I’m a professor in Texas and I’m worried about students who can now carry guns in my class

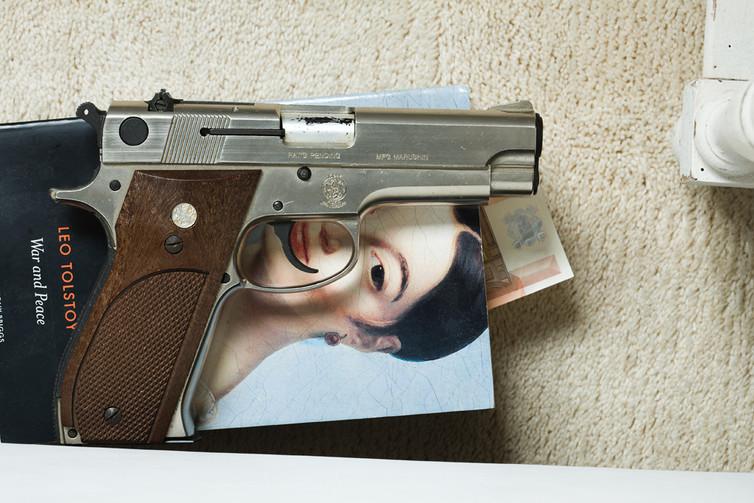

War, peace and guns on campus: Will guns on campus allow critical thinking?

As of Aug. 1, a new law allows concealed handguns in college and university buildings in Texas.

It’s already had an impact on me as professor of religious studies at the University of Texas at Austin. Thanks to this law, I set foot in a federal court building for the first time.

And I was not alone. The courtroom was packed. Other citizens were there as well to support three professors who are suing the state’s attorney general and the University of Texas for the right to ban guns from their own classrooms.

Why are these professors taking the extraordinary step of suing the state of Texas and their own university?

In order to understand the situation, we need to consider the political tensions between the legislature and the university, the ideological struggle over the goals of higher education and the possible dangers of bringing more guns to campuses.

Campus carry law in Texas

Until this year, Texas law allowed anyone with a Concealed Handgun License to carry a loaded hidden gun on campus, but not inside buildings. This restriction kept down the number of people carrying weapons legally on campus.

During the 2015 legislative session, a majority of Republicans pushed the idea to allow guns on campus. University administrators, faculty, faculty council, staff, undergraduate and graduate students and campus police overwhelmingly opposed the idea.

However, in spite of campus opposition, in May 2015, the proposed law, known as Senate Bill 11 (SB 11), was approved. So, as of Aug. 1, anyone with a concealed handgun license can carry a loaded, semiautomatic pistol into most offices, classrooms, hallways, public spaces, cafeterias and gyms at state universities. All that they need: four hours of training and a score of 70 percent accuracy on a shooting test.

Supporters argue that Americans have a constitutional right to protect themselves and carry weapons with as few limits as possible. Carrying guns into classrooms, they say, is part of that right.

Clash of ideologies

For many of us, however, this conflict is about a larger ideological battle over the goals and character of higher education in Texas, with one side emphasizing obedience to authority and the other the need to critique authority.

Let’s consider these two views of education.

The ideology of higher education in the U.S. has historically focused on critical thinking, and faculty overwhelmingly see this as the primary goal (see especially Table 3) of college and university classes. According to this view, universities and colleges are encouraged to question orthodoxy. In other words, higher education should subject all truth claims to intense scrutiny.

The goal of this process is not to tear down society but to make it better, to allow us to develop our full potential as individuals and as a nation in the pursuit of liberty and justice.

But here is where the conflict comes in. As the discussion below shows, the campus carry movement has, it seems, a different ideology for higher education. The underlying motivation is that traditional authority must be maintained and, in the end, disagreement is resolved by force, not by debate. For this ideology, critical thinking is a potential threat to authority.

Republican Party principles

Evidence for this comes from the ideas expressed in the Texas Republican Party platform, a formal declaration of the principles on which a party stands and makes it appeal to voters.

The 2012 Texas Republican Party Platform took an explicit stand against “critical thinking skills and similar programs…that focus on behavior modification and have the purpose of challenging the student’s fixed beliefs and undermining parental authority.”

Subsequently, the 2016 Texas Republican Platform stepped back from that extreme statement. But it still asserted that parents or guardians — not the government — should have ultimate control over the education of their children.

In the 2016 platform, both guns and religion are discussed in the section on education. Here is what it looks like:

The section on education supports the radical position that all law-abiding citizens should be able to carry guns anywhere without restriction. It says,

“We collectively urge the legislature to pass ‘constitutional carry’ legislation, whereby law-abiding citizens that possess firearms can legally exercise their God-given right to carry that firearm as well. We call for the elimination of all gun free zones. All federal acts, laws, executive orders, and court orders which restrict or infringe on the people’s right to keep and bear arms shall be invalid in Texas, not be recognized by Texas, shall be specifically rejected by Texas, and shall be considered null and void and of no effect in Texas.”

Another paragraph in the education section discusses “safeguarding religious liberties.“ This one begins by saying,

“We affirm that the public acknowledgment of God is undeniable in our history and is vital to our freedom, prosperity, and strength.”

It goes on to denounce “the myth of separation of church and state,” and it supports the right of businesses to refuse service to anyone based on religious conviction.

What this does is to reaffirm the ideology of the Republican Party of Texas — that education should be governed by traditional authorities of family and conservative forms of Protestant Christianity and not by critical inquiry.

In other words, religious commitment of individuals is more important than civil rights. Furthermore, according to this traditionalist view of authority, liberty and safety are preserved not so much by critique and analysis as by encouraging everyone to carry a gun.

Views from ground zero

This raises the question of how this ideology affects students and professors in the classroom.

As the political battle raged in the Texas legislature in spring 2016, I taught a science and religion class in which we spent the semester analyzing the volatile debates in the U.S. about human evolution and creationism.

I asked my students how they would feel about the possible presence of guns in classrooms.

One student self-identified as having a concealed handgun license and did not have trouble with the presence of guns. But most others thought that it would make them more cautious and less forthright in class. One student said she would be vigilant about how other students were acting. Another said she would censor her opinions.

The sentiment they expressed was confirmed in anonymous polling I conducted before our discussion. Two students (11 percent) were in favor of concealed carry on campus as demanded by SB 11, while 13 (68 percent) thought guns should be completely illegal on campus except for law officers. Only three students (16 percent) felt that SB 11 would make them safer, while 11 (58 percent) expected that the law would make campus less safe.

While one class is hardly a representative sample, these numbers reflect discussions I’ve had with my classes over the last few semesters. The numbers also match a variety of conversations I’ve had on campus.

What might change on campus?

As a professor, I have other concerns for my students beyond the classroom. We work with students at a difficult time in their lives as they work through the transition to adulthood. Some of them also face serious emotional issues. When I have to deal with failed exams, missed assignments and occasional plagiarism or cheating, I sometimes worry about how they will respond.

So far I have not encountered physical threats to my own safety, but I know faculty who have. While waiting in line for the security screening at the federal courthouse, I learned of two more examples. One was a professor of computer sciences who told me about the time when he was physically shoved and verbally abused by a student who got a B rather than an A.

He decided not to press charges. But when the legislature passed the campus carry law, he retired rather than face the possibility of legal weapons in university buildings. Another faculty member told of the time she had to persuade her dean to drop a student from her class midsemester for anti-Semitic remarks the student made about her.

Systematic studies point toward other problems that await us if we increase the number of guns on campus. We can expect more accidental shootings, more successful suicide attempts and perhaps even an increase in sexual assaults. In the event of an actual active shooter event, we can expect that an armed civilian will make no difference or even make the situation worse.

Will guns change the character of higher education?

The ideological struggle will continue. Polling early in 2015 showed that Texans were divided on campus carry: 47 percent were in favor, 45 percent were opposed and 8 percent were unsure (this included 22 percent strongly supporting and 32 percent strongly opposed). Campus protests and a satirical student campaign against SB 11 are planned.

Supporters of the law have filed a formal complaint with the attorney general’s office to make the law stronger by preventing faculty and staff from banning guns in their own offices. Legal papers filed by the University of Texas and the state attorney general have stated that professors would face disciplinary measures if they barred guns from classrooms. There is significant political pressure and special interest money to expand gun rights.

If the lawsuit of the three professors is not successful, we will begin to find out fairly soon what difference SB 11 will actually make in real lives — in the classroom, in the relationships of students, faculty and staff — and in the character of higher education in an American setting.

The actual difference will not be abstract or theoretical. Both opponents and supporters of SB 11 claim that the struggle over guns on campus is a matter of life and death.

![]()

Steven J. Friesen, Professor, Louise Farmer Boyer Chair in Biblical Studies, University of Texas at Austin

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

As of Aug. 1, a new law allows concealed handguns in college and university buildings in Texas.

It’s already had an impact on me as professor of religious studies at the University of Texas at Austin. Thanks to this law, I set foot in a federal court building for the first time.

And I was not alone. The courtroom was packed. Other citizens were there as well to support three professors who are suing the state’s attorney general and the University of Texas for the right to ban guns from their own classrooms.

Why are these professors taking the extraordinary step of suing the state of Texas and their own university?

In order to understand the situation, we need to consider the political tensions between the legislature and the university, the ideological struggle over the goals of higher education and the possible dangers of bringing more guns to campuses.

Campus carry law in Texas

Until this year, Texas law allowed anyone with a Concealed Handgun License to carry a loaded hidden gun on campus, but not inside buildings. This restriction kept down the number of people carrying weapons legally on campus.

During the 2015 legislative session, a majority of Republicans pushed the idea to allow guns on campus. University administrators, faculty, faculty council, staff, undergraduate and graduate students and campus police overwhelmingly opposed the idea.

However, in spite of campus opposition, in May 2015, the proposed law, known as Senate Bill 11 (SB 11), was approved. So, as of Aug. 1, anyone with a concealed handgun license can carry a loaded, semiautomatic pistol into most offices, classrooms, hallways, public spaces, cafeterias and gyms at state universities. All that they need: four hours of training and a score of 70 percent accuracy on a shooting test.

Supporters argue that Americans have a constitutional right to protect themselves and carry weapons with as few limits as possible. Carrying guns into classrooms, they say, is part of that right.

Clash of ideologies

For many of us, however, this conflict is about a larger ideological battle over the goals and character of higher education in Texas, with one side emphasizing obedience to authority and the other the need to critique authority.

Let’s consider these two views of education.

The ideology of higher education in the U.S. has historically focused on critical thinking, and faculty overwhelmingly see this as the primary goal (see especially Table 3) of college and university classes. According to this view, universities and colleges are encouraged to question orthodoxy. In other words, higher education should subject all truth claims to intense scrutiny.

The goal of this process is not to tear down society but to make it better, to allow us to develop our full potential as individuals and as a nation in the pursuit of liberty and justice.

But here is where the conflict comes in. As the discussion below shows, the campus carry movement has, it seems, a different ideology for higher education. The underlying motivation is that traditional authority must be maintained and, in the end, disagreement is resolved by force, not by debate. For this ideology, critical thinking is a potential threat to authority.

Republican Party principles

Evidence for this comes from the ideas expressed in the Texas Republican Party platform, a formal declaration of the principles on which a party stands and makes it appeal to voters.

The 2012 Texas Republican Party Platform took an explicit stand against “critical thinking skills and similar programs…that focus on behavior modification and have the purpose of challenging the student’s fixed beliefs and undermining parental authority.”

Subsequently, the 2016 Texas Republican Platform stepped back from that extreme statement. But it still asserted that parents or guardians — not the government — should have ultimate control over the education of their children.

In the 2016 platform, both guns and religion are discussed in the section on education. Here is what it looks like:

The section on education supports the radical position that all law-abiding citizens should be able to carry guns anywhere without restriction. It says,

“We collectively urge the legislature to pass ‘constitutional carry’ legislation, whereby law-abiding citizens that possess firearms can legally exercise their God-given right to carry that firearm as well. We call for the elimination of all gun free zones. All federal acts, laws, executive orders, and court orders which restrict or infringe on the people’s right to keep and bear arms shall be invalid in Texas, not be recognized by Texas, shall be specifically rejected by Texas, and shall be considered null and void and of no effect in Texas.”

Another paragraph in the education section discusses “safeguarding religious liberties.“ This one begins by saying,

“We affirm that the public acknowledgment of God is undeniable in our history and is vital to our freedom, prosperity, and strength.”

It goes on to denounce “the myth of separation of church and state,” and it supports the right of businesses to refuse service to anyone based on religious conviction.

What this does is to reaffirm the ideology of the Republican Party of Texas — that education should be governed by traditional authorities of family and conservative forms of Protestant Christianity and not by critical inquiry.

In other words, religious commitment of individuals is more important than civil rights. Furthermore, according to this traditionalist view of authority, liberty and safety are preserved not so much by critique and analysis as by encouraging everyone to carry a gun.

Views from ground zero

This raises the question of how this ideology affects students and professors in the classroom.

As the political battle raged in the Texas legislature in spring 2016, I taught a science and religion class in which we spent the semester analyzing the volatile debates in the U.S. about human evolution and creationism.

I asked my students how they would feel about the possible presence of guns in classrooms.

One student self-identified as having a concealed handgun license and did not have trouble with the presence of guns. But most others thought that it would make them more cautious and less forthright in class. One student said she would be vigilant about how other students were acting. Another said she would censor her opinions.

The sentiment they expressed was confirmed in anonymous polling I conducted before our discussion. Two students (11 percent) were in favor of concealed carry on campus as demanded by SB 11, while 13 (68 percent) thought guns should be completely illegal on campus except for law officers. Only three students (16 percent) felt that SB 11 would make them safer, while 11 (58 percent) expected that the law would make campus less safe.

While one class is hardly a representative sample, these numbers reflect discussions I’ve had with my classes over the last few semesters. The numbers also match a variety of conversations I’ve had on campus.

What might change on campus?

As a professor, I have other concerns for my students beyond the classroom. We work with students at a difficult time in their lives as they work through the transition to adulthood. Some of them also face serious emotional issues. When I have to deal with failed exams, missed assignments and occasional plagiarism or cheating, I sometimes worry about how they will respond.

So far I have not encountered physical threats to my own safety, but I know faculty who have. While waiting in line for the security screening at the federal courthouse, I learned of two more examples. One was a professor of computer sciences who told me about the time when he was physically shoved and verbally abused by a student who got a B rather than an A.

He decided not to press charges. But when the legislature passed the campus carry law, he retired rather than face the possibility of legal weapons in university buildings. Another faculty member told of the time she had to persuade her dean to drop a student from her class midsemester for anti-Semitic remarks the student made about her.

Systematic studies point toward other problems that await us if we increase the number of guns on campus. We can expect more accidental shootings, more successful suicide attempts and perhaps even an increase in sexual assaults. In the event of an actual active shooter event, we can expect that an armed civilian will make no difference or even make the situation worse.

Will guns change the character of higher education?

The ideological struggle will continue. Polling early in 2015 showed that Texans were divided on campus carry: 47 percent were in favor, 45 percent were opposed and 8 percent were unsure (this included 22 percent strongly supporting and 32 percent strongly opposed). Campus protests and a satirical student campaign against SB 11 are planned.

Supporters of the law have filed a formal complaint with the attorney general’s office to make the law stronger by preventing faculty and staff from banning guns in their own offices. Legal papers filed by the University of Texas and the state attorney general have stated that professors would face disciplinary measures if they barred guns from classrooms. There is significant political pressure and special interest money to expand gun rights.

If the lawsuit of the three professors is not successful, we will begin to find out fairly soon what difference SB 11 will actually make in real lives — in the classroom, in the relationships of students, faculty and staff — and in the character of higher education in an American setting.

The actual difference will not be abstract or theoretical. Both opponents and supporters of SB 11 claim that the struggle over guns on campus is a matter of life and death.

![]()

Steven J. Friesen, Professor, Louise Farmer Boyer Chair in Biblical Studies, University of Texas at Austin

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

At The World, we believe strongly that human-centered journalism is at the heart of an informed public and a strong democracy. We see democracy and journalism as two sides of the same coin. If you care about one, it is imperative to care about the other.

Every day, our nonprofit newsroom seeks to inform and empower listeners and hold the powerful accountable. Neither would be possible without the support of listeners like you. If you believe in our work, will you give today? We need your help now more than ever!