Over 150,000 people living in secret North Korean gulags

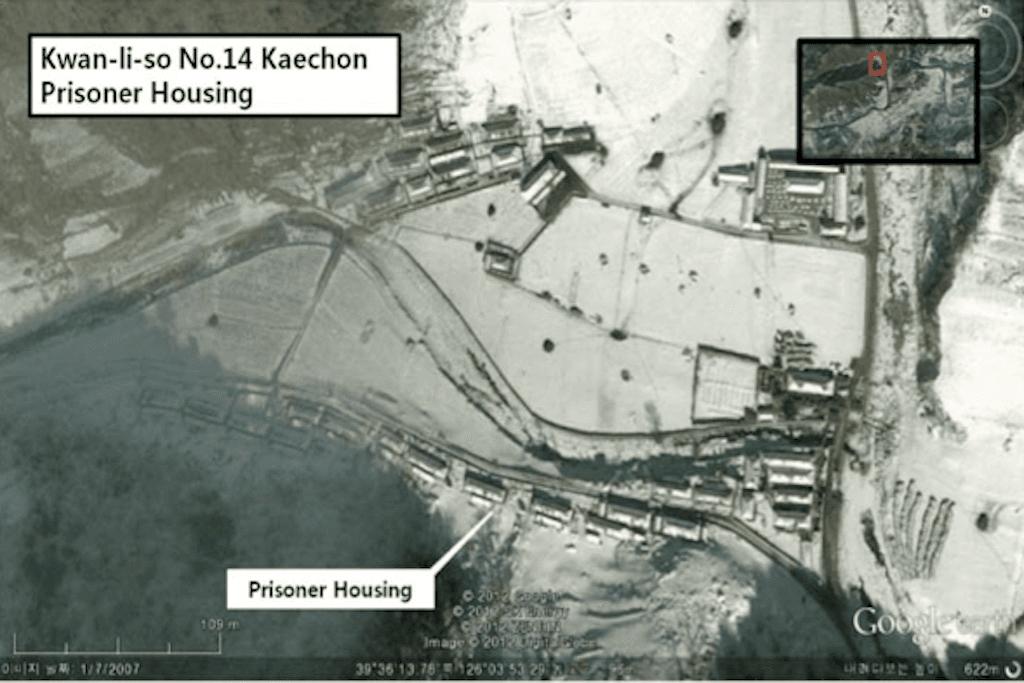

A satellite image of one of the secret North Korean gulags described in David Hawk’s report.

North Korea routinely denies their existence, but a report by professor and human rights advocate David Hawk and the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea uses extensive research, satellite photos, and interviews with former guards and inmates to prove that North Korea operates secret prisons and labor camps. The report, “The Hidden Gulag: Exposing North Korea’s Prison Camps,” [PDF] is an updated version of a 2009 original.

The camps are called kwan-li-so, which loosely translates to "political penal-labor colony," but in Korean, what they really mean is "management center" or "re-education center." The prisons are located in the central and northern mountains of North Korea.

Each houses between 5,000 and 50,000 people who are "real, suspected or imagined wrong-doers and wrong-thinkers, or persons with wrong-knowledge and/or wrong-associations who have been deemed to be irremediably counter-revolutionary and preemptively purged from North Korean society," according to the report. In total, there could be as many as 200,000 people who have been forcibly removed from society and imprisoned without charge or trial.

The practice of removing people — and sometimes up to three generations of entire families — has been going on since the 1970s, and the original model for the North Korean camps were Soviet gulags. But, according to Hawk, who is a noted professor and human rights advocate, the North Korean state has taken the Soviet idea and morphed it into "a truly totalitarian level of individual monitoring, reporting, and control without precedence in human history."

Once removed to a camp, prisoners generally receive a life sentence. They are effectively erased from their former lives and enter a world of absolute terror. "The prisoners live under brutal and severe conditions in permanent situations of intentional, deliberate semi-starvation. The kwan-li-so are usually surrounded at their outer perimeters by barbed-wire (often electrified) fences, punctuated with guard towers and patrolled by armed guards."

The United Nations' basic "Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners" is (not surprisingly) flouted in the most egregious ways in these North Korean camps, and inmates are "grossly ignored or abused." Former prisoners and escapees interviewed for Hawk's report recall witnessing or hearing about forced abortion, forced mating, beatings, sustained malnutrition, infrequent bathing privileges, and insufficient medical care that results in missing fingers and limbs, in addition to the labor they're forced into, usually logging or mining.

"Conditions drive people to violence and aberrant behavior. Former prisoners report that inmates beat each other in retaliation for the non-achievement of production quotas for which the entire work unit will be punished. Prisoners fight each other over scraps of food, or over the clothing of deceased inmates," according to the report, and "one interviewee said she was in such pain that she begged her jailers to kill her to end her suffering."

What can be done about this?

Not much, apparently.

But Hawk does include advice to groups of nations (such as Japan, South Korea and the US), as well as the UN member states, including pointing to the camps in any future negotiations with North Korea. The last section asks for North Korea to consider allowing the Red Cross access to the kwan-li-so, among other "reccomendations" — like ending the practice all together. Since the death of Kim Jong Il in 2011, the international community has hoped his son and successor, Kim Jong Un, would end some of the more barbaric aspects of the dynasty's regime and end the "dense fog" of secrecy of North Korea, but Kim Jong Un hasn't given an indication that this is a realistic dream.

"For too long, it has been considered too difficult, too controversial, and too confrontational to point to the camps in discussions with North Korean officials," said Roberta Cohen, chair of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea. "That is precisely why the report’s recommendations are so important in calling for access to the starving, abused and broken men, women and children held captive."

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?