Global media war for airwaves

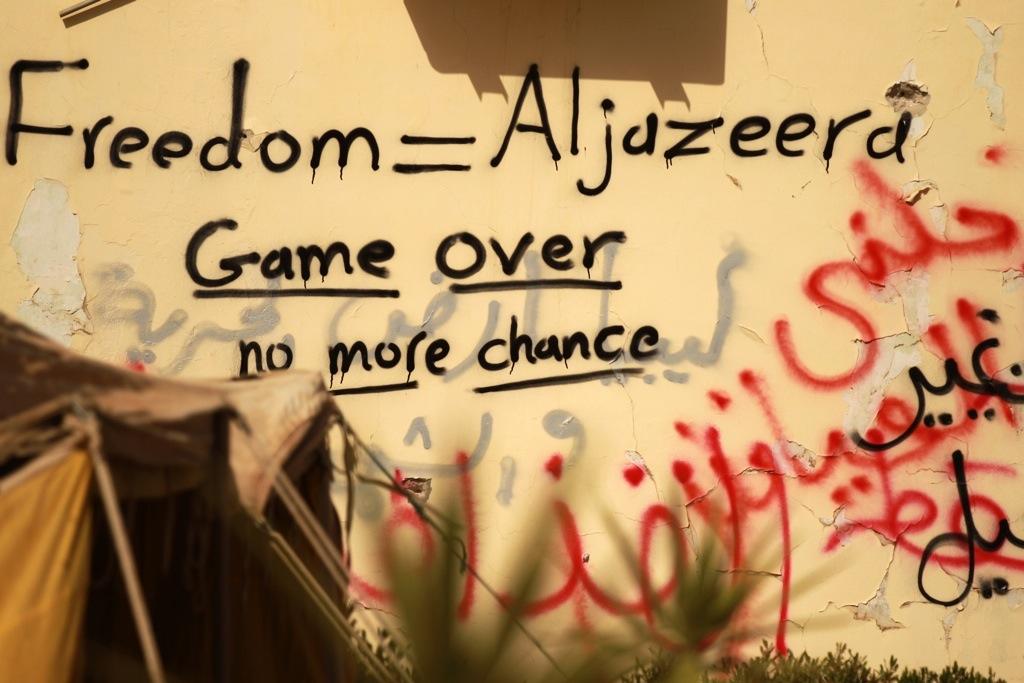

Graffiti praising Al-Jazeera on a wall in the eastern rebel-held Libyan city of Tobruk on February 24, 2011.

This report on Global Media Wars is a project by 15 reporters from the Columbia University Journalism School’s International Newsroom. The reporters monitored five state-funded English-language news channels whose programs are available via satellite, cable or internet livestream.

NEW YORK — The United States is at war. Again.

The new battlefront, according to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, is the increasingly crowded field of state-financed satellite television news.

The United States is “engaged in an information war,” Clinton told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in March, citing the emergence of international broadcasters Al Jazeera, Russia Today and China Central Television’s global English-language broadcast.

And, Clinton added with dramatic effect, “We are losing that war.”

Clinton was sounding the alarm about a fundamental change that is reshaping the global broadcast media arena. Where the BBC and CNN International once stood almost uncontested as the arbiters of global news, new 24-hour TV news channels have jostled their way into the market, shaking the longstanding primacy of Western media.

These new channels are aimed at viewers abroad and funded by various states. The governments paying their bills usually say they want to see their countries portrayed “fairly” to the world (as opposed to the way Western media may be portraying them). They also say their channels will show viewers the world as seen through their nation-centric lens. As they do so, they have begun to challenge some of the most basic tenets of American journalistic practice — among them, the concept of reporting objectivity.

“To be honest, I don’t know what objective journalism means,” Al Jazeera’s Washington Bureau Chief Abderrahim Foukara told TIME magazine in mid-February. “If you are an American network broadcasting from the U.S., you will be broadcasting with a sensibility that may not look necessarily objective to an audience in another part of the world. And the same is true if you’re a network like Al Jazeera Arabic, broadcasting out of the Middle East.”

Today, Al Jazeera’s English channel is the leading challenger to long-established global services like BBC and CNN International. But it is by no means alone in challenging the status quo. Since 2001, China’s Communist leadership has poured billions of dollars into the international broadcasting projects of its two state-funded media giants, Xinhua News and China Central Television.

The Kremlin’s Russia Today (now shortened to RT) has made impressive inroads using YouTube, as well as cable, to reach global audiences. Iran launched an international, English-language version of its own state-sponsored broadcasting station in 2007. From France, to Australia, to Venezuela, governments are funding media channels of various scales — all, it seems, intent on having their voices heard on the world stage.

Around the globe today, “everyone channel surfs,” said Enders Wimbush, a member of U.S. Broadcasting Board of Governors.

Wimbush was director of the U.S.-funded Radio Liberty in the closing years of the Cold War, when state-funded Western services like Radio Liberty and Voice of America provided vital shortwave radio broadcasts into the tightly controlled Soviet bloc.

Today, in his current role on the board of governors, he is tasked with overseeing the future of VOA and other American-financed broadcasters in a time of budget austerity. The competition from new global broadcasters is fierce, said Wimbush.

But, he adds, “My view is, let 100 flowers bloom.”

Secretary of State Clinton sounded less sanguine when she told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in March that America would have to step up its efforts if it wanted to maintain its position in the global media field.

“During the Cold War, we did a great job of getting America’s message out,” Clinton said, but after the fall of the Berlin Wall, programs like VOA were neglected, their mandates reduced. “Unfortunately, we are paying a big price for that,” said Clinton. “Our private media cannot fill that gap.”

“I think the United States is just not in the game,” agreed Columbia University President Lee Bollinger, who has called for consolidation of U.S. public broadcasting resources into a new, better-funded, globally-focused, American World Service, modeled on the BBC.

Bollinger argues that such a service would provide a vital, non-ideological counterweight to many of the newer global channels, though he acknowledges there is little likelihood of such an expansion right now. “It’s a pity for the world,” he said, “and a pity for the United States.”

If the U.S. is, in fact, losing the global information war, that is a dramatic turn from the past. Many of the emergent broadcasters say their mandate is to provide an alternate viewpoint in a conversation that has long been dominated by the voices of the United States, Britain and a handful of other Western countries with global media outlets. Today, CCTV-International seeks to be “China’s CNN.” Al Jazeera English purports to give voice to the voiceless — in other words, those regions and peoples neglected by the Western media.

In an increasingly interconnected world, a robust virtual presence becomes increasingly important. As Rome Hartman, executive producer of BBC World News America put it: “Every nation that is ambitious in terms of playing a global role … feels like they have to have a global voice.”

The proliferation of international state-sponsored broadcasters can also be understood as an attempt to extend power and promote policy. As it becomes harder for governments to suppress the flow of information, the role of soft power — of influencing opinions through information and argument, rather than by force — becomes increasingly important. The global media war is about shaping perceptions, rather than dominating them.

“Everyone’s going to advance their point of view,” said Kathleen Reen, a vice president at Internews, an international media development organization.

The question to ask now, says Reem, would be: “Who is actually taking in this information, and what are people doing with it?”

That’s a question without an easy answer. The Al Jazeera network now reaches 220 million households around the world, according to Tony Burman, chief strategic adviser for the Americas, and BBC officials describe the network’s English-language channel as the most serious of the new global competitors.

“We believe we are as global a news channel as exists,” Burman told a free press forum at Columbia University last November.

But international broadcasters seldom release concrete numbers on how many households are actually watching their programs, and their broad estimates are usually impossible to corroborate.

Many of the emergent state-sponsored broadcasters lack the funds or expertise to compete with longer-established and better-financed media corporations. Others target smaller, niche audiences. France 24, for example, operates channels in English, Arabic and French, and the French and Arabic services have built strong followings in its former African colonies and the Middle East.

But money isn’t everything when it comes to wooing a global audience. Despite a budget that is believed to be quite generous, China’s global English channel, CCTV-International, offers dull programming that reflects the heavy influence of the state that funds it. Few would regard it as much of a threat to other global broadcasters.

“You [the viewer] all are your own editors now,” said Simon Wilson, Washington bureau editor for the BBC.

As their access to information expands, he said, viewers “will pick on reputation and values. In this regard, I think the BBC has a great advantage.”

But the field of choices is increasingly crowded, and the BBC and other western media giants face increasingly sophisticated competition from all quarters. It will take more than reputation for any one voice to maintain its place in the conversation. As Internews’ Reen put it, we all have to “get more comfortable with a world that has a plurality of voices.”

Global Media Wars is a project of 15 reporters from the Columbia University Journalism School’s International Newsroom. The reporters monitored five state-funded English-language news channels whose programs are available via satellite, cable or Internet livestream.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!