The Great Bear Rainforest is a model for how to save trees

Grizzly bear cub in the Great Bear Rainforest.

In the summer of 1993, everyone I knew was chaining themselves to something. And where I grew up, on the west coast of Canada, the fight was over trees.

Environmentalists and aboriginal communities united to stop a company from logging in a remote place called Clayoquot Sound, on the far western edge of Canada.

More than 12,000 people blockaded a logging road into Clayoquot. Some chained themselves to bulldozers, others to trees.

Almost 1,000 people were arrested in the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history.

Related: The fight is on over grizzly hunting in the Great Bear Rainforest

Australian rock band Midnight Oil even played a concert in Clayoquot that summer to support the protesters.

It was the start of what became known as the "War in the Woods."

And if it was war, Valerie Langer was a general.

"Oh, I’ve been arrested several times," says Langer. Langer is a lifelong environmental campaigner. She currently works for STAND.

She helped organize the blockades back in 1993.

"I served time in jail for peaceful, non-violent civil disobedience,” says Langer.

Along with three months of daily roadblocks, Langer and her fellow activists launched a second attack — this one aimed at the wallet of forestry company MacMillan Bloedel.

“We were going around to their customers, getting contract cancellations so hundreds of millions of dollars of contracts were cancelled," says Langer. "So it was a very bitter conflict.”

The campaign discouraged international companies from buying timber from British Columbia.

For the logging industry, it was bad for business. For the government, it was a fiasco.

The BC government finally agreed to halt logging in Clayoquot. Seven years later, the area became a UN Biosphere Reserve.

But the logging war that began with that road blockade was hardly over.

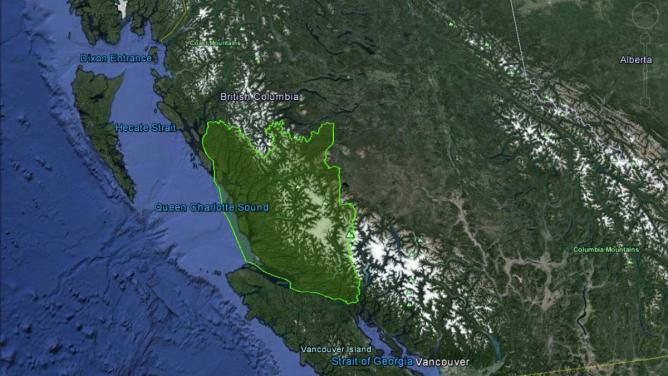

The next battlefield was an even more remote place called the Great Bear Rainforest, farther north on the BC coast.

The Great Bear is massive — almost 16 million acres.

It is part of the world's largest temperate coastal rainforest and it’s home to thousand-year-old cedar trees and some of the rarest animal species in the world — like the white Kermode bear that aboriginal people call the "spirit bear."

Twenty years ago, forestry companies held licences to log 95 percent of the old growth forest in the Great Bear.

But the BC government didn't want more blockades and boycotts — so it brought the environmentalists, aboriginal leaders and forestry companies to the bargaining table to try to figure out together how much of it would be logged and how much would be preserved.

It was an almost unprecedented approach. And almost no one involved thought it would work.

"I remember walking in and being faced by at least three or four really large middle aged men, usually with large bellies, who were just really imposing in a room,” says lead environmental negotiator Jody Holmes.

Holmes was one of the negotiators who worked on the Great Bear Forest deal from the beginning.

Forest industry negotiator Patrick Armstrong was there too. He says the animosity was thick.

Dallas Smith was also there at the start. Smith represented 15 Native American groups at the talks.

"I got there before the rest of my First Nations colleagues, so I grabbed a coffee and sat down at the table,” he says. “And one of the stakeholder reps sat down beside me and just as my chiefs walked in the room the stakeholder rep leans into me and says, I can't believe they let these goddamn Indians into this planning process.”

So that's how it started. Stereotypes and prejudices. Forestry guys are fat and greedy. Environmentalists are dangerous radicals. And then there are those goddamn Indians.

Holmes says the group worked with a mediator to try to steer away from the stereotypes.

The mediator had them eat meals together after meetings. He encouraged them to talk about their kids, their spouses, their lives beyond the negotiating table. To build relationships that might bridge their differences.

Smith says a major breakthrough came when the negotiators got fogged in and couldn't fly home after a meeting in a small, remote town.

“The local tavern had a $2 a drink night. Everybody, all the stakeholders, government, local government, we all just got shnuckered together. And the next day when we got back into the meeting room, everybody was so hung over but had fun the night before dancing and just having a good time that we're able to just sort of get past some of the crap that always started every meeting.”

The mediator encouraged them to leave their egos at the door, to see each other as human and respect each other's interests.

Forestry companies want to make money. Environmentalists want to save forests. First Nations groups want to have a say about the land where they live.

So they talked. And fought, and stormed out and came back. For thousands of hours and 20 years.

And then on Feb. 4 of this year, BC Premier Christy Clark formally announced the Great Bear Rainforest agreement.

“This decision protects 85 percent of the old growth and second forest growth. It preserves land in cultural and ecological and spiritual ties, which are vital to the people who have lived there for millennia and it includes more protected areas for freshwater eco-systems and species as diverse as the grizzly bear and the tailed frog.”

Going into the talks 20 years ago, 95 percent of the Great Bear was going to be logged. By the end, 85 percent was protected from logging. The deal is seen as a huge win for environmentalists.

But industry negotiator Patrick Armstrong says that it’s a recognition that times have changed.

“The outcome is actually a pretty good outcome for the industry. As important as having areas to log, is where those areas are, and what kind of forest are on those areas so I think it's a good deal for the industry but it is a major win for conservation.”

The War in the Woods that began in Clayoquot Sound, has ended — at least for now — in the Great Bear.

But the 20 years of negotiation produced more than a landmark deal for one place.

Campaigner Valerie Langer says it’s also a template for what could be done elsewhere.

“In the Amazon, the Boreal of Russia, in Indonesia, you have big companies, indigenous groups, environmentalists and government all in these same kinds of conflicts over the same kinds of issues — you are logging too much, you are mining too much, you are taking too much water out of that river, these are common problems," says Langer. "So the model of the solution is the biggest victory, I think, out of the Great Bear.”

Smith says he's already been consulting with other aboriginal groups about the deal.

"We've been able to work with other indigenous groups in the South Pacific, the Boreal forest here in Canada, some of the work that's been done in the Himalayas where we can talk about some of these things. And hopefully the time can be a little shorter now that somebody's actually broken the ice."

For Langer, it's been a long road since those days on the Clayoquot blockade in 1993.

She's still a big believer in civil disobedience. Just recently she was arrested for protesting a pipeline expansion in BC.

And she says all the effort is worth it when you get to save a place like the Great Bear Rainforest.

“It just goes on and on and on," Langer says. "And you fly over one fiord and over the valley and into the next valley, the archipelago of islands is sparkling off in the western sunlight. Everywhere you look, you're just looking at beauty.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!