New dangers threaten Kenya’s Kakuma refugee camp

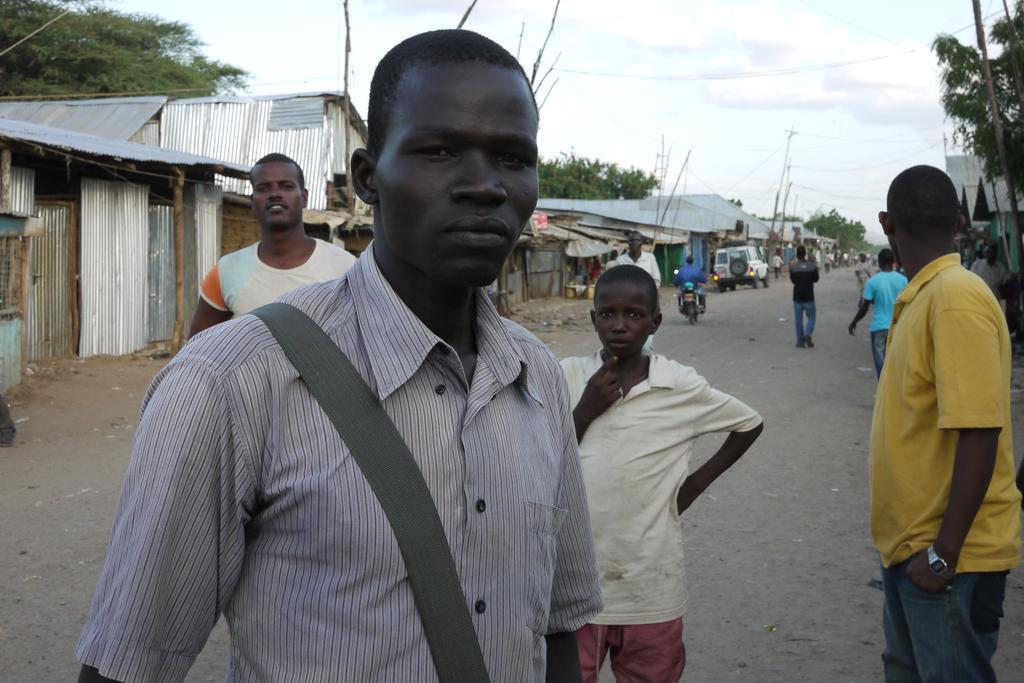

Reth Maker, who has lived in Kakuma for two decades, was one of Sudan’s “Lost Boys” when he arrived in 1992 at the age of 5. He is now a teacher in one the camp’s schools, and dreams of one day starting a family, but know he has few prospects.

KAKUMA, Kenya —The Kakuma refugee camp is 60 miles from Sudanese border, in the uppermost reaches of the arid Turkana region of Kenya. It was opened in 1992 to house the 16,000 “lost” girls and boys fleeing the war from Sudan. These days, the overcrowded facility is home to around 100,000 people, driven there by violence not only from Sudan but also Ethiopia, Congo, Somalia, Rwanda, Burundi and a handful of other nations.

Kakuma does not look like a refugee camp in the movies, with rows of canvas tents ringed by barbed wire. Or rather, structures like that do exist, but that is where the aid workers live. Most of the refugees live in handmade huts, built of sticks, mud, metal scrap, and materials salvaged from aid packaging.

At the camp’s entrance, myriad signs list Kakuma’s sponsors, which include the United Nations’ refugee agency (UNHCR), The Lutheran World Federation, The World Food Program and Handicap International. The latter advertises a “mine risk education program.” Poisonous spiders, snakes, and scorpions abound in the area.

Life in the camp is hard, and it is about to get harder. Poorly funded infrastructure means that disease is always a threat. The coming rains could overwhelm the already overstretched water and sanitation facilities, said aid officials on the ground, who worried about overflowing toilets and outbreaks of diarrhea, pneumonia, measles and cholera. One third of the camp’s population lacks adequate shelter, according to the UN. Even firewood is scarce; some people actually have sold their food rations to buy wood to cook with.

Why are things in such bad shape in the two-decade-old camp?

“Apparently it’s a question of budgets,” an aid worker said with resignation.

The second threat is terrorism. Now, with the success of the Kenyan army in pushing back al-Shabaab, there is concern that members of the militant Islamic militia may try to infiltrate the camp. This appears to have happened already in the Dadaab refugee camp, close to the Somali border, which is beset by improvised explosive devices and kidnappings. The concern is that Shabaab soldiers could simply shave off their beards and enter the camp with those fleeing Somalia and nobody would know, said an aid official on the ground speaking off the record.

More from GlobalPost: Foreign aid workers kidnapped from Kenya released in Somalia

Violence between refugees of different nationalities crammed together is a persistent problem. Sexual violence remains an issue, with hundreds of cases reported every year. There are also more than 57,000 children in the camp, about 5,000 of whom have no parents. A lack of funding means that services to them are limited.

An August statement from UNHCR described the situation in the overcrowded camp:

“The provision of life-saving assistance and important services is becoming increasingly difficult due to limited funding to cater for the growing population, particularly in the shelter, sanitation, education, and healthcare sectors. The sustained rate of new arrivals to the camp has already depleted all available land in the new settlement areas.”

Security concerns are exacerbated by the camp's backlog in dealing with new arrivals. UNHCR reports a two-year backlog of more than 27,600 people waiting for their refugee status to be determined.

Opening a second camp would require more than $16 million, which UNHCR says it does not have available. Meanwhile, the agency reports, many refugees lack even the basics.

“Since the beginning of the year efforts to supply sufficient quantities of clean, safe drinking water have become a critical challenge with refugees now receiving less than the standard 20 litres of water per person per day.”

In an effort to recreate home life, populations from each country have divided into informal neighborhoods, so the Somalis, for instance, have their own markets and schools, in the Mogadishu neighborhood.

Reth Maker, a local teacher, was one of Sudan’s “lost boys” who came to the camp two decades ago, when he was just 5 or 6. He remembered how refugees would fight among themselves with machetes, describing it as a “hell life.”

As he spoke, a fight broke out between two young men in the street behind him. One appeared to be badly drunk and was knocked down. The drunk brushed himself off and began lurching around with a jagged piece of wood in his hand. The crowd watched him warily as the interview with Maker continued.

“Most of the people in camp you can see are trying to improve their lives,” said Maker. “But what can we do? We are refugees and we have no place to go.”

The refugees are not allowed to leave the camp grounds, which comprise 12 square kilometers. Many say they do not wish to integrate into Kenya but have the hope of returning home one day.

Maker teaches mathematics and English in one of the camp’s primary schools. He tries to give his students a message of hope, he said, using his own case as proof that it is possible to survive. He tells them that some lucky children even get repatriated to the United States, Australia or Europe. He hopes that might happen for him one day.

Meanwhile, he added, the idea of coming up with the traditional Sudanese dowry of 200 cattle for a wife is beyond hope, a further impediment to living a normal life.

Maker said that since he left Sudan as a little boy, he has not seen his parents.

“So I don’t know where they are at this time and that’s why I am still in the camp. And camp is just like my home now, you know?” he said.

As the sun set over the dusty landscape of sand and brush, a group of kids played an animated game of soccer near the entrance to the refugee camp. They ran excitedly across the dirt field, barefoot, clad in threadbare t-shirts. An older boy kicked a goal as a smaller child stood on the sideline, watching quietly.

Looming behind them was the main gate, where a sign reminds entrants to “leave the camp better than you found it.”

Sam Loewenberg is a Nieman Foundation Global Health Reporting Fellow at Harvard University, 2012. This article was reported with funding from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Research assistance provided by Laura Stilwell.

More from GlobalPost: Syrian refugees in Turkey tops 100,000

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?