El Narco: Meet DEA Agent Daniel

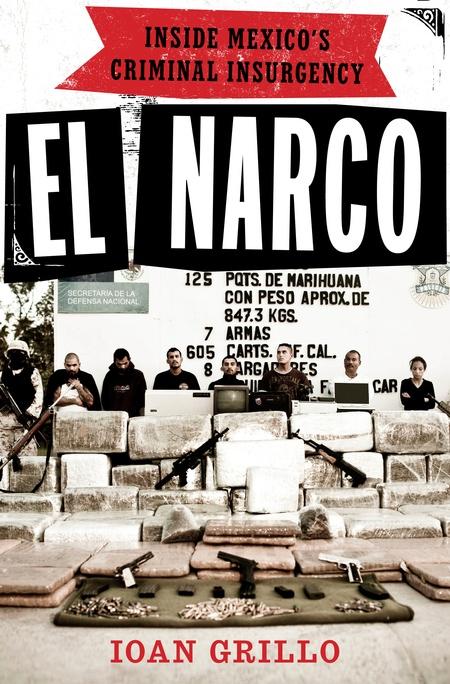

This is the first of three excerpts from Ioan Grillo's new book, "El Narco: Inside Mexico’s Criminal Insurgency," released by Bloomsbury Press on Oct. 25. In the book, Grillo interviews an American agent who infiltrates a drug cartel. Turns out, life inside is sometimes just like the movies. Editor's note: Strong language used throughout the excerpt may not be suitable for all readers.

“All my life I’ve tried to be the good guy, the guy in the white fucking hat. And for what? For nothing. I'm not becoming like them; I am them.” — Johnny Depp in Donnie Brasco, 1997

When DEA agent Daniel saw the movie “Miami Vice” at a cinema in Panama City, Panama, his heart jumped through his mouth. In the film — a remake of the iconic 1980s cop series — detectives Crockett and Tubbs run an elaborate sting operation on Colombian cocaine traffickers. Wearing their trademark white suits and t-shirts, they pose as freelance drug transporters so they can arrange to move a cargo of the White Lady, and then seize it. It sounds like a funny contradiction: cops transporting drugs so they can bust them.

But that is exactly the same sting Daniel was trying to set up in Panama in real life.

Daniel was also meeting Colombian cocaine barons, and he was also posing as a freelance drug transporter. After months of careful infiltration he was close to convincing the gangsters to put three tons of cocaine on a DEA-controlled ship sailing out of Panama City. It was the bust of a lifetime. And then Miami Vice hit the theaters.

If these gangsters see it, Daniel thought, he was dead.

“That was bad. I saw it and I was like ‘Ain’t that a motherfucker.’ We were completely compromised. This is bullshit. This is the same fucking thing we are selling. Because agents made that movie. That it is why it is so fucking solid. It is very, very close.

“Then you have to grow some balls. Fuck the movie. This is me. I don’t fucking care. That is the way I saw it at that time: make or break.”

Such a sting may sound like rather sordid business. It is. Drug busting is a grimy game. And in the modern drug war, it has become downright filthy. Agents have to get down in the trenches with psychotic criminals to get ahead of them. They have to recruit informants close to these villains. And they have to know how to use them to stick the knife in.

The huge drug busts aren’t made by luck and brute force. They are about intelligence, about knowing where the shipment is going to be or which safe house the capo will be hiding in next Tuesday. Only then you can send in the marines to start blasting. And this intelligence, as drug agents have found after four decades in the war, usually comes from infiltrators or informants.

Many narco kingpins are behind bars or on the concrete full of bullets because of treachery. And this makes gangsters so extremely violent toward suspected turncoats. In Mexico, they call informants soplones or “blabbermouths” and like to slice their fingers off and stick them in their mouths, in Colombia, they call them “toads.”

Related: Mexico's latest killers, the Mata Zetas

But once kingpins are extradited to the United States, many become toads themselves, super toads. They broker deals to give up other kingpins and tens of millions of dollars in assets. And then drug agents can make more busts and bring in more villains; and the jailed capos can write their memoirs and become movie stars.

This prickly prosecution process has been developed over four decades of the war on drugs, and it is crucial to understanding the future of El Narco in Mexico. Because a key question is whether Mexican and American agents can beat the beast of drug trafficking down by arrests and busts. DEA chiefs and the Calderon government keep pursuing this tactic. It has been hard and there have been a lot of casualties, they argue, but if they keep at it, then justice will prevail.

With their reign of terror, cartels often appear like invincible organizations, impervious to attacks from anything that police or soldiers throw at them. But if agents really got their act together would cartels collapse like paper tigers? Can the good guys actually win the Mexican Drug War and lock El Narco safely behind bars? Or at least if the police arrest enough kingpins, will drug smugglers stop being a criminal insurgency threatening national security and go back to being a regular crime problem?

More from Mexico: Murder-city opera

DEA agent Daniel’s own career offers startling insights into the attempt to put El Narco in jail. He has personally infiltrated a major Mexican drug cartel and a Colombian cartel. And he has lived to tell the tale. His story shows what the drug war strategy formed in Washington means on the streets of Mexican border cities.

Like many soldiers, Daniel comes from the rough end of town. DEA undercover agents are the coarse cousins of well-heeled CIA spooks. A Harvard-educated Anglo Saxon is unlikely to be any good setting up cocaine deals with the Medellin cartel. So the DEA needs people like Daniel, who was born in Tijuana, hung round with a California street gang affiliated with the Crips, and spent his teenage years beating the hell out of anyone who got too close. He was saved from a life of crime himself, he says, by joining the U.S. Marines. He went to Kuwait and fired a machine gun in the First Gulf War before going to the trenches in the drug war.

I meet Daniel in an apartment and he tells me his story over Tecate beer and pizza. He is powerfully built, wears a suit and tie and uses precise militaristic terms, common of veterans and cops. But his wayward youth also shines through and I catch him reciting old Hip Hop and punk songs from the eighties, from Suicidal Tendencies to Niggaz With Attitude. He also loves the 1983 gangster movie "Scarface." It helps to have the same cinematic taste as the mobsters you are dealing with.

“'Scarface' was the best movie ever. It was the American dream, especially to an immigrant; the dream of coming to America and being successful.”

Daniel already knew something of the world of drug trafficking when he watched "Scarface" as a kid in Imperial Beach, San Diego. He had spent his infancy over the line in Tijuana when the marijuana trade boomed in the seventies. One of his first memories was seeing his father invite strange men to their family home and pull stashes of money out of a secret compartment in a mahogany center table. Looking back, he believes his father was himself running weed. Then at age ten, his mother passed away and Daniel went to live with his grandparents in the United States.

“My mother was very hard with me and then she died five days before my birthday and I harbored a lot of resentment. That was one of the demons that haunted me throughout my life. I did a lot of things and I didn’t fucking care.”

Moving home and country was a tough challenge for a preadolescent. Daniel couldn’t speak fluent English until he was fourteen, and by that time he was a troublesome kid and got thrown out of three high schools because of fighting and other misbehavior. Some of his friends were stealing cars or motorcycles and bringing drugs over the border, and Daniel was smoking weed and getting drunk a lot, especially on peppermint and schnapps.

“I was one of those bad drunks who ruined the party. Every time I was about to get in a fight, I stripped off my shirt. I was very into lifting weights and I did wrestling in high school. I wanted to show off and say ‘Are you sure you want to fuck with me?’ It was a ritual.”

Daniel finally got his high school diploma at a last-chance school in San Diego. Then it was straight into the Marine Corps. He enjoyed the physical training and left behind the weed-smoking wastoid. Talented at a number of sports, he was selected for an elite unit within the marines and the military seemed to be a lot of fun. And then Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait and it wasn’t such fun anymore. After training in Oman, Daniel went into a hole in the desert and fired a SAW at Iraqi troops as they poured out of Kuwait City, probably killing many.

“It was sad because people surrendered. But some of them fought, especially the Republican Guard, so they got what they got.

“I froze my ass off. They said it was going to be hot so they threw all our cold weather gear away, Then it was fucking freezing. It poured and rained the whole time, and the holes would fill up with water. It was miserable.”

After four years in the Marines, Daniel went back to civvy street carrying some of his misery home in the form of Gulf War Syndrome, a condition believed to be caused by exposure to toxic chemicals, whose symptoms range from headaches to birth defects in the children of veterans. His military experience got him his first job busting traffickers, in California’s antidrug taskforce.

In the next excerpt, Daniel starts to learn the tricks of the trade.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!