A new book looks at the life, history and legacy of Patient H.M.

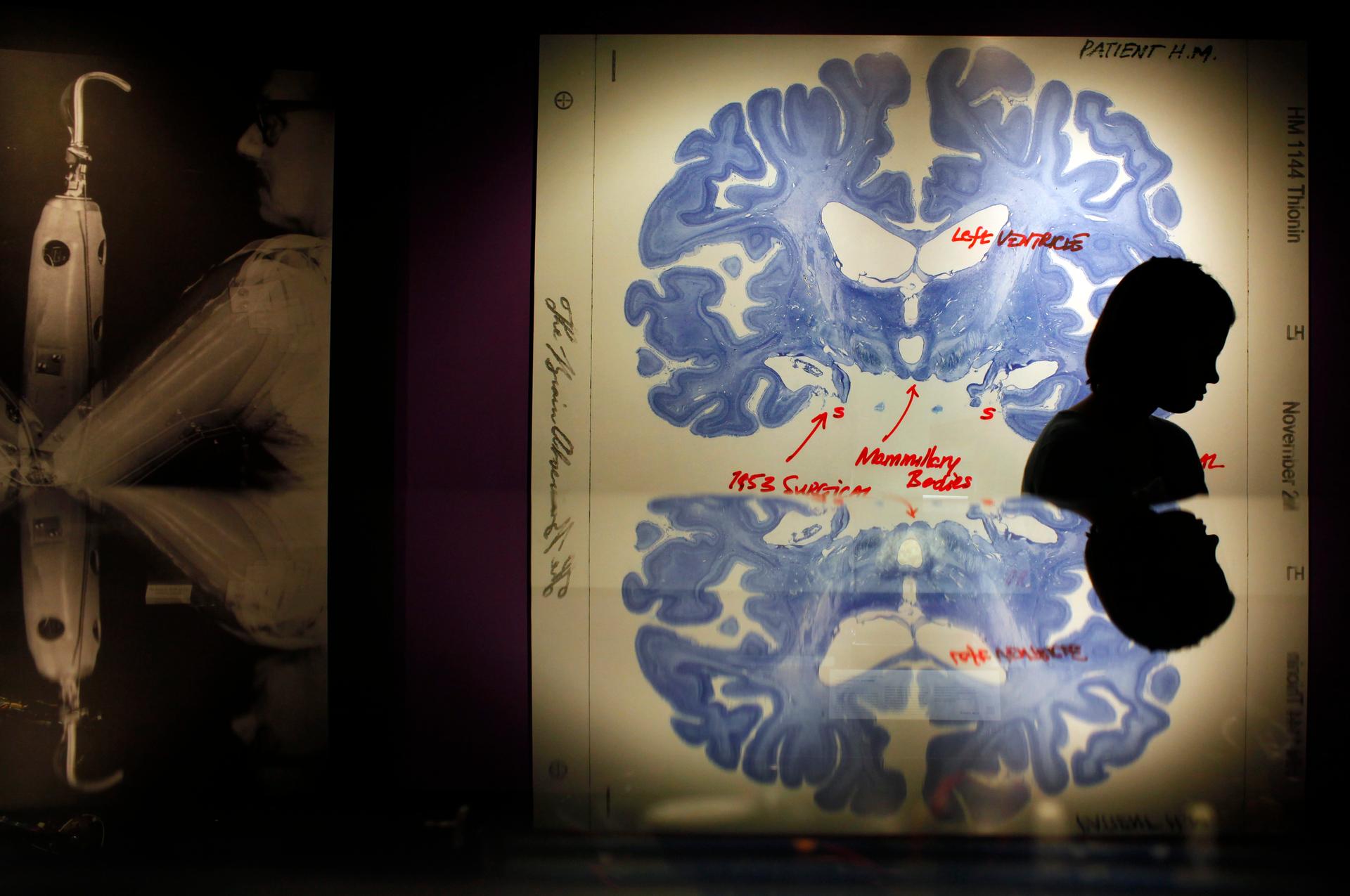

A woman walks past a display of a brain slice of patient "H.M." at the 150 Exhibition at the MIT Museum, celebrating Massachusetts Institute of Technology's 150th anniversary, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Patient H.M. has been extensively studied because of his inability to form long term memories following brain surgery in 1953 for his epilepsy.

In 1953, during experimental brain surgery aimed at curing his epilepsy, doctors removed several key portion’s of Henry Molaison’s brain. The operation left him in a persistent amnesiac state.

For the next four decades, neuroscientists conducted study after study on Molaison to determine the extent of the damage, and he became one of the most famous cases in neuroscience for his contributions to our understanding of memory.

When Molaison died in 2008, his brain was sliced thin and digitized by a team at UC San Diego, to be studied in depth — leading to one of the more bizarre scientific ownership battles in recent history.

Journalist Luke Dittrich has written a new book, Patient H.M: A Story of Memory, Madness and Family Secrets, examining the details of Molaison’s life as a patient, research subject and man, and how his story fits into the era of lobotomies and other highly experimental human brain surgeries.

As it happens, Dittrich has a unique perspective on the events: His grandfather was the surgeon who removed the critical parts of Henry Molaison’s brain, transforming him into the anonymous Patient H.M.

“When I began working on this book, it quickly became clear that there was an entire chunk of my family history that I was entirely unaware of, that also had strange implications for memory science,” Dittrich says. “My grandmother was mentally ill and she was institutionalized in the 1940s. My grandfather became, in part as a result of her mental illness, a very passionate practitioner of and advocate for psychosurgery, which is what we usually think of as the lobotomy.”

Lobotomy is a surgical treatment that was based on the belief that doctors could treat all sorts of mental illness by removing certain parts of the brain. The technique was inspired by research performed on chimpanzees at Yale University.

Scientists lesioned the frontal lobes of these animals and found that, when faced with difficult tasks afterwards, they couldn't perform them as well as they had before the operation. But even more intriguingly, the chimps no longer got as upset when they failed to execute the tasks properly. They exhibited less so-called "experimental neurosis."

A Portuguese neurologist named Egas Moniz wondered whether humans with lesioned frontal lobes would also exhibit less neurosis or would be less anxious or troubled. He began performing the first lobotomies on humans in the late 1930s. The idea quickly crossed the Atlantic Ocean and an American neurologist named Walter Freeman began performing a variation of Moniz’s lobotomy. Others, like Dittrich’s grandfather, refined the procedure further.

“I was constantly struck by how this was not a fringe procedure,” Dittrich says. “This was embraced … and pushed not just by doctors and researchers, but by the mass media. The New York Times was running articles about the lobotomy and talking about how suddenly it was as easy to remove madness as it was to pluck a diseased tooth. There was a lot of general mainstream excitement about this.”

During his research, Dittrich came to believe that it was impossible to understand the case of Patient H.M. without understanding this campaign of psychosurgical experimentation that his grandfather had participated in.

This was an era when modern notions of informed consent really didn't exist, Dittrich points out. John Fulton, a prominent scientist at Yale University, encouraged a fellow researcher to spend time with Dr. Scoville — Dittrich’s grandfather — because Scoville had been given “unlimited access to the psychiatric material of [his] institution.”

“I had to read it twice before I realized ‘psychiatric material’ meant human beings,” Dittrich says. “That sort of attitude, the blurring of the lines between medical research and medical practice, was prevalent at the time.”

H.M.’s operation, even though it wasn’t, strictly speaking, a psychosurgical procedure, was identical to a procedure known as orbital under-cutting, which Scoville had developed in the asylums, and had then decided to see whether it could be modified or adapted as a treatment for epilepsy, Dittrich explains.

Using this procedure, Scoville levered up Molaison’s frontal lobes, probed deeper into the region known as the medial temporal lobe, and removed most of his patient’s hippocampus, amygdala, uncus and entorhinal cortex.

“At the time, nobody knew exactly what these brain structures did, which doesn't excuse it, because you would think maybe it's best not to remove them,” Dittrich says. “My grandfather hoped that this operation would alleviate Molaison’s seizures; H.M. did suffer from devastating epilepsy. In a sense, there was this, once again, strange straddling of the divide between medical practice and medical research.”

For Molaison, the results were catastrophic. From that moment forward, he lived the rest of his life in, basically, 30-second increments. “The present would just sort of slide off of him constantly,” Dittrich says.

From a scientific perspective, the operation was revelatory. Dr Scoville had been performing similar operations on psychotic patients in the back wards of asylums, but their minds were so muddied by mental illness that the actual effect of the operation was difficult to glean, Dittrich explains. Apart from his epilepsy, Molaison was psychologically sound, so it became immediately apparent what he had lost after the operation, whereas it hadn't been so apparent in the asylum patients.

In 1955, Dr. Scoville and a neuropsychologist at McGill University named Brenda Milner collaborated on a paper centered on H.M. that became “the cornerstone for the skyscraper that is modern memory science,” Dittrich says.

“It had a very simple, but revolutionary conclusion: that Henry clearly could no longer create new long-term memories,” Dittrich says. “They knew, more or less, exactly what had been taken from his brain, and so they knew those structures must be required to create new long-term memories — and that was a revelation.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Science Friday with Ira Flatow.

In 1953, during experimental brain surgery aimed at curing his epilepsy, doctors removed several key portion’s of Henry Molaison’s brain. The operation left him in a persistent amnesiac state.

For the next four decades, neuroscientists conducted study after study on Molaison to determine the extent of the damage, and he became one of the most famous cases in neuroscience for his contributions to our understanding of memory.

When Molaison died in 2008, his brain was sliced thin and digitized by a team at UC San Diego, to be studied in depth — leading to one of the more bizarre scientific ownership battles in recent history.

Journalist Luke Dittrich has written a new book, Patient H.M: A Story of Memory, Madness and Family Secrets, examining the details of Molaison’s life as a patient, research subject and man, and how his story fits into the era of lobotomies and other highly experimental human brain surgeries.

As it happens, Dittrich has a unique perspective on the events: His grandfather was the surgeon who removed the critical parts of Henry Molaison’s brain, transforming him into the anonymous Patient H.M.

“When I began working on this book, it quickly became clear that there was an entire chunk of my family history that I was entirely unaware of, that also had strange implications for memory science,” Dittrich says. “My grandmother was mentally ill and she was institutionalized in the 1940s. My grandfather became, in part as a result of her mental illness, a very passionate practitioner of and advocate for psychosurgery, which is what we usually think of as the lobotomy.”

Lobotomy is a surgical treatment that was based on the belief that doctors could treat all sorts of mental illness by removing certain parts of the brain. The technique was inspired by research performed on chimpanzees at Yale University.

Scientists lesioned the frontal lobes of these animals and found that, when faced with difficult tasks afterwards, they couldn't perform them as well as they had before the operation. But even more intriguingly, the chimps no longer got as upset when they failed to execute the tasks properly. They exhibited less so-called "experimental neurosis."

A Portuguese neurologist named Egas Moniz wondered whether humans with lesioned frontal lobes would also exhibit less neurosis or would be less anxious or troubled. He began performing the first lobotomies on humans in the late 1930s. The idea quickly crossed the Atlantic Ocean and an American neurologist named Walter Freeman began performing a variation of Moniz’s lobotomy. Others, like Dittrich’s grandfather, refined the procedure further.

“I was constantly struck by how this was not a fringe procedure,” Dittrich says. “This was embraced … and pushed not just by doctors and researchers, but by the mass media. The New York Times was running articles about the lobotomy and talking about how suddenly it was as easy to remove madness as it was to pluck a diseased tooth. There was a lot of general mainstream excitement about this.”

During his research, Dittrich came to believe that it was impossible to understand the case of Patient H.M. without understanding this campaign of psychosurgical experimentation that his grandfather had participated in.

This was an era when modern notions of informed consent really didn't exist, Dittrich points out. John Fulton, a prominent scientist at Yale University, encouraged a fellow researcher to spend time with Dr. Scoville — Dittrich’s grandfather — because Scoville had been given “unlimited access to the psychiatric material of [his] institution.”

“I had to read it twice before I realized ‘psychiatric material’ meant human beings,” Dittrich says. “That sort of attitude, the blurring of the lines between medical research and medical practice, was prevalent at the time.”

H.M.’s operation, even though it wasn’t, strictly speaking, a psychosurgical procedure, was identical to a procedure known as orbital under-cutting, which Scoville had developed in the asylums, and had then decided to see whether it could be modified or adapted as a treatment for epilepsy, Dittrich explains.

Using this procedure, Scoville levered up Molaison’s frontal lobes, probed deeper into the region known as the medial temporal lobe, and removed most of his patient’s hippocampus, amygdala, uncus and entorhinal cortex.

“At the time, nobody knew exactly what these brain structures did, which doesn't excuse it, because you would think maybe it's best not to remove them,” Dittrich says. “My grandfather hoped that this operation would alleviate Molaison’s seizures; H.M. did suffer from devastating epilepsy. In a sense, there was this, once again, strange straddling of the divide between medical practice and medical research.”

For Molaison, the results were catastrophic. From that moment forward, he lived the rest of his life in, basically, 30-second increments. “The present would just sort of slide off of him constantly,” Dittrich says.

From a scientific perspective, the operation was revelatory. Dr Scoville had been performing similar operations on psychotic patients in the back wards of asylums, but their minds were so muddied by mental illness that the actual effect of the operation was difficult to glean, Dittrich explains. Apart from his epilepsy, Molaison was psychologically sound, so it became immediately apparent what he had lost after the operation, whereas it hadn't been so apparent in the asylum patients.

In 1955, Dr. Scoville and a neuropsychologist at McGill University named Brenda Milner collaborated on a paper centered on H.M. that became “the cornerstone for the skyscraper that is modern memory science,” Dittrich says.

“It had a very simple, but revolutionary conclusion: that Henry clearly could no longer create new long-term memories,” Dittrich says. “They knew, more or less, exactly what had been taken from his brain, and so they knew those structures must be required to create new long-term memories — and that was a revelation.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI’s Science Friday with Ira Flatow.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!