Brazil: An end to dirty politics as usual?

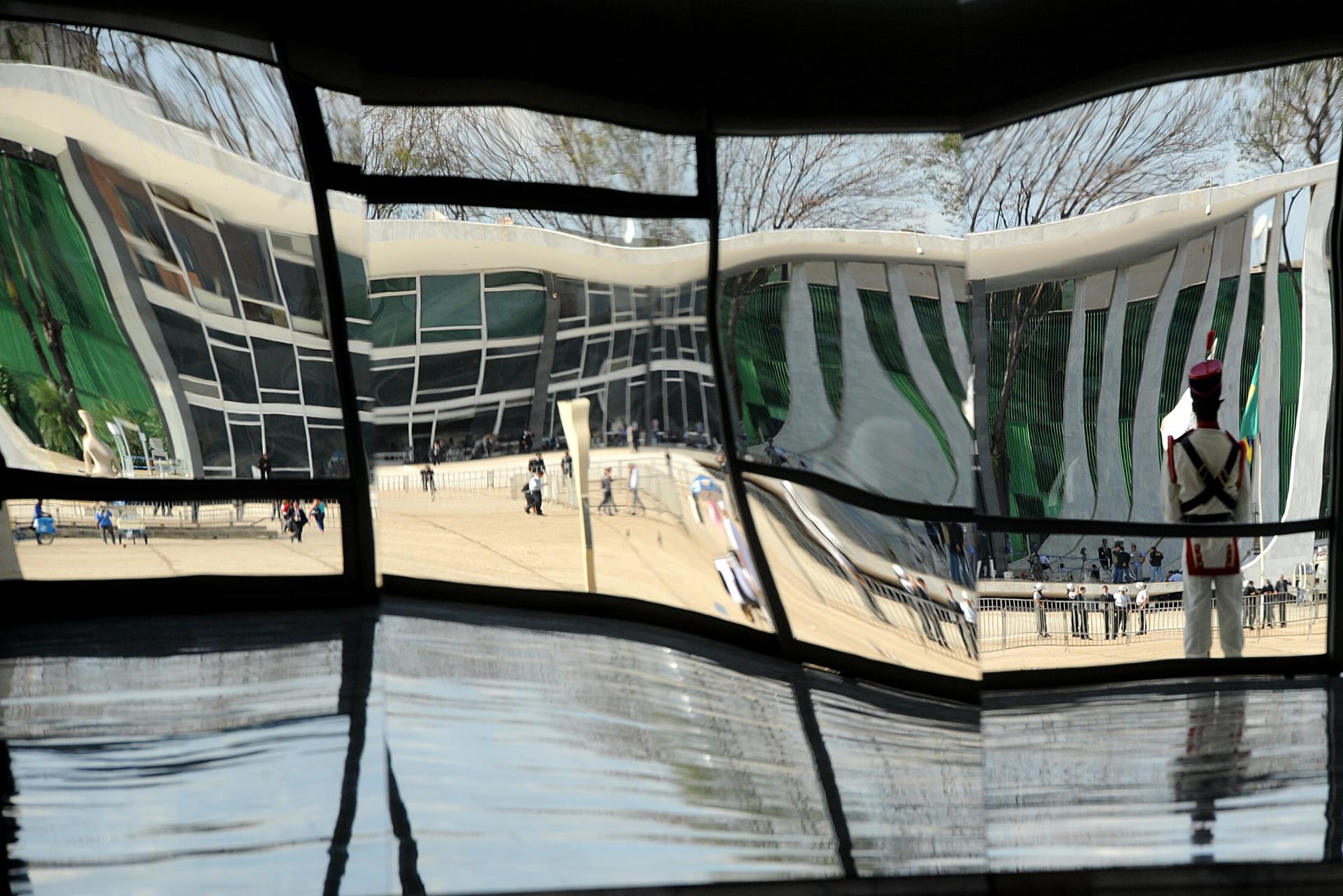

Brazil’s Supreme Court building seen through the warped reflection of the Planalto presidential palace in Brasilia.

BRASILIA, Brazil — Over the past few months, strange things have been afoot in Brazil.

Ordinary Brazilians have been gripped nightly by complex corruption trials. Carnival masks have been fashioned in the likeness of a staid and somber judge, rather than the usual glossy celebrity.

And, most shockingly, elite politicians have been handed prison sentences for graft.

A massive vote-buying corruption trial known as the “mensalao” (big monthly stipend), dating from the administration of former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, has shaken things up.

“I thought this case was going to end up as all the early ones did: ‘acabar em pizza,’” or ‘finishing with pizza,’ said Felipe Rosado, an economics student at the University of Sao Paulo. “This is an expression we use for when wrongdoing is found but nothing is done.”

That Brazilians have a phrase expressing impunity for political corruption should hint at how ingrained it is here.

Brazil, after all, is where President Fernando Collor de Mello was impeached for corruption, in 1992, only to return as a senator 11 years later. Sao Paulo’s former mayor and governor, Paulo Maluf — endlessly accused of corruption — was just as endlessly re-elected, earning him the inglorious tagline “he steals, but he gets things done.”

Conservative estimates put the annual cost of corruption here at a hefty 2 percent of gross domestic product — about as much as the government spends on new infrastructure. Foreigners doing business in Brazil complain of the “Brazil cost” — an extra levy of Kafkaesque bureaucracy, high taxes and corruption.

But things, it seems, are changing. Brazil, mindful of the attention it is receiving ahead of the World Cup and the Olympics, and keen to become a more powerful player on the world stage, is cleaning up its act.

Dilma Rousseff’s presidency thus far has been a whirlwind of anti-corruption, pro-transparency moves: There have been laws to tackle money laundering and to prevent candidates with criminal records for running for office. Six ministers were ousted over graft within her first year in office — earning her a 7-point bump in opinion polls — and she has launched a new freedom of information law, an open-data portal and a truth commission to investigate the military dictatorship.

“Dilma has done more for transparency in Brazil than all other presidents combined,” says Greg Michener, a political scientist specializing in transparency at the Fundacao Getulio Vargas in Rio de Janeiro.

Dilma — a consummate pragmatist, universally referred to by first name — is not only seeking to alleviate corruption’s economic drag, but also to help secure her geopolitical ambitions as a global player, Michener says.

“Geopolitical prominence rests on Brazil’s reputation — it can’t rest on the strength of its economy or its armaments,” says Michener. “With increased transparency you have signaled a commitment to govern decently.”

Optimism, although warranted, should be cautious, experts say. Even as the last defendants in the mensalao case were receiving sentences Wednesday, another corruption case uncomfortably close to ex-President Lula was making headlines.

His former assistant, Rosemary Novoa de Noronha, stands accused of running an influence-peddling gang that sold government approvals for cash and gifts including, reportedly, cruise vacations and plastic surgery. Brazil’s media have come to call the case “Rosegate.”

While the fact the Supreme Court has handed down sentences at all is a significant breakthrough in a country where political accountability can usually be offset by a fat wallet, the heralding of a new era might be premature, according to David Fleischer, professor emeritus of political science at the University of Brasilia.

“It’s a game changer in that it’s a signal that impunity is no longer the way things are done,” said Fleischer. “But we have a very complicated and dysfunctional judicial system, and there is still doubt about how long those convicted will actually serve.”

The judicial system in Brazil is famously labyrinthine and weighted toward the wealthy and powerful. It allows for seemingly limitless appeals to be filed, and a criminal cannot be jailed until the final appeal has been rejected. With a good lawyer, this can take years.

Moreover, elected officials benefit from an archaic immunity, which means that only the Supreme Court can try them. And while 10 years might sound like a long jail term, Brazilian sentences can be commuted by as much as five-sixths.

Due to a quirk of the Brazilian system, some of those convicted could even end up keeping their jobs as congressmen while on partial parole.

“They could attend daytime sessions in the Chamber of Deputies, but not nighttime sessions,” laughed Fleischer. “It’s crazy, but that’s Brazil.”

Some Brazilian citizens have expressed disappointment that the sentences weren’t longer.

“Ten years isn’t enough for Jose Dirceu, and he’ll be out in two,” said Orlando Augusto, a driver in Brasilia, referring to Lula’s former chief of staff and the mastermind of the scheme. “Corruption is a cancer on our country, destroying everything from the inside. He should have got 30 at least.”

People might be disappointed, said Michener, but their increased awareness is itself a sign of a turned corner. The case has played out as something of soap opera here, attracting an unprecedented amount of attention from the middle class. Live footage of the trial has been shown nightly on television, and has made a star of Joaquim Barbosa, a bricklayer’s son who is the first black head of the Supreme Court. Carnival masks have even been made in his likeness.

“Barbosa is wonderful,” said Neide Moura de Brito do Nascimento, a cleaner from Brasilia. “He is committed to the masses and with corruption he is just and forceful.”

Fabiano Angelica of Transparencia Brasil says that decreasing tolerance for graft is inherently connected with the growth of the middle class here, which has swelled by more than 30 million in recent years to include some 52 percent of the population.

“As the average Brazilian reaches a better economic situation and a few more years of school, he or she starts pressuring for reforms and for a more effective and less corrupt government.”

If President Rousseff’s moves toward transparency are an attempt to win over this increasingly scandal-intolerant group, they are working: Her approval rating is holding steady at a sky-high 77 percent, according to one recent poll, despite slowing economic growth. The mensalao may even benefit her, Michener says.

“Many people just perceive that justice is happening under this government,” he said. “Of course Dilma has nothing to do with it, [the Supreme Court] is not influenced by the executive branch, but a lot of people don’t understand that so she will benefit from it.”

Lula may not survive another scandal untarnished, but for some here, in grooming Dilma as his successor, he did one thing right in the fight against corruption.

“Lula is the most corrupt of them all,” said Augusto, the driver in Brasilia. “But Dilma is different. We trust her.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!