Egypt: For Coptic Christians, Christmas comes with fear this year

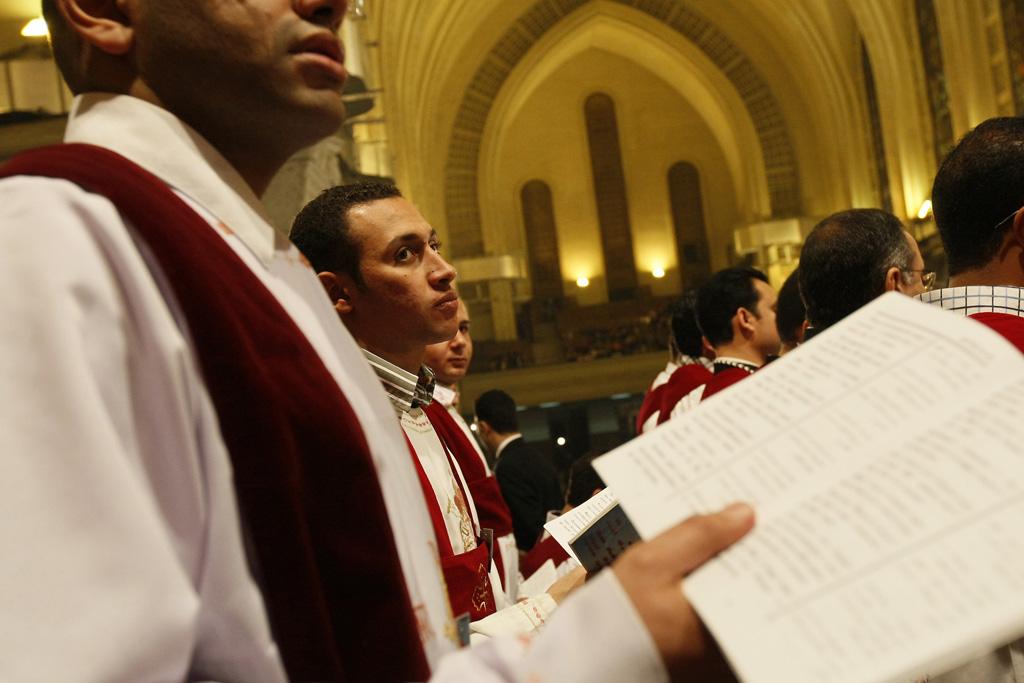

Egyptian Coptic Christian choir members get ready for Christmas midnight mass in Abassiya Cathedral in Cairo on Jan. 6, 2011.

IMBABA and SANHOUR, Egypt — Salah Aziz won't get to celebrate Christmas this year.

This week marks Coptic Christmas, traditionally a time for family and festivity. But last April, extremist Salafi Islamists slit Aziz’s throat and set his body alight along with the St. Mary’s Church he guarded in this historically volatile Cairo neighborhood, church officials said.

Aziz's brutal murder is evidence of the Coptic Orthodox Christian minority's increasingly precarious place in Egyptian society.

Longtime victims of discrimination, the region's largest Christian population worries that the situation under a new Muslim Brotherhood-led government is getting worse. The Brotherhood, say many Copts, pays lip service to religious freedom while engaging in its own sectarian rhetoric.

Last month, voters approved an Islamist-slanted constitution that, while granting Christians the right to build “houses of worship,” was written without input from the church.

“The constitution is very bad. It was forced on us, on the Christians and on others,” said 26-year-old Amir Fikri, a youth trainer at the St. Mary’s.

“We need a miracle to end the tensions [between Muslims and Christians],” he said, adding that many of his own friends have already emigrated from Egypt because of the deteriorating situation. “It’s getting worse every day.”

Copts fear Egypt's new establishment will do little to curb rising extremist assaults on Christian communities and institutions like the one that killed Aziz.

As Copts filed into the newly rebuilt St. Mary’s Church for midnight mass services Sunday night — marking their Christmas Eve amid swirls of sweet incense and low, chanted hymns — the mood was bittersweet. Congregants say they won’t celebrate Christmas publicly in the streets for fear of reprisals from emboldened vigilante Islamists.

“We are careful so that we do not subject people to any harm,” said Dr. Yusuf Al Komos, a Christian pathologist in the capital.

Egypt’s roughly 8-10 million Christians — there is no official count — trace their origins to Egypt before the birth of Islam in the seventh century.

Sectarian violence has long been a part of Egypt’s modern religious landscape, tracing back to the military dictatorship of Gamal Abdel Nasser in the 1950s. Under the regime former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, Christians largely withdrew from public life, suffering discrimination and lengthy bureaucratic procedures to obtain licenses to build churches.

Despite the bigotry of the Mubarak era, many Christians viewed the ostensibly secular dictator as a bulwark against a rising tide of homegrown Islamism.

“It was better before the revolution. The religious political stream always oppresses people,” said 45-year-old Hanna Salib, a local sculptor and Christian resident of Sanhour, a village about 75 miles south of Cairo in the verdant Fayoum province.

“The revolution replaced the tyranny of [Mubarak’s] National Democratic Party with more oppressive parties,” he said.

On Sunday, Egyptian president and former Muslim Brotherhood leader, Mohamed Morsi, sent Christmas greetings to the newly elected Pope Tawadros II.

He did not attend mass at the national cathedral in central Cairo, instead dispatching his chief of staff. But the Brotherhood’s ruling Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) says they have worked hard in the post-revolution period to safeguard Christians’ rights.

Video from GlobalPost: In Cairo, Christians mark faith with tattoo

“All Christians are Egyptians. We do not look at people as Christians and as Muslims,” said former FJP parliamentarian in Fayoum, Hamdy Taha. “Unity is a must, a cornerstone of building the modern Egyptian state. Rights and duties for the country are built on the basis of citizenship, not on religion.”

Also in Fayoum, the ultra-conservative Salafi Al Nour Party says Muslims and Christians live together peacefully, like they have for years.

“We have been dealing with each other for years,” said Al Nour’s secretary-general in Fayoum, Mohamed Abu Taweb. “If there was any oppression, they [the Christians], would be alienated. But they live here in peace, with their churches.”

Copts in Fayoum’s Sanhour village, which hosts the largest Christian population in the area, says there have been no direct confrontations or attacks — but the mood is tense.

“The level now is calm. But the future is what we worry about,” said 53-year-old Magdi, an education administrator in Sanhour. He did not want to use his full name for fear of retribution from security forces or local extremists, he said.

Elsewhere in the country and over the past year, Copts have been expelled from their homes, intimidated on election days, and imprisoned for “insulting Islam.”

During unrest in Cairo over the constitution last month, Brotherhood leader and constituent assembly member, Mohamed El Beltagi, said the majority of protesters outside Morsi’s presidential palace were Christian.

The comments have inspired little trust in the dwindling and already fearful Coptic community.

“Extremism is stronger these days, it’s everywhere now — in the schools and in the streets,” said 47-year-old Mariam Gabriel, a member of the congregation who has lived in the vicinity of St. Mary’s for more than 40 years.

When asked what there was to celebrate for Christmas this year, she said: “Our neighbors don’t congratulate us on Christmas anymore. We place our hope only in God.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!