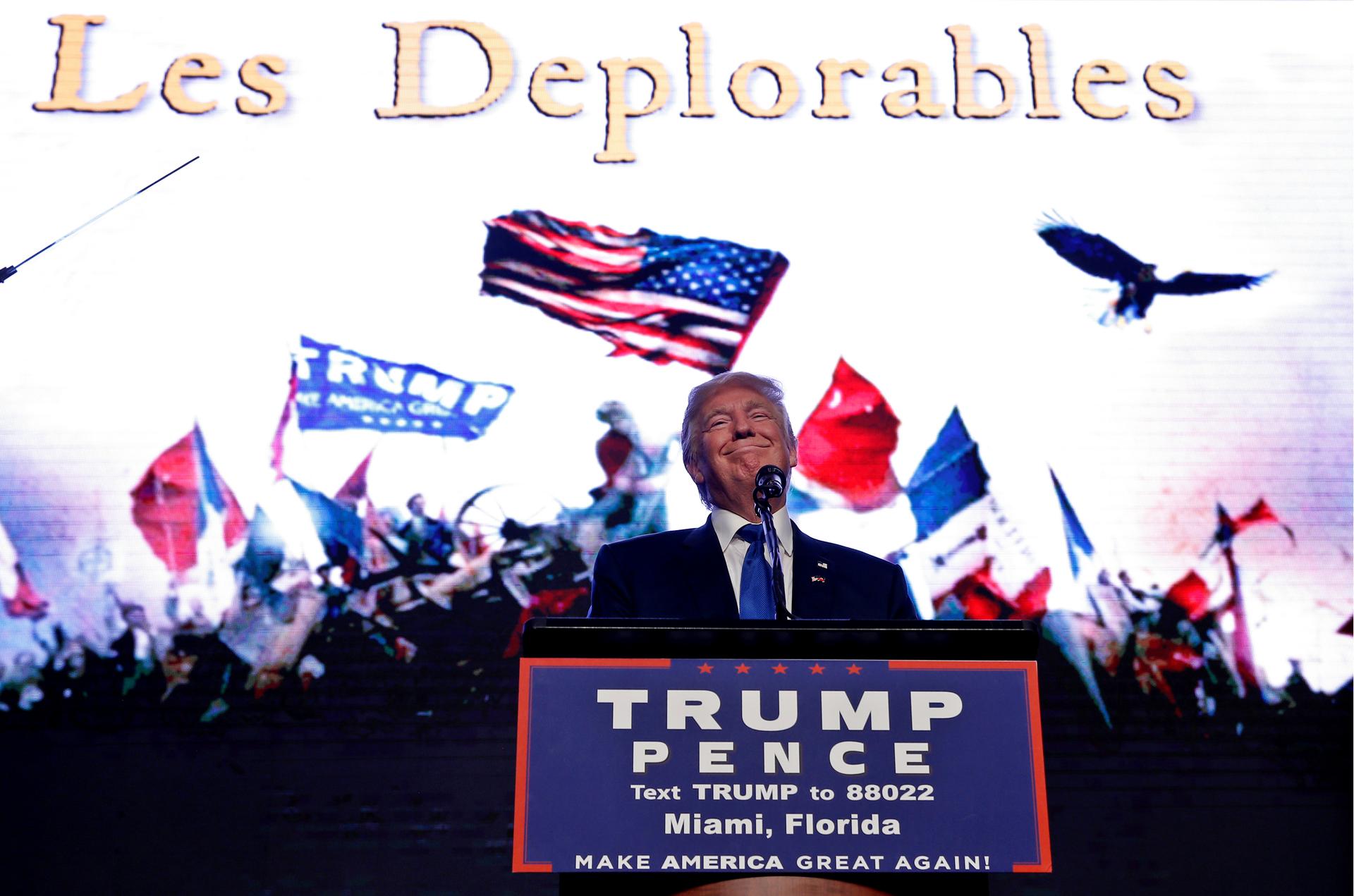

Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump appears at a campaign rally in Miami, Florida, US, September 16, 2016.

The filters are off this election season. And honestly, a lot of the talk is terrible to hear.

Hate speech feels commonplace at rallies.

And many critics of presidential candidate Donald Trump say his blunt — some would use worse adjectives — talk is to blame. But is his speech actually worse than usual?

It's difficult to quantify, but that's what Cleveland Plain Dealer chief political reporter Henry Gomez set out to do.

He looked at the number of racist comments lobbed his way prior to this election. And then he compared the comments to the ones coming his way this election. Gomez says the number of hateful emails and calls increased, significantly.

I have heard their voice mails and read their emails. Smirked at their keyboard courage in the comments section. Told myself not to take the Twitter mentions too personally.

Call it bigotry. Call it racism. Call it xenophobia. As a writer – especially one who covers national politics – you chalk it up as coming with the territory, as hurtful and as menacing as it can be. This year, though, it is coming far more frequently. There is no mystery why.

Maybe you don't believe Donald Trump is a bigot. Or a racist. Or a xenophobe. But the Republican nominee for president certainly has won the support of people who are.

He points to Trump's campaign as being a cause for many of the emails he's received.

"They'd be isolated here or there in the past. In 2012, when I covered the [Mitt] Romney and [Barack] Obama campaigns, I could probably count on one hand the number of offensive emails or voicemails that I received from readers. And here, we're talking in the dozens."

And sometimes, those emails target him because of his last name — but they might be disappointed when they meet him.

"I was born in Youngstown, Ohio. My parents were born in Youngstown, Ohio. I think you have to go back four generations to find someone in our family who was born in another country. My father's relatives descended from Mexico. My mother is Italian, Irish and German. So I'm a third-generation American," he says. "I don't speak Spanish. My sister got the tan genes in our family and I got my mother's paler complexion."

Gomez says, before the comments, he never really had to deal with racism directed at him because of his last name.

"I grew up in a very typical Midwest suburb of Youngstown. I wouldn't call it enlightened," he says. "But I didn't really deal with racism growing up. I never was made fun of because of my last name. This was just something that was unheard of back then and now it seems to have become en vogue."

But through it all, he hasn't given up hope for the future.

"I'm hopeful that people will start realizing that this is wrong," he says. "That there is a right and wrong and that treating people, or pre-judging people, because of their last names or their ethnicities or cultural identities is plain wrong."

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?