US lawmakers: Colombia trade agreement sacrifices labor rights

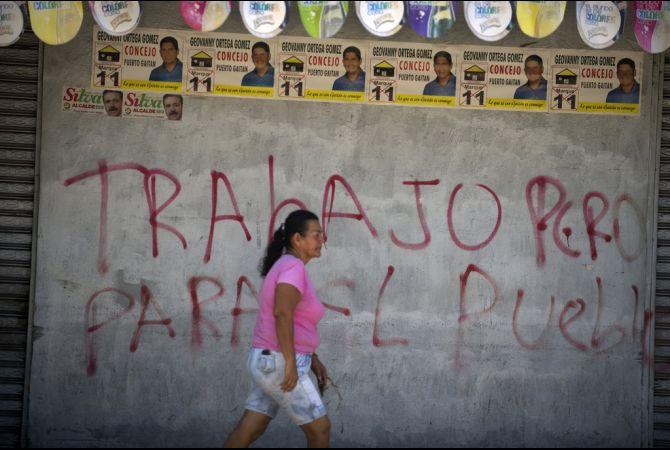

A woman passes by a wall with a graffiti that reads 'Work (yes), but for the people' in Puerto Gaitan, Meta department, eastern Colombia, on October 8, 2011.

BOGOTA, Colombia – When a work stoppage shut down production at Colombia’s largest oil field last year, government forces raided the strikers’ encampment and blockaded roads. With the strike broken, about 1,000 unionized oil workers were fired but others were allowed to keep their jobs in exchange for joining a sham, pro-company union.

Such union-busting tactics are common in Colombia and help explain why labor rights activists and some US lawmakers are dismayed by the Obama administration’s announcement that the US-Colombia Free Trade Agreement will take effect May 15.

“The president’s decision was premature,” Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Mass.) told GlobalPost. “This takes the pressure off the powers that be in Colombia from dealing with continued human rights violations against unionists.”

At the Summit of the Americas in the Caribbean port city of Cartagena on Sunday, the trade pact was hailed by both President Obama and his host, Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos, as the beginning of a new era of economic cooperation.

“We have gone from being good friends to being true partners,” Santos told a news conference.

But critics point out that a key side agreement – the so-called Labor Action Plan which sets benchmarks for improving labor conditions in Colombia – has yet to be fully implemented by the Colombian government.

In a joint statement, the leaders of Colombia’s two main labor confederations said declaring the Labor Action Plan a success would halt progress on labor rights, lead to backtracking, and remove a key incentive that had been motivating reform.

Colombia remains the most dangerous nation on earth for labor activists with nearly 3,000 murdered since 1986, according to Human Rights Watch. Only a tiny handful of the killers have been convicted. In addition, illegal firings and death threats often stop unions from forming in the first place.

More from GlobalPost: Targeting Teachers: The 'dirty war' against Colombia's unions

The ongoing repression had convinced many Democrats in the US Congress to oppose the trade pact. It was signed by the two countries in 2006 but languished as American lawmakers refused to vote on ratification. Signed last year by both governments, the Labor Action Plan side agreement was crucial for convincing several congressional Democrats to switch sides. The trade pact was ratified in October.

The Labor Action Plan contains 37 points and, by most accounts, has helped pave the way for improvements.

In February, for example, Colombian Labor Minister Rafael Pardo announced a broad crackdown against worker cooperatives. The co-ops are a major point of contention because they often serve as glorified temp agencies providing cheap labor to farms and businesses. Yet their members are considered small-business owners and are therefore banned from joining unions.

Union activists acknowledge that President Santos is a huge improvement over past government leaders, some of whom viewed unionists as communist guerrillas in disguise and looked the other way as they were gunned down by death squads. The Santos administration has even sponsored radio spots urging workers to join unions.

“It’s been a huge surprise for Colombians because now the government is saying that unions are good,” said Luciano Sanin, director of the National Labor School, a Medellin-based research center.

More from GlobalPost: Meet the New Boss: The rise of Colombia's labor co-ops

But now, Santos is taking heat from both sides — with union activists accusing him of not doing enough and some business leaders blaming him for backing down to Washington by signing off on the Labor Action Plan.

Either way, compliance with the plan remains a sticking point. Though the Labor Ministry is now hiring more inspectors, it has only about 1,200 officials to monitor abuses nationwide.

“We are making the system stronger,” Labor Minister Pardo said in a recent interview. “But we need more inspectors with more capacity. We have relatively few inspectors to cover the whole country. The laws are changing and we need them to be up to date on these changes.”

According to the National Labor School, lack of oversight is one of the main reasons why nine of the 37 points of the Labor Action Plan have been ignored while the remaining 27 have been only partially implemented.

In an April 10 letter to the Colombian Labor Ministry, McGovern and four other US lawmakers who are monitoring compliance with the Labor Action Plan laid out several specific problems.

In order to keep their jobs, the letter said, Colombian banana workers are often forced to prove to their employers that they are not affiliated with any unions. It said worker co-ops are being replaced by similar agencies under different names that continue to provide cheap, non-union labor.

The lawmakers also wrote that despite Colombia’s promises to increase the number of investigators and prosecutors, there has been almost no progress in legal cases involving trade unionists who have been threatened or murdered.

But the Obama administration apparently decided to overlook these problems and focus on the trade pact’s possible benefits. According to US government estimates, the agreement could help create half a million jobs in five years in Colombia, increase the country's output by one percent and lift 1.2 million Colombians out of poverty.

McGovern contends that Obama rushed his decision but said he probably wanted to come away from an otherwise lackluster Summit of the Americas with something concrete.

“I understand the desire to make a big announcement while the president was in Colombia,” McGovern said. “But a better announcement would have been: ‘You have made some progress, but there is still a ways to go.’”

John Otis is GlobalPost's correspondent in Colombia.

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.