Theologian Hans Küng condemns pope’s modern ‘Inquisition’

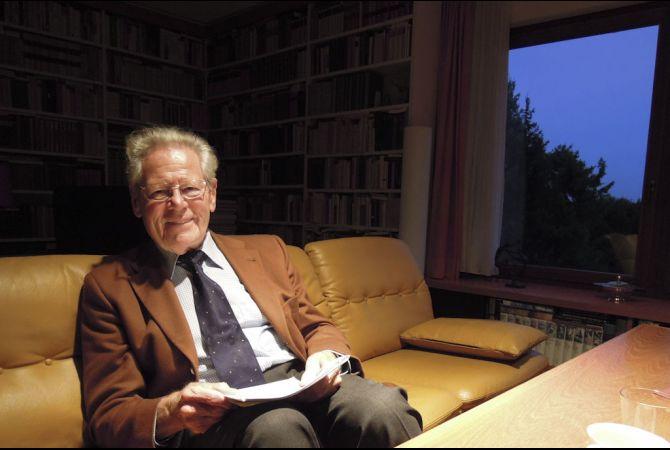

Hans Küng in his office in Tübingen, Germany.

TÜBINGEN, Germany — Fifty years ago in this medieval city with its steep hills and the sprawling campus of one of Germany’s great universities, Hans Küng and Joseph Ratzinger were priests and theology department colleagues.

Emerging out of the University of Tübingen, Küng and Ratzinger were the youngest and most influential progressives to advise bishops in Rome at The Second Ecumenical Council, or Vatican II, which began in the fall of 1962.

When Vatican II concluded in 1965 it unleashed an historic movement in the church toward greater engagement in the daily lives of People of God, as the council documents called rank and file believers. A new sensibility for justice and individual rights arose in the church that would grow to 1 billion Catholics worldwide, with missions of activism in many of the poorest countries on earth.

Back in Tübingen, Küng, a native of Switzerland, and Ratzinger, who had grown up in the Nazi darkness of his native Germany, soon found themselves at odds over the sweeping changes in the church, and a theological debate that would echo across Europe and the global church.

Now on the 50th anniversary of Vatican II, Küng, an internationally renowned scholar, and Ratzinger, known as Benedict XVI since his election as pope seven years ago, are even more at odds. Of the many issues that divide them, Küng sees the attempt to rein in the Leadership Conference of Women Religious as a sign of myopia, a failure of vision.

“You cannot deny that Joseph Ratzinger has faith,” says Küng, in a coat and tie, seated in his office, speaking in calm tones in the blue twilight. “But he is absolutely against freedom. He wants obedience.”

“He is against the paradigm of Vatican II.” Küng pauses. “He has a medieval idea of the papacy.”

“Many sisters are better educated and more courageous than a lot of the male clergy,” he says matter-of-factly. The Roman Curia “will try to condemn them.”

The legendary intellectual battle between Küng and Ratzinger holds a mirror to divisions in the larger church. Their split began shortly after Vatican II. During student revolts of 1968, Ratzinger was appalled when protesters disrupted his classroom. That same year, Pope Paul VI’s encyclical, Humanae Vitae, which condemned the use of artificial contraception, met with enormous protest from lay people, theologians like Küng, even scattered bishops.

Ratzinger shifted to the right, embracing institutional continuity. Küng attacked papal infallibility as an accident of history, devoid of genuine theological meaning.

Küng sees the clergy abuse crisis and the crackdown on the leadership council of American nuns as symptoms of a pathological power structure. By his lights, the impact on church moral authority, and finances, is a crisis rivaling the Protestant Reformation.

In his years at the university here, Ratzinger, polite and bookish, was a familiar sight on his bicycle. “He did not have a driver’s license,” recalls Hermann Häring, a retired faculty theologian who knew both men.

Ratzinger saw the church’s future in rebuilding its orthodox roots.

Polls since 1968 have shown that some 85 percent of Catholics do not follow the birth control teaching.

From academia Ratzinger rose to archbishop of Munich, then a cardinal appointed by Pope John Paul II as the prefect of the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, the old office of the Roman Inquisition. As he prosecuted theologians for straying from official teaching, he became known as an enforcer of truth.

Küng became a highly influential popular theologian with a stream of writings, including a book critical of papal infallibility. Ratzinger reacted with a CDF investigation and suspension of his license to teach theology. But at University of Tübingen, a public facility that dates to 1477, Küng had job safety. Still a priest, he became a pariah to orthodox Catholics and an intellectual hero to mainstream believers as he kept publishing and speaking.

As CDF proceedings targeted more church scholars, notably Charles Curran of America and Leonardo Boff, the Brazilian scholar of Liberation Theology, Küng likened Ratzinger to the Grand Inquisitor, in Dostoyevski’s “The Brothers Karamazov” — the sinister monk who tells Jesus the masses must be subdued by superstition for religion to maintain its power.

“You cannot be for human rights in society and not be for it in the church,” he continues. ”In Ireland, the prime minister is more outspoken than anyone” — referring to Enda Kenny’s blistering 2010 speech in the parliament attacking the Vatican for the rooted concealment of pedophiles. Ireland closed its embassy to the Holy See.

In the French edition of his new book (forthcoming in English as “Can the Catholic Church Be Saved?”), Küng expands on the analogy between a church that once put heretics on trial and injustice at the CDF under Ratzinger, as cardinal and now as pope.

“The Roman Inquisition continues to exist,” he writes, “with methods of psychological torture and the use in our day of many enforcement manuals.”

Küng, 84, expanded on the Inquisition theme in a Nov. 15 interview at his split-level residence, which also has offices for Global Ethic Foundation, which he founded.

“The [Roman] Curia realized that the practical life of nuns was different,” he says, “and that was enough to persecute them. You go to Rome for a hearing and it’s a dictate — take it or leave it.”

Küng and Pope Benedict personify the polarized camps as the church has evolved since Vatican II church. One side sees a church of rising aspirations in lay people, particularly women; the papal side seeks a return to deeper piety, a rules-based tradition that honors the hierarchy.

The monarchical notion of papal absolutism has Benedict XVI and John Paul II standing out in high relief from the clamor of Vatican II-inspired theologians and activists. Küng sees the CDF investigation of the nuns’ leadership group as symptomatic of papal retrenchment from Vatican II.

“Dissent is important in the history of the United States,” he explains. “The Catholic Church is different. They are persecuting people who are dissenting. … Is the church one boss who has the truth, and not much justice?”

Küng is not surprised that the climate of fear generated by the CDF has been met with silence by American priests.

“I have already written,” he says, as if the lesson should be memorized, “that one priest, acting alone, is nobody. Ten priests are a threat taken seriously. Fifty priests acting together are invincible.”

Küng has announced his retirement next year on turning 85. The handsome, book-lined home here in Tübingen will continue housing the foundation he launched. For a man of such fierce idealism, he seems a portrait in serenity.

“Most people do not remain in the church because they identify with the local bishop — or the church,” he says, as the lights of the town twinkle across the hills of Tübingen. “They are loyal to their community and not the Roman Curia.”

Research for this series has been funded by a Knight Grant for Reporting on Religion and American Public Life, sponsored by the Knight Program at the USC Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism; the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting; and the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.