The horrors of eastern Congo

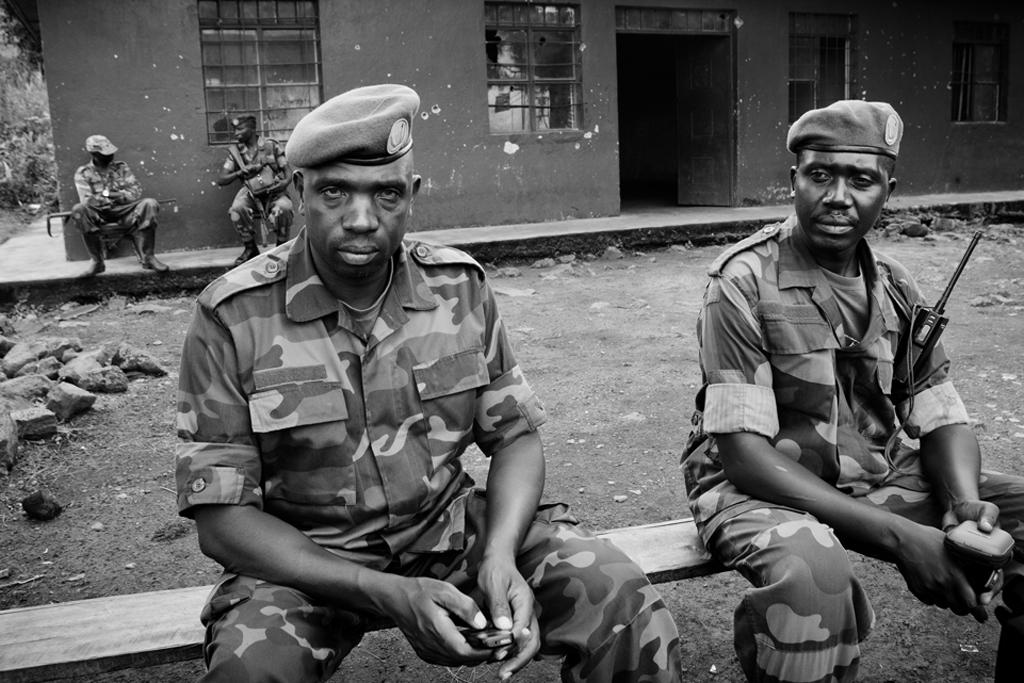

Col. Vianney Kazarama, an M23 rebel spokesman, in Rumangabo. The rebels are using a ranger headquarters in Virunga National Park as a training camp.

RUTSHURU, Democratic Republic of Congo — The figure in military fatigues and rubber boots stood on the rutted road, framed between green walls of tangled equatorial forest. He leveled his assault rifle at a small huddle of people kneeling in the mud next to their truck.

Around them were their scattered, meager belongings: burlap sacks of grain, cooking pots and small suitcases of clothes.

Attacks like this one, witnessed by GlobalPost on a drizzly Monday morning in October, are an increasingly common scene in the lawless east of the Democratic Republic of Congo, as security deteriorates in the wake of yet another rebellion that began last year.

Our Land Cruiser rounded a bend in the thick forest and slid to a halt a few dozen meters from the scene of the crime. Spotting us, one of the armed men signaled to the others — all bearing AK47s — and then began running in our direction.

Christian, the driver, muttered in Swahili as he ground the clutch trying to find reverse. Our guide Vincent shouted in a mix of Swahili and French. My eyes were fixed on the figure drawing closer, loping through puddles, gun swinging awkwardly in front of him.

Eastern Congo is crosshatched with armed groups that compete and coalesce with baffling fluidity. They fight each other, but reserve most of their depredations for civilians.

The latest rebellion began last April. It has so far forced hundreds of thousands to flee their homes, and triggered a new spasm of rape, child recruitment and murder.

Congo’s armed groups display a horrific capacity for brutality. Whether corrupt soldiers, rebel fighters, armed bandits, gangs of juju-peddling mystics, or members of any number of ethnically, regionally or politically defined militias, the men and boys with guns have turned eastern Congo into a byword for chaos.

Nowhere is this clearer than in North Kivu, an eastern province that abuts Rwanda and Uganda, nearly a thousand miles from the capital Kinshasa. It is a fertile territory of extravagantly folded hills, abundantly rich in minerals. And it is almost continually in crisis.

The wealth of coltan, tin, gold and diamonds beneath the earth fuel the fighting.

It also includes parts of Virunga National Park, Africa’s oldest nature reserve. Virunga is home to diverse landscapes and a vast array of animals, including hundreds of endangered mountain gorillas.

Virunga now faces the acute threat of insecurity, and the more chronic one of oil exploration — as western companies eye possible deposits beneath its lush slopes.

North Kivu is also home to a large and growing population of displaced people living in perpetual motion. They flee one insurrection after another, moving between temporary towns of makeshift shacks that sit on jagged, black volcanic rock.

When these people are on the move, they never know when they’ll be stopped, or by whom.

As the leader of the pack holding up the truck ran toward us, it became clear that he was just a boy; the assault rifle in his hands dwarfed him.

We sped backward down the road, clattering through puddles and potholes. The figure of the gunman receded as we careened around a corner, spun the car 180-degrees and headed in the opposite direction. As the panic subsided, Vincent broke into a falsetto rendition of a local pop song with the refrain, “I love my life!”

We had been lucky. The people on the truck in front had not. Driving away we passed three more trucks, loaded with goods and people, headed toward the ambush. We told them about the danger on the road ahead but the drivers only shrugged. It’s the only road south, what choice did they have?

A HISTORY OF INSECURITY

Insecurity has been woven into the fabric of North Kivu since at least the mid-1990s. It was then that the Hutu killers responsible for Rwanda’s genocide escaped across the western border into Congo. Two regional wars followed as Rwanda’s new Tutsi rulers sought to hunt down those responsible for the mass killings.

The first invasion overthrew the robber-president Mobutu Sese Seko. The second sought to oust his successor, Laurent Kabila, but failed.

In recent years, the conflicts have been more clandestine, with foreign nations backing local proxies rather than using their own invading armies. The combustible mix becomes explosive when combined with the region’s staggering natural wealth.

Rebellions frequently begin in North Kivu. The most recent one started nine months ago when army soldiers loyal to Bosco Ntaganda, a Tutsi Congolese general indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Court, staged a mutiny. With the alleged backing of Rwanda, Ntaganda set out to carve a fiefdom among the forests and hills bordering Virunga. The rebels called themselves of the March 23 Movement, or M23.

An uneasy detente between M23 and the Congolese army was broken in November when the rebels marched on Goma, the provincial capital, and occupied the city for close to two weeks before withdrawing.

M23’s military leadership consists of former members of the National Congress for the Defense of the People, known by its French acronym, CNDP. It’s a defunct rebel group, once led by another renegade Tutsi army officer, Laurent Nkunda, Ntaganda’s former boss.

According to UN investigators, the CNDP — like the M23 — enjoyed Rwanda’s backing during its 2008 rebellion. An agreement struck between the governments of Rwanda and Congo, however, led to the arrest of Nkunda. A related deal, signed on March 23, 2009, sought to integrate the CNDP fighters into the Congolese military. Instead, it gave the latest rebellion its name.

“The Congolese authorities pretended to integrate the CNDP into political institutions, while the rebel group pretended to integrate into the Congolese army,” said a recent briefing paper from the International Crisis Group, a Brussels-based think tank.

THE REBELS TRY TO GOVERN

Inside the territory it now controls in North Kivu, the M23 rebels are busy establishing the trappings of a state as they seek to re-invent their armed rebellion as a broad-based political movement. There are civilian administrators and ministries of health, education, justice, even environment and tourism.

The rebel capital is Rutshuru, an orderly hillside town with a main road bordered by tall trees. Teams of street sweepers keep the place clean. Rebel soldiers maintain security.

Benjamin Mbonimpa is the town’s administrator. He calls himself “the eyes and ears of the executive,” referring to the M23 top leadership: military commander Col. Sultani Makenga and political leader Jean-Marie Runiga.

At Mbonimpa’s office, two military men sat and listened. The taller of the two, folded into his chair so that his knees were higher than his waist, was Seko Nkunda, younger brother to Laurent, the ousted former head of the CNDP. Mbonimpa said he used to be the CNDP’s foreign minister.

Mbonimpa has taken over his predecessor’s abandoned office, including his desktop computer. A large Congolese flag hangs from a pole behind his swivel chair. He is proud of the M23’s achievements.

“The only government services we have not replaced are the taxes,” he said proudly.

“The governor of North Kivu was in charge of taxes and it all went into his pocket,” Mbonimpa claimed as he motioned the pocketing of a fistful of cash, “his, and [President Joseph] Kabila’s.”

The rebellion’s own funding appears to come mostly from levies charged at checkpoints on the roads and from control of the Bunagana border post with Uganda, where goods entering and leaving the country are taxed. The United Nations says the two sources yield $200,000 a month.

M23 leaders, however, deny they are seeking an independent state.

“What we want is to change the Congolese leadership. It is weak, corrupt. We are Congolese, we don’t need to be autonomous,” Mbonimpa said, clutching the national flag at his side for emphasis.

“Kinshasa may be 1,000 miles away, but a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step,” he added.

Mbonimpa said his priorities in Rutshuru were security, development and fighting corruption, in that order. To this latter end, a handful of M23-branded signboards — the “M23” painted in black and blue above a Nike-style red swoosh — declare, “We are against corruption”, in block capitals in French, English and Swahili.

As if the signboards might on their own end graft, Mbonimpa said: “You have seen our signs. It is not like before!”

Privately, local residents dispute Mbonimpa’s claims of altruistic governance. They say the rebel ministries are hollow institutions, their services non-existent and their authority rooted in fear.

“The government did nothing, M23 does nothing. It’s the same thing,” said a middle-aged laborer who did not want to give his name. “You ask about ‘the government of the M23’ and I don’t know what you mean.”

“Whether it is the Congo government or the M23, nobody takes responsibility,” said a medical worker, who also asked to remain anonymous. He pointed, however, to a pervasive uneasiness in rebel controlled zones. “Under the previous government, we could do what we wanted, now we are more careful.”

Human Rights Watch and others have documented a series of brutal and violent attacks, including dozens of cases of rape and murders that it says were perpetrated by M23 fighters in Rutshuru and Goma.

The New York-based group has also accused M23 of forcibly recruiting children and young men into its ranks. In an interview, M23 spokesman Col. Vianney Kazarama dismissed the allegations with a broad smile.

He insisted that women were safe in rebel territory, no one was murdered and that any and all recruits were volunteers.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!