Kenya election prompts fears of new violence

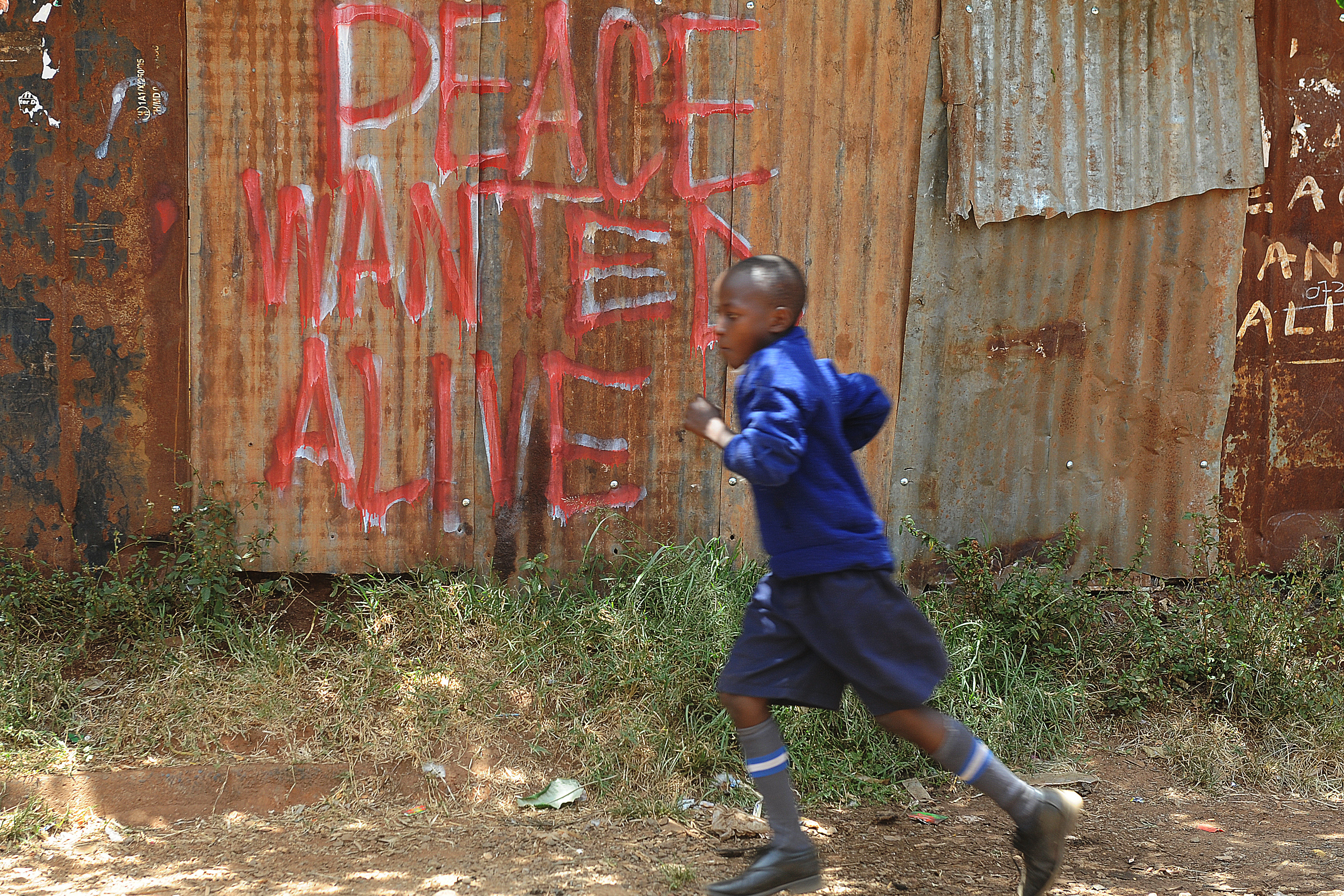

A schoolboy runs past a message urging for peaceful polls on Monday.

KIAMBAA, Kenya — Of all the terrible things that took place in the days and weeks following Kenya’s last election, the worst was the burning to death of 35 people in this village's small Pentecostal church.

After members of the Kikuyu ethnic group sought shelter there, hundreds of machete-wielding men from the rival Kalenjin tribe laid gasoline-soaked mattresses against the walls and set them alight.

Today, Kiambaa seems a bucolic place of birdsong, maize fields and tall fir trees. But memories of past killings remain fresh.

Peter Mwangi’s father and grandmother died in the massacre, which has come to epitomize the unbridled ambitions of Kenya’s political leaders. His two children, aged seven and 10, survived by slipping out of the burning building. Sitting under a tree near the rough wooden crosses that mark the graves of the dead at the church-turned-cemetery, the 34-year old Kikuyu farmer said nothing has changed since then.

“We don’t have time for the aggressors,” he said, waving a hand toward the tin-roofed homes of the village’s Kalenjin inhabitants — his neighbors and, Mwangi alleged, his family’s murderers. “They never ask us for forgiveness. Without that we cannot begin to go forward.”

Kenyans are still recovering from the violent election five years ago that killed more than 1,100 people and forced 600,000 from their homes. And there are fears of new clashes as the country prepares for another election on Monday.

Uhuru Kenyatta, the leading Kikuyu politician, is running neck and neck against his rival, Prime Minister Raila Odinga.

Violence is never far from the surface in Kenya’s dangerous democracy because political competition has a tribal hue. Ethnic bloodshed was a feature of the country’s first two multi-party elections in 1992 and 1997.

President Mwai Kibaki harnessed widespread optimism and hope to win a peaceful landslide in 2002, but his re-election in 2007 prompted the two months of politically motivated tribal clashes that threatened to tear the country apart.

That Kenya survived owes much to the intervention of outsiders led by former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan. Since then, Kenyans have voted for a new constitution that devolves power to the regions and seen the formation of a new electoral commission. The government has also made a slow start to a series of fundamental reforms to the judiciary, police and other institutions.

Still, after five years of a fractious coalition government, human rights groups and think-tanks are warning that the root sources of past election violence have yet to be tackled. They include disputes over land ownership, deep inequality, politicized ethnicity, rampant corruption and impunity for officials.

A recent report by New York-based Human Rights Watch said 447 people have been killed and 118,000 forced from their homes since last year by what it termed “inter-communal violence” that has flared in regions such as the Tana River on the humid coast and Samburu in the arid north.

There has been much talk of reconciliation in Kenya’s Rift Valley, where the worst of the violence spread in early 2008. A human rights activist in the town of Eldoret described peace building as “a growth industry, a commercial enterprise” — but one that’s had little impact so far.

“It is lies, there is no reconciliation, not for us here,” said Mwangi, whose father and grandmother died in the church blaze. He described his daily heartache of living amid the graves his dead family members and their alleged killers.

“If I could I would leave,” he said, “but this is my only land so what choice do I have?”

Nevertheless, like many here, Mwangi doesn’t expect violence to tear through the Rift Valley this time.

Although there’s been no compensation or reconciliation between Kikuyus and Kalenjins here, he believes a new police post — a collection of clapboard buildings with a Kenyan flag flying in front — will provide security.

There are larger reasons, too. Kenyatta, the leading Kikuyu politician, and his former rival William Ruto, the Kalenjin political boss, have agreed to run together for president and vice president. Their Jubilee Alliance seems to have papered over the deep cracks between their two communities.

“The only thing that makes me feel peace is possible at this election is the alliance,” said Joseph Githuku, whose 5 year-old son Samuel died in the church attack.

Keffa Magenyi, coordinator of the Internal Displacement Policy and Advocacy Center in the southern Rift Valley’s town of Nakuru, agreed the political deal may keep the peace in the short term, but said it fell well short of any kind of lasting solution.

“There are longstanding issues, historical grievances over land, resources and power-sharing, and deep seated hatred between Kikuyus and Kalenjins,” he said.

There are new complaints, too, including a government scheme to resettle displaced people that some complain favored Kikuyus.

“This resettlement is another time bomb for this country,” Magenyi warned.

Disputes over land ownership in the Rift Valley date back at least to the days of British colonial rule. White settlers displaced Kikuyus to seize the best farming land.

At independence 50 years ago, the Kikuyu elites who took charge of the government reclaimed much of the land for themselves. They also resettled poor, landless Kikuyus on traditionally Kalenjin land in the Rift Valley, setting the stage for decades of animosity and periodic violence betweeen the two groups.

While the Kenyatta-Ruto alliance, dubbed “UhuRuto” in their campaign, may have calmed relations between their supporters, it has also upset Kenya’s Western allies. Both men have been indicted by the International Criminal Court, the ICC, in the Hague, where they’re due to appear in August to stand trial for crimes against humanity committed during the 2007 violence.

Both insist they’re innocent and will clear their names. ICC Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda agreed this week to postpone the start of the trials by four months so they would not coincide with an expected run-off vote in early April if, as opinion polls suggest, there is no outright winner next week.

Prosecutors accuse Ruto of masterminding Kalenjin attacks on Kikuyus, including the one at Kiambaa, and Kenyatta of organizing retaliatory attacks by Kikuyu gangs on Kalenjins and Luos, the tribe of Ruto’s erstwhile ally Prime Minister Odinga.

One infamous revenge attack occurred in Naivasha, a low-slung dustbowl town in the Rift Valley that draws migrants from across Kenya to work in its huge greenhouses, which appear like blisters around the lakeshore, covering rows and rows of flowers and vegetables for export to Europe.

A gang of Kikuyus chased suspected members of the Luo tribe through the streets before setting fire to the building in which they took refuge. Nineteen died in the blaze. The building, in the poor Kabate neighbourhood, has been rebuilt. There are no crosses, no marker of the tragedy and no Luos still living in the area, locals said.

But there is rampant poverty. Sitting on a low crumbling wall across a garbage-strewn dirt road from the house in which the Luos died, four middle-aged Kikuyu laborers complained they could find no work.

“We’re skilled, but you see now we are seated here,” said one who agreed to be identified only by his nickname Whisper. “We have rent to pay, children at school, families to feed and no job.”

“Violence is because of poverty,” he continued as the others nodded in agreement. “Let us speak the truth. We are sitting here, no job. You have money, you give me 500 shillings [around $6] and tell me to attack this man, I will do it!”

More from GlobalPost: Kenya's chief justice 'threatened' over Kenyatta case

The 2007 post-election violence and the fear it has instilled is prompting a subtle balkanization that’s reversing years of gradual integration and intermingling.

As Monday’s polls approach, that process is accelerating, at least temporarily.

In Nakuru’s main bus park, a drinks vendor named Eric Omondi said a steady trickle of his fellow Luos were leaving town each day, heading to their western homeland. “People are being cautious,” he said.

But even as worries grow, hope for even some reconciliation endures. South of Eldoret in the hills surrounding the truckstop town of Burnt Forest, Mathew Kogo, a 66-year old Kalenjin repeated the view that the violence “doesn’t help any of us.”

“It made us realize that we all suffer,” he said.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!