In Tanzania, HIV at a crossroads

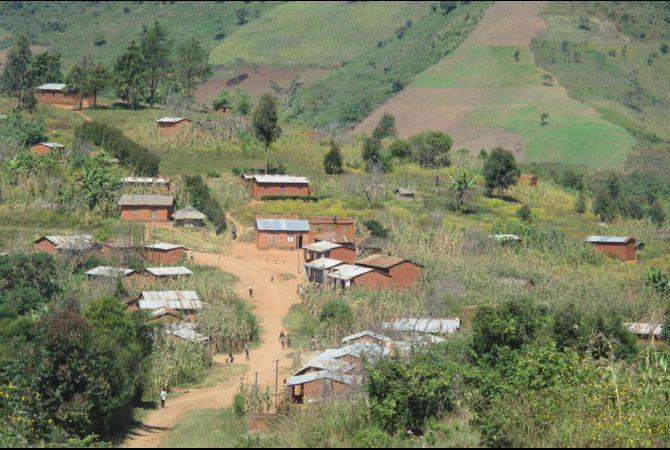

The village of Masita, Tanzania.

IRINGA, Tanzania – This ridge town is a stopping point for truckers headed to Malawi, Zambia and the Congo, and for migrant farmers on their way to harvest potatoes and tender tea leaves. Here at this crossroads lies the epicenter of AIDS in Tanzania, an intersection where scientists hope to unlock the secrets of stopping AIDS.

In Iringa and in three other sites in Africa, the United States and its African partners will be launching a combination of coordinated HIV prevention tools and strategies in the coming months that will test what President Obama and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton have been telling the world: An AIDS-free generation is now possible because the tools to prevent HIV infection are at hand.

No one yet knows whether they are soothsayers or false prophets. The trials may reveal the way ahead, or they may fall flat and leave the AIDS fight in a state of dangerous limbo.

The window of opportunity is small. Donors have started to cut back on AIDS funding. Most developing countries are still contributing relatively tiny sums of money. Success could mean more funding; failure could mean less. Life for millions hangs in the balance.

Off the traffic byways of Iringa, HIV flourishes in the murky and risky world of men looking for sex far from home and women looking to make a living in an economy that offers few options.

Still, there is guarded optimism that the scientists will find some success in their prevention trials. Smaller trials have shown the immense promise of various tactics when tried alone, notably the vaccine-like preventative effect on transmission when someone starts taking AIDS drugs, as well as the life-long protection afforded to many due to male circumcision. The trial designers believe if they can effectively stitch these programs together, the multiple approaches put them on the road to a Holy Grail: the numbers of HIV infections tumbling down.

For so long, the brains behind the fight against AIDS have sought a route to reverse a disease that flourishes for so many reasons, ranging from taboos of talking about sex to behaviors that have created high-risk populations whose Russian Roulette-like acts get them infected and then they infect others. Now many hope that this time by using several tools are once, they can change behavior and other some layers of protection, putting the worst of AIDS behind them.

Just one decade ago, experts from the CIA to the World Health Organization feared that AIDS would infect more than 100 million people, becoming a runaway epidemic and crippling countries. But the world, led by the United States, responded in a massive way and expanded treatment from tens of thousands to millions of people, leading to slight decreases in the past five years in the numbers of people living with HIV in countries from West to Southern Africa, where the epidemic has hit the hardest.

Is the world now at the next turning point in the history of AIDS? Is this a moment when AIDS, not countries, becomes crippled? Doubters are many. But many also believe new prevention tools and ramped up campaigns to protect newborns and women will help them finally outmaneuver a virus that has killed millions for decades.

“We need to put together all these things more than we have in the past,” said Brian Rettmann, the Tanzanian country coordinator for the US global AIDS program known as PEPFAR, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. “We’ve seen the global epidemic rate come down, but we don’t know what is figuring into that.”

‘The big bang’

Said one of the principal investigators of the Iringa combination prevention trial, Jessie Mbwambo, a researcher at Muhimbili University in Dar es Salaam: “The time for small steps is now over. This will be the big bang.”

In sub-Saharan Africa, where more than 23 million people — or two-thirds the global total — are HIV positive, the strategies to prevent HIV transmission have gone through major changes in the last five years, dating to clinical trials in 2007 that showed male circumcision reduced chances of infection by at least 60 percent.

In remote areas of south-central Tanzania, near the Malawi border, large-scale male circumcision campaigns were under way last month, with some of the demand sparked by women forcing men and boys to go. In the town of Makambako, USAID-funded workers were teaching sex workers about “kitchen gardens” and how to take care of livestock, two alternative — and safer — employments. Others in town visited trucker hangouts to encourage safe sex and HIV tests.

These efforts, now done separately by various contractors, will be forged together for the pool of trial participants so that anyone receiving any HIV prevention tactic can be offered all of the tactics. It will be kind of like entering a supermarket of HIV prevention, with checkout clerks not giving away just one free handout, but multiple gifts at a time.

“To combat HIV/AIDS you need to combine strategies,” said Robert Mahimbo Salim, the Tanzania government’s regional medical officer in Iringa, after visiting a male circumcision campaign near Tanzania’s border with Malawi. “We need to do more counseling and testing for HIV, put more people on treatment, and now get more men to be circumcised. Iringa has three times the national prevalence of HIV. It’s a very big problem.”

Fervent supporters of male circumcision

Sitting across from him, Hally Mahler, the director of a USAID-funded male circumcision program in Tanzania run by Jhpiego, an affiliate of Johns Hopkins University, said that those who work on male circumcision campaigns almost always become fervent supporters of the procedure because of its impact. Jhpiego has helped circumcise roughly 100,000 men in Tanzania in the last 30 months. In a six-week campaign ending in June, the group oversaw the circumcisions of 25,840 adolescents and men.

“You drink the Kool-Aid,” she said, explaining that clinical trial results have made believers even out of the most hardened cynics. AIDS modeling, she said, has made their work tangible: “You have 100 people in the waiting room (to be circumcised) and you count every six of them and that’s how many HIV infections are averted because of circumcisions.”

For Mahler, a high-energy mother of two who has been working in Tanzania for six years, the expansion of male circumcision in Tanzania amounts to “creating a whole new social movement.” Driving the demand, she said, are women encouraging their male partners to be circumcised for both hygiene and HIV prevention reasons.

Withholding sex

In some villages, women are telling men if they aren’t circumcised, they will withhold sex.

In the village of Masita, Maria Komba, 32, said that’s what she and her girlfriends did. It worked, she said.

“We women have talked,” she said smiling in her shop at the center of the southern Tanzania village of 1500 people, one truck, 20 motorcycles, 200 cows, 5000 goats, and corn stalks 10 feet tall. “We have taken a stand that men should go and have it done and if they don’t, that’s it. We’re going back to our mothers and leaving them.”

Standing next to her was her husband, Yohanna Mwinuka, 31, who followed his wife’s suggestion and was circumcised, along with their 10-year-old son Alpha, a week before. He grinned, shyly, and pulled his baseball cap down over his face.

When he looked up, he acknowledged she was truthful. “We had discussed it,” he said. “And my wife told me, ‘I will escort you there to be circumcised.’ It was showing that this is all about doing it together. It was a show of love.”

Sex workers become farmers

In other communities, other prevention tactics were in motion. A three-hour drive north, in the crossroads town of Makambako, Penina Mnyili, 36, a mother of five, said a series of lessons supported by the PEPFAR-funded The ROADS project helped her make the transition from a local brew seller and sometimes sex worker to a small-scale farmer growing vegetables and raising a pig. One of the key lessons from the FHI 360-run program, she said, was how to save money.

“Before, I didn’t know how to save money,” she said in her small backyard with several plots full of spinach, beans, potatoes and a natural herb that kept pests away. One large plastic sack, full of soil and manure, sprouted lettuce and spinach on top and all around the sides, from holes cut out of the fabric.

Mnyili stood beaming next to her crops. “It’s been such a big change for me. For one thing, I’m no longer dependent on my husband to buy our food,” she said. “Now I am growing our greens, or I can sell them and buy meat. I am earning enough money to pay the school fees for all my children. This has given me confidence and much more independence.”

At a nearby truck stop, where workers for The ROADS stop by daily to spread HIV prevention messages and to make sure a condoms dispenser is full, Mohamad Ameeri, 57, nursed a Castle beer and said it’s hard for truckers to avoid HIV messages now.

HIV tests at Congo’s mines

“If you go in and out of the mines in Congo” – where he was headed – “they always ask you if you have taken an HIV test,” he said. “They also will give you a pack of condoms when you go through the gates.”

The way to fight AIDS, he said, is “education, education, education. Condoms are helpful, but you need to be educated about the dangers. You could be drinking like me and then you need to be constantly reminded with cautionary messages.”

Behind him at Mama Kaduma Restaurant, a woman served beer to another man. “She’s a sex worker,” Zayane Ng’umbi, who works on The ROADS project, said softly, nodding in the direction of the woman. “Her mother is the coordinator of all the sex workers here. There are about 30 sex workers, and they are very cooperative with us. We hold what we call Moonlight Tests during the night, and all of them agree to be tested for HIV. Always.”

This effort with truck drivers and sex workers is one piece to the future of fighting AIDS, say experts. But these pieces of the fight have often operated in their own orbits, disconnected from any other prevention efforts. Groups working with truck drivers, for instance, may never have connected the men to circumcision services; or groups providing help to pregnant teens may have been powerless to try to keep those young women in school.

Trials: $60 million price tag

The three upcoming HIV combination prevention trials will start this fall and are expected to run a minimum of four years, at an initial cost of $60 million. They are designed to each have multiple approaches that will reach truck drivers, sex workers, migrant farmers, injectable drug users, and men and women who have multiple partners.

Each trial will have a similar base: A control group that will receive the current level of AIDS prevention, and a randomized group will receive a larger package of prevention services.

The ramped up package will start HIV-positive people on treatment earlier, expand male circumcision programs, and increase community education on risky behaviors.

Then each trial will add a wild-card element, designed to see which of these other efforts works most effectively.

In Iringa, a region with 1.6 million people, that means teen-aged girls and young women in their early 20s will be offered small cash payments to stay in school.

In Botswana, it means starting treatment much earlier than the other sites – at the level of a 500 CD4 count, instead of the 350 level now recommended by the World Health Organization. CD4 cells are a type of white blood cell that fights infections, and a CD4 count gives a good sense of the strength of a person’s immune system and its ability to fight diseases. The higher the count, the stronger the immune system.

In Zambia and South Africa, it means ramping up counseling and testing of people and linking more people into AIDS treatment.

Iringa was chosen as a trial site because of its relatively low level of services and its extremely high HIV prevalence, 15.6 percent of all adults aged 15 to 49, compared to the national rate of 5.6 percent.

HIV and the road

Here, HIV follows the road. Large numbers of truckers stop in Iringa, helping fuel a highly risky sex trade. Migrant workers harvesting tea leaves, coffee beans, cocoa, potatoes and bananas are away from home for months. Infections easily skip into the general population, as high-risk groups pass the virus on to their regular sex partners.

“It’s a recipe for HIV transmission,” said Daniel Moore, deputy country director for the US Agency for International Development.

The details around the trial in Iringa were still being finalized this month. But by all accounts, the scope of the work will be huge, involving 12,000 participants and adding “thousands” of health workers, Rettmann said. Still unknown is how the trial site will secure that many workers. Also not settled is the amount of cash payments to girls, or how the money will be transferred to potentially thousands of them.

“With this cash transfer, we want to see whether the behavior is different in young women,” said David Stanton, USAID’s division chief of Technical Leadership and Research in the Office of HIV/AIDS, and a chief architect of the trials. “We want to see if they reduce the number of sex partners.” Earlier studies done by the World Bank in Africa have shown some reductions in infections.

Questions about trials’ approach

Some HIV prevention experts have questioned parts of the approach, including the cash transfer as well as whether increasing treatment will significantly prevent infections. The doubts on treatment-as-prevention have come about because the clinical trial looked at HIV passed in a relationship in which one was infected and the other not; skeptics note that roughly one third of all infections happen in sex outside of those central relationships.

Mitchell Warren, executive director of AVAC, a global non-profit advocating for HIV prevention initiatives, said people shouldn’t have too high or too low expectations from the scientific trials.

“We have to be realistic that treatment in and of itself is not going to end the epidemic,” he said. “The best method is to provide the most options to the most people. Each of these methods has real-world challenges. The challenge is how do you put it all together? How do you recognize that each of these has deficiencies?”

Outside trials, what’s next?

The results from combination prevention trials may not be fully available for several years, which raises another pressing issue: What should be happening in the meantime? Can the United States, other donors, and developing countries afford to start scaling up prevention tactics in other high-risk populations?

Or, can they afford not to?

“In the fight against AIDS, we’ve always had turning points and critical moments,” Warren said. “This is a major turning point now. If we don’t do the right things now, doing them in five years time is going to be a lot harder, with many more people infected. The mountain becomes that much higher, and the cost that much greater.”

Video: John Donnelly in Tanzania

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.