Silk Road: Can an eBay for meth, smack and pot prevail?

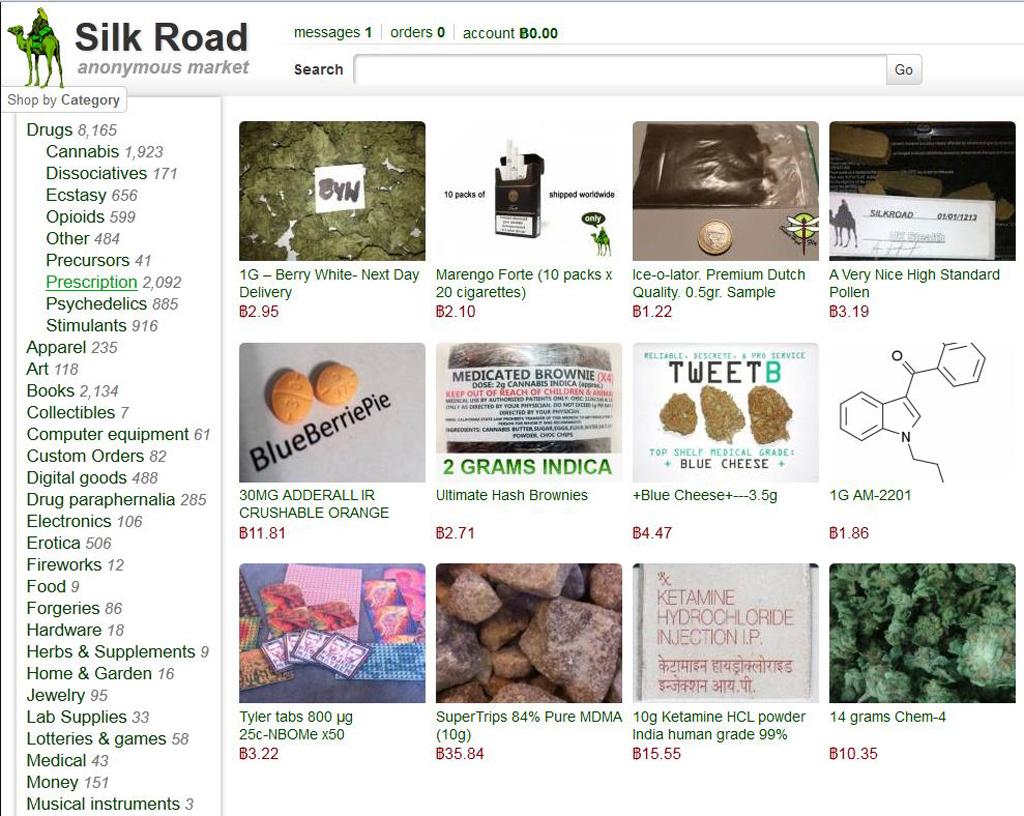

A screenshot of Silk Road’s website.

ATLANTA — Senator Chuck Schumer called it "a certifiable one-stop shop" for meth, heroin and cocaine, "the most brazen attempt to peddle drugs online that we have ever seen."

That was in June 2011, just days after Gawker writer Adrian Chen outed the site, known as Silk Road.

Schumer's outrage was palpable. He commanded Attorney General Eric Holder to shut down the clandestine marketplace.

But in the nearly two years that have passed, that apparently hasn't happened.

The site mysteriously disappeared for two weeks in November 2012, and its proprietor, alias Dread Pirate Roberts, went incommunicado from online forums. That led some to speculate that law enforcement had shut it down.

But the opposite now appears to be true.

Due to an explosion in popularity, Silk Road's infrastructure had to be rebuilt to accommodate new customers and security, Dread Pirate Roberts said in a post following his return. And performance measures were added to better protect users.

Rather than getting busted, Silk Road appears to be getting more robust.

In early 2012 the site was carrying out "slightly over $1.2 million per month" in transactions, according to a study by Carnegie Mellon professor Nicholas Christin, who conducted "daily crawls of the marketplace for nearly six months in 2012." And business was growing steadily, albeit not "exponentially, as reported in forums," Christin reports, resulting in commissions of $92,000 a month for the site itself.

That, of course, is pocket change in the world of transnational drug trafficking, where hundreds of billions of dollars change hands every year. But as Schumer's comment reveals, Silk Road's overt flouting of the law raises heckles.

Silk Road is by no means the first online marketplace for illicit drugs. Others have included Black Market, The Armory, Reloaded and General Store.

Law enforcement agencies around the world are fighting an arduous battle with these sites, albeit with some success.

Eight individuals were arrested in the US last year in connection with online drug trafficking, although none involved Silk Road. Australia nabbed the first Silk Road-related conviction in February 2013, when a Melbourne court found Paul Leslie Howard guilty of selling cocaine, MDMA, amphetamines, LSD and marijuana. He faces three to five years in prison.

While law enforcement authorities are eager to shutter Silk Road, knowledgeable sources say doing so will be challenging, thanks to the elaborate measures the site has taken to protect its clients.

"Silk Road is something we are aware of," said US Drug Enforcement Administration spokesperson Rusty Payne.

"Internet drug trafficking is really difficult to enforce. There are a lot of challenges, and a lot of technology that makes it difficult for law enforcement," Payne said. "Many times, it's easy to hide behind a server."

Hiding from authorities, while making itself available to those in the know, is precisely what Silk Road is all about.

For starters, you can't find it through Google, nor is a visit as simple as typing silkroad.com. To maintain customer anonymity, the site is only accessible through TOR, a decentralized server network that lets users mask their online identities and encrypt their internet connections. Once you get on TOR, Silk Road's web address is not very viral: ianxz6zefk72ulzz.onion.

While TOR's strength means there's little chance that authorities can identify dealers and customers on the site, another potential choke point involves the currency used to conduct the transactions.

To avoid the easily-tracked trail left by credit cards, customers must make purchases using bitcoin — a digital currency championed as a way of maintaining online privacy. Bitcoin is not completely anonymous on its own, but it can be customized to obscure a user's identity.

"I call it user defined anonymity because it's not anonymous out of the box. It's anonymous only for careful users," said Jon Matonis, an e-money researcher, former Hushmail CEO and member of the bitcoin foundation. "Just like you practice safe sex, you have to practice safe bitcoin."

Increasingly, law enforcement agencies are hostile to bitcoin, regarding it as a black market currency.

"Bitcoin will likely continue to attract cyber criminals who view it as a means to move or steal funds as well as a means of making donations to illicit groups," read a report released by the FBI last year. "If bitcoin stabilizes and grows in popularity, it will become an increasingly useful tool for various illegal activities beyond the cyber realm."

Still, law enforcement agencies are thought to be devising strategies to take down online offenders using vulnerabilities posed by bitcoin.

And banning the service would come with its own collateral impact. For example, bloggers in places like Saudi Arabia and Vietnam can use bitcoin to pay for hosting services on WordPress, reducing the likelihood that local authorities could discover their identities.

"In the long run [law enforcement] will be looking for some regulatory choke points and they're going to be disappointed," Matonis said. "Bitcoin is not illegal in any country but it's also not currency. You're trading a math puzzle."

For now, Bitcoin remains a relatively minor concern; its value in circulation amounts to "only about $130 million in total," added Matonis, and drug trafficking is thought to account for a small fraction.

"That's like money that falls into the drug dealer's sofa," Matonis said.

But in spite of law enforcement's struggles in policing the online drug trade, Silk Road user anonymity may not be as ironclad as customers believe.

While internet denizens widely trust that the TOR network will maintain anonymity, that confidence may be misplaced.

"It is not impossible to crack TOR network. It's notoriously bad from a security prospective," said Richard Stiennon, author of "Surviving Cyberwar" and chief research analyst at IT-Harvest, a digital security firm. Stiennon also noted that he had personally witnessed the TOR network being cracked and exploited.

Law enforcement has already shown itself able to breach online "anonymizers." In 2012, for instance, there were a number of arrests of hackers involved in online collectives like Anonymous.

"I've seen in the last two years a rapid learning curve [that law enforcement] has climbed. They're able to infiltrate networks, pose as members of the community, interact and get enough information to identify people," Stiennon said.

While there are a plethora of anonymizers available to users, the level of trust placed in organizations and developers behind the software is in many cases unjustified. Companies often claim that server logs and other user information are not kept on file but such claims are virtually impossible to confirm.

"A lot of anonymizers claim they don't keep logs but how do you know that's the truth?" Stiennon said.

To stem the flow of drugs into the online market, law enforcement may need to rely on the skills acquired in policing hacker collectives rather than regulating a burgeoning market for online currency. In spite of bitcoin's use for illegal online purchases, the transaction is not dissimilar from a typical cash purchase of drugs in the real world illicit marketplace.

"With paper cash, you have privacy. You can go out and buy whatever you want with cash anonymously and it's untraceable. If a woman wants to pay for an abortion anonymously but she doesn't want to have her credit card used in the transaction, she can still go and pay with cash," Matonis said. "We already use paper cash anonymously and untraceably in our lives today. The only thing bitcoin does is retain that same privacy in the digital environment."

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!