Meet a renowned astronomer who is still searching for ET, 50 years later

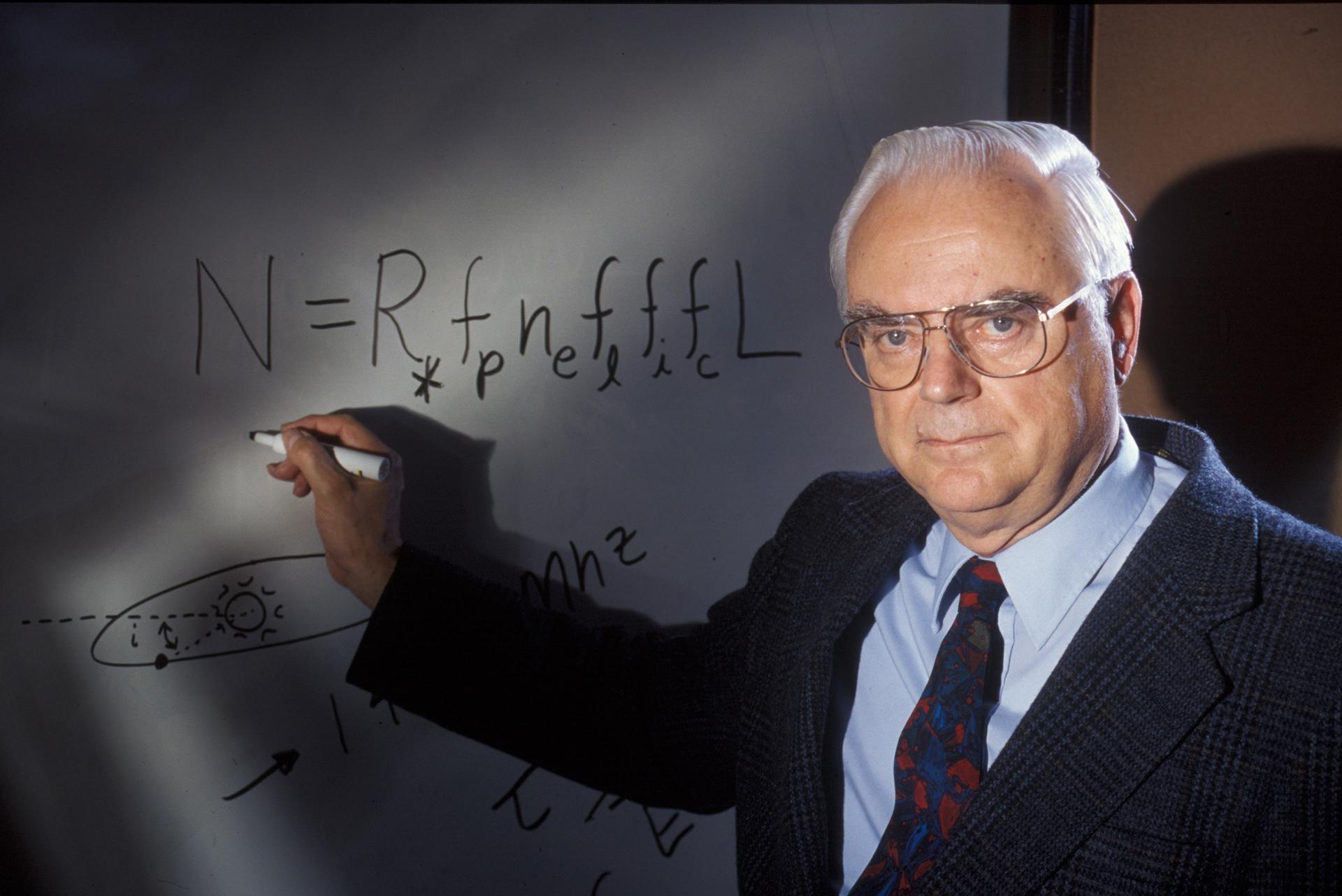

Frank Drake with his Drake Equation.

When astronomer Frank Drake organized the first SETI (search for extraterrestrial intelligence) conference back in 1961 in Green Bank, West Virginia, only a dozen people attended.

“I invited everyone in the world I knew about who was interested in the subject or who had written something about it — so all 12,” Drake remembers fondly. “All [were] very enthusiastic, because they’d all been in a situation I’d been in — that they were very interested in this subject, but it was taboo. They really couldn’t pursue or even talk about it, so it was just a joy to be with other people who were as eager as they were.”

It was at this meeting that Drake introduced what became known as the Drake equation, a formula intended to estimate the number of intelligent and communicative civilizations in the Milky Way. Drake claims he had “no idea” how much of an impact it would have on people’s conceptions of the possibility of intelligent life beyond Earth.

Indeed, much has changed in the 55 years since that first conference.

“Now I go to giant meetings where [SETI’s] the main subject. I walk in a room and see 300 people sitting there,” Drake says. “Here are all these really talented people, and they’re now all working on this same thing and don’t feel like it’s a bad thing at all.”

Drake, 86, is still passionate about the hunt for extraterrestrial life. He’s currently participating in Breakthrough Initiatives, a new program backed by entrepreneur Yuri Milner that’s searching for interstellar life through radio and optical signals. And thanks to the recent findings of more exoplanets and more possibilities of Earth-like worlds, Drake says he remains optimistic that we’ll find something out there.

Science Friday recently spoke with Drake about how he got interested in extraterrestrials, misconceptions about SETI, and what excites him about the future.

How did you first get interested in the idea of extraterrestrial life?

I was a little 8-year-old kid living in Chicago, and my father one day told me there are other worlds in space, which astounded me. I had no idea that such a thing was a possibility—I thought Earth was it. It was a medieval attitude. So that just really catalyzed me, and I wondered, Oh, what are they like? Are the people the same as us, do they look the same way we do? What’s their planet like? And of course, at that time, there was no way those questions could be answered in the slightest.

Later on, I was very interested in engineering, and when I was in college, I took a required general science course. I chose the elementary astronomy course. While I was taking that course, we went to the local campus observatory, and one of the things we observed was the planet Jupiter. Even through a small telescope, it is just very clear that you’re seeing another world, that it’s different from ours, that it’s got colors and clouds, and it’s got four moons. And I looked at that and thought, This is real. These aren’t pictures in a book or something. There really are things like that out there. And that converted me.

Did you have any major influences, people who inspired you?

There were two people that were running the [astronomy] program at Harvard [where Drake earned both a master’s and a Ph.D.]. One was a traditional astronomer named Bart Bok. He’s famous in astronomy for being one of the great students of the structure of the Milky Way galaxy. He was a very enthusiastic scientist, and his enthusiasm rubbed off on all the students, including myself.

But there was a second person who was sort of a wild man. His name was Doc Ewen. He had gotten a Ph.D. at Harvard in physics, during which he discovered this famous thing in astronomy: the radio emission line from the hydrogen atom, which allowed us to observe hydrogen all through the universe, and is very central in astronomical work to this day. He had done that by building a small radio telescope all by himself and sticking it out a window, actually at the physics building at Harvard University. He was the technical leader in the teaching of the graduate students at Harvard, and he was just an amazing person. He was brilliant and extremely active and energetic and willing to try anything, and he acted as a good model for people who wondered whether it was really a good idea to be daring. He showed you could be daring and succeed, and if you fail, that’s all right — you could try again.

In 1960, you launched the experiment called Project Ozma, the first attempt to search for signs of extraterrestrial life through interstellar radio waves. How did that come about?

When I finished at Harvard, I took one of the first positions at a new observatory being built in West Virginia, which was to be a major national observatory to provide radio astronomy facilities to Americans. This was 1958. The first thing we did there was to build what was to us a big telescope, but it really wasn’t — it was an 85-foot-telescope. Still there today. That was very exciting to build that and put it into operation.

One of the first things that came to my mind was, could this telescope be used to detect other civilizations? So I did the calculations as to how far away a civilization could be that was sending out radio signals at the same level we were at that time, and we could detect the signals. It turned out to be about 10 light years. Well, that got interesting. If it had been a tenth of a light year, we would have had to say forget it, there’re no stars within that distance. But within 10 light years, there are almost a dozen stars. It was not a crazy idea to search for radio signals from those nearby stars, because if any of them were just like us—it didn’t have to be a super civilization, just another civilization using no better technology than we had—then we could find them. And of course, this was exciting, because to me, finding another world is something I’d wanted to do all my life at that point.

Fortunately, the director there at that time [named Otto Struve] was one of the world’s most eminent astronomers, and he was actually a great believer in extraterrestrial life, so he was very enthusiastic about me doing this project, and he said go right ahead. So I did.

Did you otherwise receive a lot of criticism for trying to search for extraterrestrial life?

No, people humored me. When I did [Project Ozma], there were a few protests, because we did use a few hundred hours of telescope time at Green Bank in West Virginia, and a few people said that’s not a good use of the taxpayers’ money. But it cost so little — the equipment cost $2,000. If it had been a million-dollar project, I think there would have been an outcry. As time has gone on, all the criticisms have gone away. [SETI]’s now considered a very legitimate subject to pursue.

Soon after Project Ozma, you introduced the Drake Equation at the SETI meeting. Were you nervous when you presented it?

No, because I didn’t think it was a big deal. That’s the thing that totally amazes me now is that I see it everywhere. People send me photographs of where they’ve had it tattooed on their arms. One guy has it tattooed across his forehead. When I give lectures, about one in five times, somebody comes up to me and shows me where the tattoo is on their arm or their leg.

It [the equation] came about because I was running the three-day meeting, and I realized we should put down kind of an agenda. So I thought about what things needed to be discussed, what was important. The goal of the meeting was to get a feel for how difficult the search was going to be, and how we should search. So I just asked myself: What is important in understanding how many detectable civilizations would be out there? I realized there were seven factors involved, such as how many habitable planets there are, how often life arises and how often it evolves intelligence, and how many intelligent creatures have the technology that we can detect across interstellar distances. Out of the factors, to this day, the really difficult one is: How long do they remain detectable? I realized, well this is neat, I can use these factors as the subject for a morning discussion, then an afternoon discussion with a different factor, and so on, and go through all seven in three days. So I wrote them all down, and I realized—what you do is just multiply them all together, and what you get is what we’re after, which is the number of [intelligent and communicative] civilizations in the galaxy.

What do you imagine when you think about extraterrestrials? What do they look like?

I can imagine some forms. I’m sure there are places where the planetary circumstances were such that they would not favor an anatomy or physiology like ours, where the creatures would be very different. It could be carbon-based life, but it could be something like an octopus. An octopus is very different from us but yet has a very large brain and acts almost like an intelligent creature if you fool around with them. Dolphins are another example of a life form that is nearly as intelligent as us but is different. When I was an 8-year-old kid, I thought they would all just be like us; they’d be indistinguishable. What we know now is that nowhere will there be duplicates of us.

But then, on the other hand — and this is my own thinking about this — we are a good design, because we are optimized for the place we live in. We evolved into a life form that can exist and prosper in a place with temperatures we have now; access to bodies of water; access to plants for food; and, as a predator, to creatures that we can capture and eat. And so, where there are planets much like Earth — with bodies of water but also solid surface available, and where plants thrive — I think we may find creatures that are a lot like us, because we are a good design. We stand upright, which frees our forelimbs to manipulate tools and to build structures and use technology. Having a head with eyes on top is a good thing, because it’s easier to see predators, to see over the grass where the danger is and where you should go to find the food. So, my image of what a lot of the extraterrestrials would look like is what I just described to you—a creature like us.

What are the biggest misconceptions about SETI?

Well, one of them is that we have searched and failed. People say that all the time: ‘You’ve been searching for 60 years, and you haven’t found anything, so doesn’t that say that intelligent life is very rare?’ But that’s wrong, because the amount of searching that we’ve done has hardly touched the number of possibilities that are out there — that is, stars and radio frequencies and channels and all of that. We’ve only covered a tiny, tiny fraction of all the possibilities.

Another one, which unfortunately doesn’t seem to die, is that the evolution of intelligence is very rare. This is one that is held by some very senior paleontologists. The argument is that in the history of the earth, there have been something like hundreds of thousands of species of animal, and only one became intelligent, and doesn’t that mean that the chance of intelligence is 1 in hundreds of thousands? That of course kind of sounds good, but it’s a specious argument, because what we know from evolution is that the complexity of living creatures continuously increases with time—they have more abilities, they get larger brains, and that’s well-documented. And eventually, because intelligence is a very valuable trait, you’ll get an intelligent creature. [Drake defines “intelligence” in this context as the brainpower and understanding to develop high-power technology such as radio transmitters.]

What happens is, species don’t all evolve at the same rate, so not every species becomes intelligent at once. Given a longer time, some other creatures will become intelligent, which will probably happen on Earth unless we prevent it, which we’ve been good at doing.

What might be the next best ‘candidate’ on Earth for gaining intelligence?

There’s an obvious one, the chimpanzees. Or the bonobo — that’s the closest thing in physiology and social life to humans, so the bonobos are the prime candidate for our successor, if we ever wipe ourselves out or allow ourselves to be wiped out. If the planet gave them a million years to evolve, they would become us.

Another creature I always cite, which is half-joke and half-serious, is squirrels. If you look at the fossil record, our own most ancient ancestor 65 million years ago was a small mammal that was almost like a squirrel; it was the same size, it ran on four legs on the ground. And then 65 million years later, that became us. Squirrels are very smart—they can get at any bird feeder; you can’t hide food from them; they stand on their rear legs and their front paws as hands to manipulate things just the way we do; and they’re always watching us. You can see they’re saying, ‘Just give me time, I’m going to take over.’

What is your favorite accomplishment so far?

Well, just getting the search started [with Project Ozma]. Demonstrating that it could be done, and that it was reasonable and it didn’t require anything special [that is, extraterrestrial life doesn’t necessarily have to be more advanced or staring us in the face for us to find it]. There have been about 100 SETI projects in the last 56 years, and now they’ve been superseded by the Breakthrough Initiative Project. So all that grew out of that one-channel search 56 years ago.

What do you still want to accomplish?

I just want to find ’em! If we could find one, that would be terrific. Once you find one, you can figure out how to build a telescope that would actually allow you to find out what they’re like and learn about them. Of course, that would be a huge turning point for our whole civilization. To have access to all that information from another world would just be life-altering for everybody on Earth, I think.

This story was first published by Science Friday with Ira Flatow.

When astronomer Frank Drake organized the first SETI (search for extraterrestrial intelligence) conference back in 1961 in Green Bank, West Virginia, only a dozen people attended.

“I invited everyone in the world I knew about who was interested in the subject or who had written something about it — so all 12,” Drake remembers fondly. “All [were] very enthusiastic, because they’d all been in a situation I’d been in — that they were very interested in this subject, but it was taboo. They really couldn’t pursue or even talk about it, so it was just a joy to be with other people who were as eager as they were.”

It was at this meeting that Drake introduced what became known as the Drake equation, a formula intended to estimate the number of intelligent and communicative civilizations in the Milky Way. Drake claims he had “no idea” how much of an impact it would have on people’s conceptions of the possibility of intelligent life beyond Earth.

Indeed, much has changed in the 55 years since that first conference.

“Now I go to giant meetings where [SETI’s] the main subject. I walk in a room and see 300 people sitting there,” Drake says. “Here are all these really talented people, and they’re now all working on this same thing and don’t feel like it’s a bad thing at all.”

Drake, 86, is still passionate about the hunt for extraterrestrial life. He’s currently participating in Breakthrough Initiatives, a new program backed by entrepreneur Yuri Milner that’s searching for interstellar life through radio and optical signals. And thanks to the recent findings of more exoplanets and more possibilities of Earth-like worlds, Drake says he remains optimistic that we’ll find something out there.

Science Friday recently spoke with Drake about how he got interested in extraterrestrials, misconceptions about SETI, and what excites him about the future.

How did you first get interested in the idea of extraterrestrial life?

I was a little 8-year-old kid living in Chicago, and my father one day told me there are other worlds in space, which astounded me. I had no idea that such a thing was a possibility—I thought Earth was it. It was a medieval attitude. So that just really catalyzed me, and I wondered, Oh, what are they like? Are the people the same as us, do they look the same way we do? What’s their planet like? And of course, at that time, there was no way those questions could be answered in the slightest.

Later on, I was very interested in engineering, and when I was in college, I took a required general science course. I chose the elementary astronomy course. While I was taking that course, we went to the local campus observatory, and one of the things we observed was the planet Jupiter. Even through a small telescope, it is just very clear that you’re seeing another world, that it’s different from ours, that it’s got colors and clouds, and it’s got four moons. And I looked at that and thought, This is real. These aren’t pictures in a book or something. There really are things like that out there. And that converted me.

Did you have any major influences, people who inspired you?

There were two people that were running the [astronomy] program at Harvard [where Drake earned both a master’s and a Ph.D.]. One was a traditional astronomer named Bart Bok. He’s famous in astronomy for being one of the great students of the structure of the Milky Way galaxy. He was a very enthusiastic scientist, and his enthusiasm rubbed off on all the students, including myself.

But there was a second person who was sort of a wild man. His name was Doc Ewen. He had gotten a Ph.D. at Harvard in physics, during which he discovered this famous thing in astronomy: the radio emission line from the hydrogen atom, which allowed us to observe hydrogen all through the universe, and is very central in astronomical work to this day. He had done that by building a small radio telescope all by himself and sticking it out a window, actually at the physics building at Harvard University. He was the technical leader in the teaching of the graduate students at Harvard, and he was just an amazing person. He was brilliant and extremely active and energetic and willing to try anything, and he acted as a good model for people who wondered whether it was really a good idea to be daring. He showed you could be daring and succeed, and if you fail, that’s all right — you could try again.

In 1960, you launched the experiment called Project Ozma, the first attempt to search for signs of extraterrestrial life through interstellar radio waves. How did that come about?

When I finished at Harvard, I took one of the first positions at a new observatory being built in West Virginia, which was to be a major national observatory to provide radio astronomy facilities to Americans. This was 1958. The first thing we did there was to build what was to us a big telescope, but it really wasn’t — it was an 85-foot-telescope. Still there today. That was very exciting to build that and put it into operation.

One of the first things that came to my mind was, could this telescope be used to detect other civilizations? So I did the calculations as to how far away a civilization could be that was sending out radio signals at the same level we were at that time, and we could detect the signals. It turned out to be about 10 light years. Well, that got interesting. If it had been a tenth of a light year, we would have had to say forget it, there’re no stars within that distance. But within 10 light years, there are almost a dozen stars. It was not a crazy idea to search for radio signals from those nearby stars, because if any of them were just like us—it didn’t have to be a super civilization, just another civilization using no better technology than we had—then we could find them. And of course, this was exciting, because to me, finding another world is something I’d wanted to do all my life at that point.

Fortunately, the director there at that time [named Otto Struve] was one of the world’s most eminent astronomers, and he was actually a great believer in extraterrestrial life, so he was very enthusiastic about me doing this project, and he said go right ahead. So I did.

Did you otherwise receive a lot of criticism for trying to search for extraterrestrial life?

No, people humored me. When I did [Project Ozma], there were a few protests, because we did use a few hundred hours of telescope time at Green Bank in West Virginia, and a few people said that’s not a good use of the taxpayers’ money. But it cost so little — the equipment cost $2,000. If it had been a million-dollar project, I think there would have been an outcry. As time has gone on, all the criticisms have gone away. [SETI]’s now considered a very legitimate subject to pursue.

Soon after Project Ozma, you introduced the Drake Equation at the SETI meeting. Were you nervous when you presented it?

No, because I didn’t think it was a big deal. That’s the thing that totally amazes me now is that I see it everywhere. People send me photographs of where they’ve had it tattooed on their arms. One guy has it tattooed across his forehead. When I give lectures, about one in five times, somebody comes up to me and shows me where the tattoo is on their arm or their leg.

It [the equation] came about because I was running the three-day meeting, and I realized we should put down kind of an agenda. So I thought about what things needed to be discussed, what was important. The goal of the meeting was to get a feel for how difficult the search was going to be, and how we should search. So I just asked myself: What is important in understanding how many detectable civilizations would be out there? I realized there were seven factors involved, such as how many habitable planets there are, how often life arises and how often it evolves intelligence, and how many intelligent creatures have the technology that we can detect across interstellar distances. Out of the factors, to this day, the really difficult one is: How long do they remain detectable? I realized, well this is neat, I can use these factors as the subject for a morning discussion, then an afternoon discussion with a different factor, and so on, and go through all seven in three days. So I wrote them all down, and I realized—what you do is just multiply them all together, and what you get is what we’re after, which is the number of [intelligent and communicative] civilizations in the galaxy.

What do you imagine when you think about extraterrestrials? What do they look like?

I can imagine some forms. I’m sure there are places where the planetary circumstances were such that they would not favor an anatomy or physiology like ours, where the creatures would be very different. It could be carbon-based life, but it could be something like an octopus. An octopus is very different from us but yet has a very large brain and acts almost like an intelligent creature if you fool around with them. Dolphins are another example of a life form that is nearly as intelligent as us but is different. When I was an 8-year-old kid, I thought they would all just be like us; they’d be indistinguishable. What we know now is that nowhere will there be duplicates of us.

But then, on the other hand — and this is my own thinking about this — we are a good design, because we are optimized for the place we live in. We evolved into a life form that can exist and prosper in a place with temperatures we have now; access to bodies of water; access to plants for food; and, as a predator, to creatures that we can capture and eat. And so, where there are planets much like Earth — with bodies of water but also solid surface available, and where plants thrive — I think we may find creatures that are a lot like us, because we are a good design. We stand upright, which frees our forelimbs to manipulate tools and to build structures and use technology. Having a head with eyes on top is a good thing, because it’s easier to see predators, to see over the grass where the danger is and where you should go to find the food. So, my image of what a lot of the extraterrestrials would look like is what I just described to you—a creature like us.

What are the biggest misconceptions about SETI?

Well, one of them is that we have searched and failed. People say that all the time: ‘You’ve been searching for 60 years, and you haven’t found anything, so doesn’t that say that intelligent life is very rare?’ But that’s wrong, because the amount of searching that we’ve done has hardly touched the number of possibilities that are out there — that is, stars and radio frequencies and channels and all of that. We’ve only covered a tiny, tiny fraction of all the possibilities.

Another one, which unfortunately doesn’t seem to die, is that the evolution of intelligence is very rare. This is one that is held by some very senior paleontologists. The argument is that in the history of the earth, there have been something like hundreds of thousands of species of animal, and only one became intelligent, and doesn’t that mean that the chance of intelligence is 1 in hundreds of thousands? That of course kind of sounds good, but it’s a specious argument, because what we know from evolution is that the complexity of living creatures continuously increases with time—they have more abilities, they get larger brains, and that’s well-documented. And eventually, because intelligence is a very valuable trait, you’ll get an intelligent creature. [Drake defines “intelligence” in this context as the brainpower and understanding to develop high-power technology such as radio transmitters.]

What happens is, species don’t all evolve at the same rate, so not every species becomes intelligent at once. Given a longer time, some other creatures will become intelligent, which will probably happen on Earth unless we prevent it, which we’ve been good at doing.

What might be the next best ‘candidate’ on Earth for gaining intelligence?

There’s an obvious one, the chimpanzees. Or the bonobo — that’s the closest thing in physiology and social life to humans, so the bonobos are the prime candidate for our successor, if we ever wipe ourselves out or allow ourselves to be wiped out. If the planet gave them a million years to evolve, they would become us.

Another creature I always cite, which is half-joke and half-serious, is squirrels. If you look at the fossil record, our own most ancient ancestor 65 million years ago was a small mammal that was almost like a squirrel; it was the same size, it ran on four legs on the ground. And then 65 million years later, that became us. Squirrels are very smart—they can get at any bird feeder; you can’t hide food from them; they stand on their rear legs and their front paws as hands to manipulate things just the way we do; and they’re always watching us. You can see they’re saying, ‘Just give me time, I’m going to take over.’

What is your favorite accomplishment so far?

Well, just getting the search started [with Project Ozma]. Demonstrating that it could be done, and that it was reasonable and it didn’t require anything special [that is, extraterrestrial life doesn’t necessarily have to be more advanced or staring us in the face for us to find it]. There have been about 100 SETI projects in the last 56 years, and now they’ve been superseded by the Breakthrough Initiative Project. So all that grew out of that one-channel search 56 years ago.

What do you still want to accomplish?

I just want to find ’em! If we could find one, that would be terrific. Once you find one, you can figure out how to build a telescope that would actually allow you to find out what they’re like and learn about them. Of course, that would be a huge turning point for our whole civilization. To have access to all that information from another world would just be life-altering for everybody on Earth, I think.

This story was first published by Science Friday with Ira Flatow.

The World is an independent newsroom. We’re not funded by billionaires; instead, we rely on readers and listeners like you. As a listener, you’re a crucial part of our team and our global community. Your support is vital to running our nonprofit newsroom, and we can’t do this work without you. Will you support The World with a gift today? Donations made between now and Dec. 31 will be matched 1:1. Thanks for investing in our work!