A Daughter’s Journey, Part VI: Reflection and Closure

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa — “Let’s hope they show up,” the doctor said, as I waited in the patient examination room at the Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital’s Perinatal HIV Research Unit.

It was exactly where I had been sitting 10 days earlier, the day I arrived in South Africa. I’d returned to the unit to speak with a HIV-positive mother and daughter. They were already 30 minutes late.

“Do you think they will come?” I asked the doctor.

She shook her head, with a disappointed look on her face. The pair had only agreed to speak with me if I promised not to take pictures or use their names, and now it looked like they may not speak with me at all.

Fifteen minutes later, a petite young woman walked through the door. A knit hat, which matched her periwinkle eye shadow, covered her short hair and framed her thin face.

She was followed closely by her mother, who wore a red Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) t-shirt and had dreadlocked hair pulled into a ponytail. Both looked skeptical of me as I sat opposite them, with a small table between us.

I asked the daughter if there was anything she felt was important to share about growing up with HIV, just as I had asked Christina Rodriguez—the other born HIV-positive daughter I spoke with—in New York.

“It’s better when my mom starts,” she told me shyly.

She looked to her mom who leaned back in her chair and gave a slight laugh.

“It’s a difficult thing to live with knowing that there is no cure, first of all, and that there are some things that you cannot do that you wanted to do,” she began.

The mother described not being able to get certain kinds of insurance, difficulties with having relationships, and most notably, her struggle with disclosing her status to others.

After she told her sister she was HIV-positive, she noticed that other people in the neighborhood knew. Her sister had turned her status into community gossip. And though the community did not ostracize her, they assumed she had AIDS and would die, she said. After that experience, she felt she couldn’t trust anyone.

She assured me that she would not tell anyone other than her mother, siblings, and her two oldest children—one of whom is negative. She had not told her 13-year-old son, for fear that he was not mature enough to handle the news.

“In this world, I believe that you don’t trust people,” she said. “A friend can be a friend, maybe a best friend, who you disclose to. The next day you may have an argument and disagree and she will go and tell other people,” she said, looking at her daughter.

I asked when and how she told her daughter she was positive. Had she only told her because they were both positive? How could she trust her young children when she couldn’t even trust her own sister?

The daughter remembered the day her mother told her that they were both positive. She was washing dishes with her mom. She was thirteen, and although she had been taking HIV medication since she was diagnosed at five years old, she did not know that she had the virus. She thought she was taking medication for her asthma.

“Do you know why you take all of this medication?” her mom had asked her.

Then her mom told her it wasn’t for her asthma.

“Why me?” is all she can remember thinking.

On the outside, her life didn’t change. She continued to take her medicine and she felt healthy. But now she had a secret, and she was angry. She was angry with her mom for not telling her, and angry that this had happened. At school, she remembers, although HIV and sex education were addressed in the curriculum, her peers made jokes about AIDS.

“I wanted to tell them they were wrong,” she said, but she could not tell her friends that she was an example of someone HIV-positive who was healthy and normal, because she would have to disclose her status. She didn’t want to be gossiped about.

Now, at 22, she struggles with a similar problem. She said she wishes she could tell her sexually active friends to use condoms and to not sleep around, but she still cannot bring herself to share her status. She has only told her family, and other people who are HIV positive, whom she mentors at the Perinatal HIV Research Unit where we were sitting.

More from GlobalPost: VIDEO: Closure and Reflections from South Africa

As I spoke to this young woman, I thought about Christina, who I met in New York City. Their stories were so similar, both were the only of three children in their families to be born HIV-positive. Both of their mothers contracted the virus from their husbands and struggled with how much their daughters should know. Both are roughly the same age and making their way through university. And both have found peace and strength in mentoring other young people with HIV. Though half a world apart, their stories and their struggles were fundamentally the same.

If I had been born with HIV, my story would have been the same, too. Before I took this journey, I thought my mom was different than other AIDS victims, because she did not fit what at the time of her diagnosis was the profile of someone who had HIV. Her father was a doctor and she had received the best education. She was married, held a stable job, she was straight, and she was not an IV drug user. But it turns out that class, race, education level, and nationality don’t protect anyone from this epidemic.

If I had been born positive, I wonder how I would have chosen to handle my own secret. Would I have been ashamed to be associated with the stereotypes and not tell anyone, like the young woman sitting across from me? Or would I be able to be open with my friends without fear of stigma, like Christina? I don’t know the answer.

Despite different backgrounds, these mothers, too—including mine—have all shared the same fears, questions, and struggles. And each choice they have made about how to cope with their status has hinged on one thing: how to be a good mother.

“You look up to your mom don’t you?” I asked the young lady before leaving.

“Yes,” she said with a warm smile. “She is my inspiration.”

I smiled and thought to myself, My mom is mine too.

In fact, my mom is the whole reason I took this journey to begin with. But I kept the thought to myself, because this interview was about her story, not mine.

As my time in South Africa ends, I prepare to head back to the States where I will cover the International AIDS Conference in Washington, DC. I will bring with me the stories of the women I have met in South Africa, and the lessons I believe we can learn from how communities in Cape Town and Johannesburg cope with HIV/AIDS.

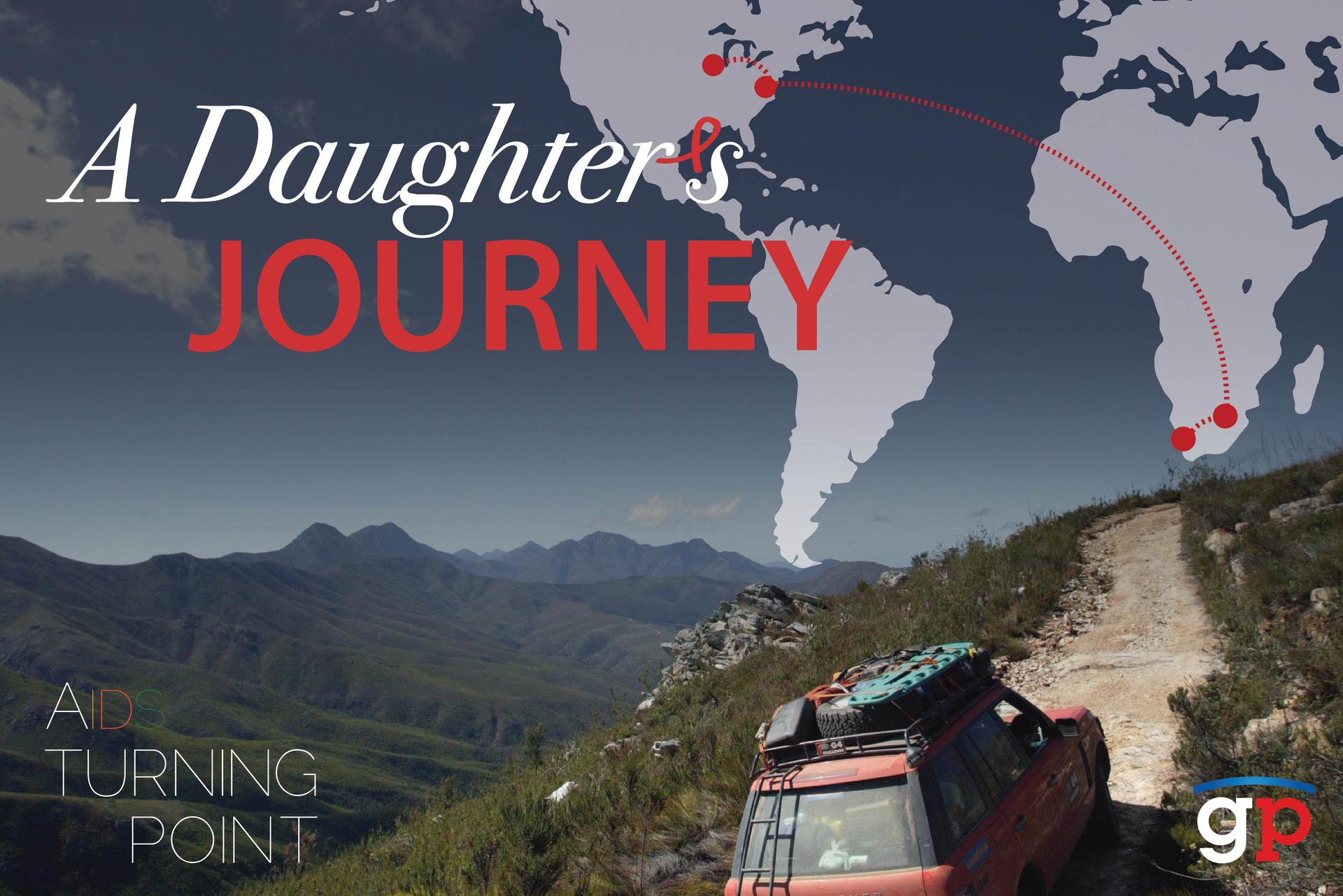

“A Daughter's Journey" is a series of blog posts by Tracy Jarrett, a GlobalPost/Kaiser Family Foundation global health reporting fellow. Tracy is traveling from her hometown, Chicago, to Cape Town, South Africa as part of a Special Report entitled "AIDS: A Turning Point.” Read Parts I, II, III, IV, and V of Tracy's journey on GlobalPost.