How Colorado and Washington could end Mexico’s drug war

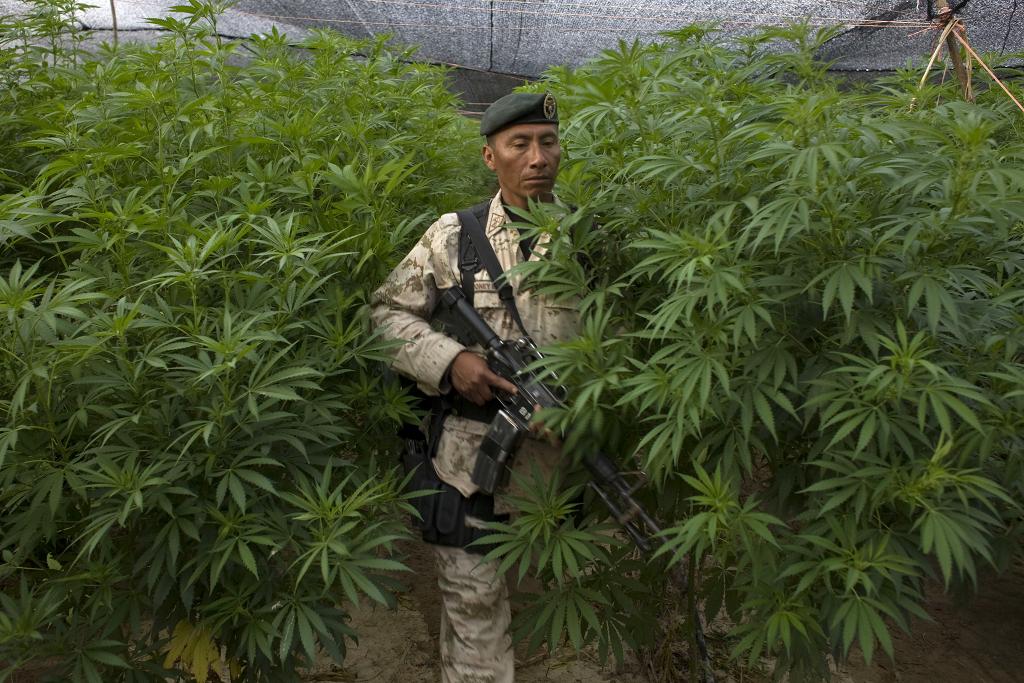

A Mexican soldier stands guard in a 300-acre marijuana plantation, the biggest found so far, in San Quintin, Baja California state, near the border with the US on July 15, 2011.

MEXICO CITY, Mexico — Might Americans' growing ability to get stoned without fear of arrest end Mexico's bloody gangster wars?

The legalization of recreational marijuana approved by voters Tuesday in Washington and Colorado could sap power from vicious smuggling gangs, and undermine the Mexican government's rationale for pressing on with the drug war, some analysts say.

The impact of the vote hinges on whether the state initiatives survive expected court challenges and continued enforcement of US federal drug laws.

But if they do — and legalization catches a wave across America — Mexico's narco-traffickers could lose up to 30 percent of the estimated $6.5 billion they earn annually from smuggling drugs, according to a study by the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness, a private think tank.

“We don't know how this is going to end, but we do believe that something big can happen,” contends Alejandro Hope, author of the study and a former senior crime analyst with Mexico's equivalent of the CIA. “The mere possibility is enough to continue closing following the election results and what comes afterward.”

At least initially, US federal officials' reaction to the legalization vote is unlikely to be friendly. President Barack Obama’s administration so far has rejected calls from across Latin America — including from former presidents of Mexico, Colombia and Brazil — for drug decriminalization as a means to crimp cartel profits and stop the gangland violence.

“It's worth discussing, but there is no way the Obama-Biden administration will change its policy,” Vice President Joe Biden said in a March visit to Mexico City. Apart from Congressional opposition to a policy shift, the US is party to international treaties that require drug enforcement.

But the legalization votes came just weeks before Mexico's own presidential transition. Enrique Pena Nieto, who takes office Dec. 1, has signaled that he wants to shift the anti-gangster campaign away from drug interdiction toward curbing the violent crime plaguing ordinary Mexicans.

Pena aides and allies argued that the Washington and Colorado results support that view, requiring a rethink of Mexico's militarized anti-narcotics campaign, which has claimed at least 60,000 lives, and perhaps far many more, in the past six years.

“We have to carry out a review of our joint policies in regard to drug trafficking and security in general,” Luis Videgaray, a senior Pena aide, told a Mexican radio interviewer following Tuesday's vote in the US. “This obliges us to rethink our relationship in regards to security. This is an unforeseen element.”

Meanwhile, a key border state governor and Pena ally has set the bar pretty high on any government drug policy reform planning.

“It seems to me that we should move to authorize exports,” Cesar Duarte, governor of gangster-plagued Chihuahua, which includes Ciudad Juarez, told Reuters in an interview. “We could therefore propose organizing production for export, and with it no longer being illegal, we would have control over a business which today is run by criminals. And which finances criminals.”

Despite booming pot production in California, Tennessee and other US states, Mexican marijuana still supplies about half the US market, according to the competitiveness institute study. Though lower than US marijuana in THC, the chemical that gives the weed its kick, Mexico's product is priced low enough to be competitive.

While a greater share of the gangs' profit comes from cocaine, heroin and methamphetamine — as well as kidnapping, extortion and other rackets — marijuana serves as a reliable bread and butter earner. An evaporating US market for Mexican marijuana would hit hardest the Sinaloa Cartel of Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, which earns as much as half its income from smuggled pot, Hope's study estimates.

But the Zetas, a powerful rival cartel that controls much of northeastern Mexico and the South Texas border, would also be slammed. With only limited connections to Colombian cocaine suppliers, the Zetas rely on pot smuggling for much of their income. Losing the marijuana trade could push the Zetas more deeply into extortion, kidnapping, human smuggling and piracy of movies, music and oil.

Before the Nov. 6 vote, 14 US states already had treated low-volume marijuana possession much like traffic violations. Others such as California and, in this latest vote, Massachusetts, have legalized marijuana use for medical purposes, which critics say is a backdoor way for recreational users to get the drug.

“This obligates us to think deeply the strategy we have to have in Mexico toward fighting this criminality,” Manlio Fabio Beltrones, the powerful head of the congressional caucus of Pena's Institutional Revolutionary Party, said following Colorado and Washington marijuana votes. “Above all when the principal consumer is liberating its use.”

GlobalPost series: Momentum is growing behind the movement to legalize it

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?