Mapping the Milky Way as never before

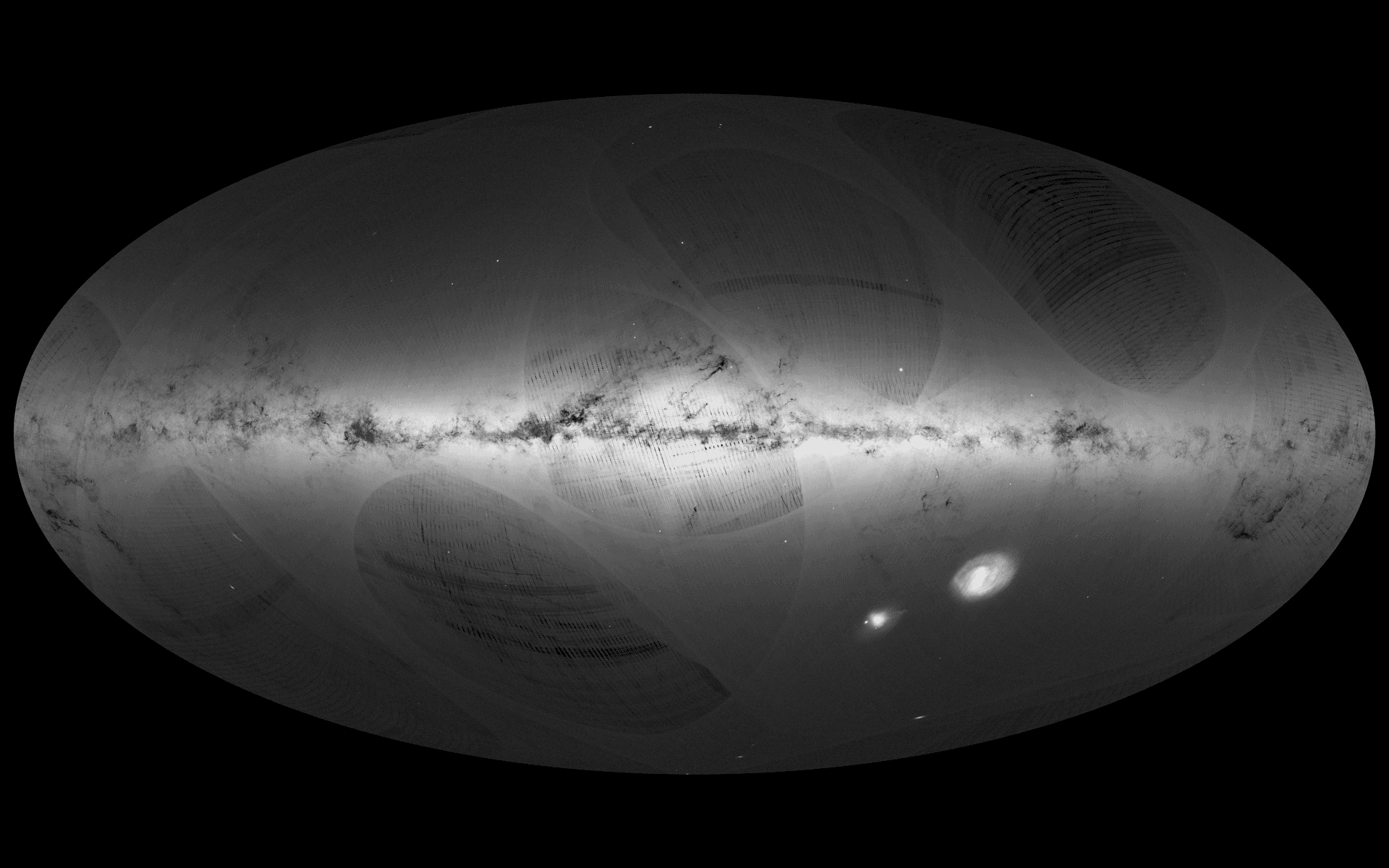

This map shows an all-sky view of stars the Milky Way and neighbouring galaxies, based on the first year of observations from ESA’s Gaia satellite, from July 2014 to September 2015.

The Gaia space probe, launched in 2013, has mapped more than a billion stars in the Milky Way, vastly expanding the inventory of known stars in our galaxy, the European Space Agency said Wednesday.

Released to eagerly waiting astronomers around the world, the initial catalogue of 1.15 billion stars is "both the largest and the most accurate full-sky map ever produced," said Francois Mignard, a member of the 450-strong Gaia mission team.

In a webcast press conference at ESA's Astronomy Centre in Madrid, scientists unveiled a stunning map of the Milky Way, including stars up to half a million times less bright than those we can see with the naked eye.

The images were captured by Gaia's twin telescopes — scanning the heavens over and over — and a billion-pixel camera, the biggest ever put into space.

The resolution is sharp enough to gauge the diameter of a human hair at a distance of 620 miles, says Anthony Brown, a researcher at Leiden University in the Netherlands and a member of Gaia's data processing and analysis team.

He compared the images to those captured by NASA's $2.5-billion Hubble Space Telescope, which has recorded some of the most detailed visible-light photographs of space, one section at a time.

"Imagine taking pictures with Hubble, except of the full sky — that is effectively what you are seeing here," Brown says.

Gaia maps the position of stars in the Milky Way, which straddles some 100,000 light years, in two ways.

Not only does it pinpoint their location, the probe — by scanning each star multiple times — plots their movement as well.

Wednesday's map showed the locations of over a billion stars, a bonanza for astronomers but still only one percent our galaxy's estimated stellar population.

For two million of them, it also shows their trajectory.

Over the course of Gaia's five-year mission, the catalogue of stars for which both sets of data are known is set to expand 500-fold.

At the same time, it will collect vital data on temperature, luminosity and chemical composition, compiling what astronomers call the "ID card" of each individual star.

Thousands of other previously undetected objects have also been discovered, including asteroids that may one day threaten Earth, planets circling nearby stars, and exploding supernovas.

'How was our galaxy formed?'

Astrophysicists, meanwhile, hope to learn more about dark matter, the invisible substance thought to hold the observable universe together.

They also plan to test Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity by watching how light is deflected by the sun and its planets.

"There is a new revolution coming," says Antonella Vallenari of Italy's National Institute for Astrophysics, and a member of the Gaia team.

"Gaia is meant to answer a fundamental question: How was our galaxy formed?"

Tracking star clusters and how they move through space — shedding stars along the way — will provide crucial clues, she adds.

"Stars remember that they were built together, and continue to move together in a single direction," she says.

This makes it possible to pick out "lone stars" that only appear to be grouped with others.

Some 2,500 such clusters — the incubators of new stars — have been identified in the Milky Way so far, but scientists suspect there are upwards of 100,000.

Gaia should be able to track down all of them.

Orbiting the sun nearly a million miles beyond Earth's orbit, the European probe started collecting data in July 2014.

A first batch of scientific studies based on the new data — made available to scientists beforehand — was published Wednesday in a special edition of the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Today's release "opens a new chapter in astronomy," Mignard said, and is certain to generate hundreds more studies.