Syria’s civil war emphasizes Middle East’s deep Sunni-Shia division

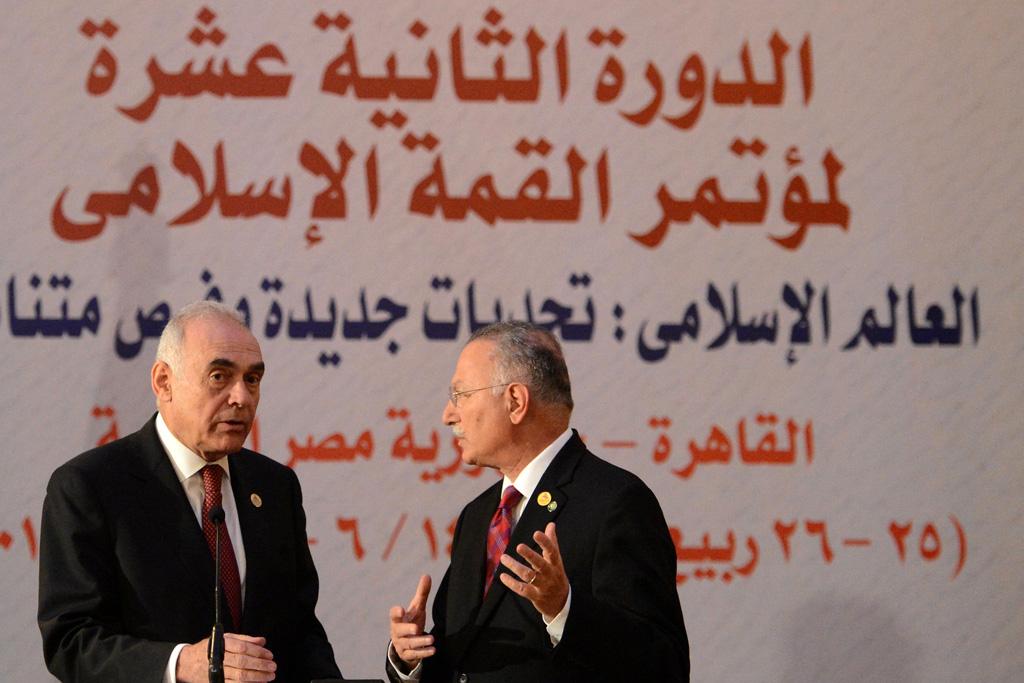

Secretary General of the Organization of Islamic cooperation (OIC) Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu (R) talks with Egyptian Foreign Affairs Minister Mohamed Kamel Amr as they give the final press conference at the end of the 12th summit of OIC. The summit was dominated by the Syrian conflict which has divided the Muslim world along sectarian lines.

CAIRO — The ominous backdrop of civil war in Syria has exposed a Sunni-Shia sectarian fault line that was trembling at the summit of Islamic nations, which came to a close Thursday.

The crisis in Syria, observers here said, has become a kind of proxy war in the Sunni-Shia divide.

It was clear at the two-day summit of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) that Iran’s Shiite theocracy is unwavering in its support of the regime of Syrian President Bashar al Assad. Led by an Alawite minority that is considered an offshoot of Shiite Islam, Assad’s regime stepped up its pounding of the opposition, even as the delegates of the 52-nation regional organization were convening.

Meanwhile, the predominantly Sunni nations of Turkey, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states that attended the summit made it clear they were putting their regional clout and their petro dollars behind the still ill-defined Syrian rebel forces, which are suffering enormous casualties in a war that has already claimed 60,000 lives.

In his remarks to heads of state at the OIC, Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi sharply criticized Assad’s regime. But Morsi stopped short of publicly calling for Assad to step down.

Seeking to restore Egypt’s traditional role as a diplomatic power broker in the region, Morsi, an Islamist leader whose political party grew out of the Muslim Brotherhood, was restrained in his remarks. Some political analysts observed that he seemed to be going out of his way not to alienate Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, whose visit to Cairo marked the first time an Iranian head of state had visited Egypt since Iran’s 1979 Islamic revolution.

With Cairo’s streets still simmering with protests against Morsi’s government and 26 heads of state in attendance for the OIC, the conference hall and hotel where the events was being held looked like an armed camp, ringed with razor wire and Egyptian army tanks.

The atmosphere in Cairo was tense throughout the summit. To many observers, the diplomatic maneuvering seemed to take shape along the lines of a Sunni-Shia divide, a perilous fault line that has torn the region apart for decades.

One of the more difficult diplomatic postures was held by Iraq. Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, whose Shiite-led government has been somewhat ambivalent about the Syrian conflict, took a cautious approach in his remarks. After all, Maliki’s regime would effectively be weakened if a Sunni majority came to power in neighboring Syria. Maliki has faced sharp criticism, and at times militant opposition, from Iraq’s Sunni provinces.

You could hear the hesitancy in Maliki’s voice as he said, “Syria suffers from violence, killings and sabotage.” He called upon the OIC to help Syria “find an exit and a peaceful solution for this conflict.”

Not exactly strong words against the regime of Assad, who was officially removed as a member of the OIC at its last gathering.

Another delicate dance of diplomacy on the sidelines of this gathering was among the so-called “quartet” of regional powers, which Morsi has openly been trying to assemble to address the Syrian crisis.

But it was unclear whether Morsi succeeded in convincing the Saudis to take part in a ‘working group,’ and several Egyptian political commentators inside the gathering said that the Saudi foreign minister had left the OIC early. The Saudi kingdom and other Gulf states have shown little patience for Morsi’s Islamist government, perhaps fearing that rising Islamist movements could wreak havoc elsewhere in the region.

Morsi, who has sought to thaw Egypt’s relations with Iran, has a difficult road ahead in pulling this working group together. Bitter historical divisions between the region’s Sunni and Shia still shape, and often rupture, the terrain.

It has been said that Egypt and Iran are the only two real countries in the Middle East, the rest are “tribes with flags.”

Karim Sadjadpour, a researcher for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said in an interview with the BBC,“It is very interesting that these two countries are developing a relationship.”

Egypt and Iran “don’t see eye to eye on many issues, and Syria is one of them,” said Sadjadpour, adding that Iran is drawn to Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood in large part because they challenge US policy on Israel.

“The way Iran sees it, what is bad for the US is good for Iran,” said Sadjadpour.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!