Argentina: Remembering Evita (PHOTOS)

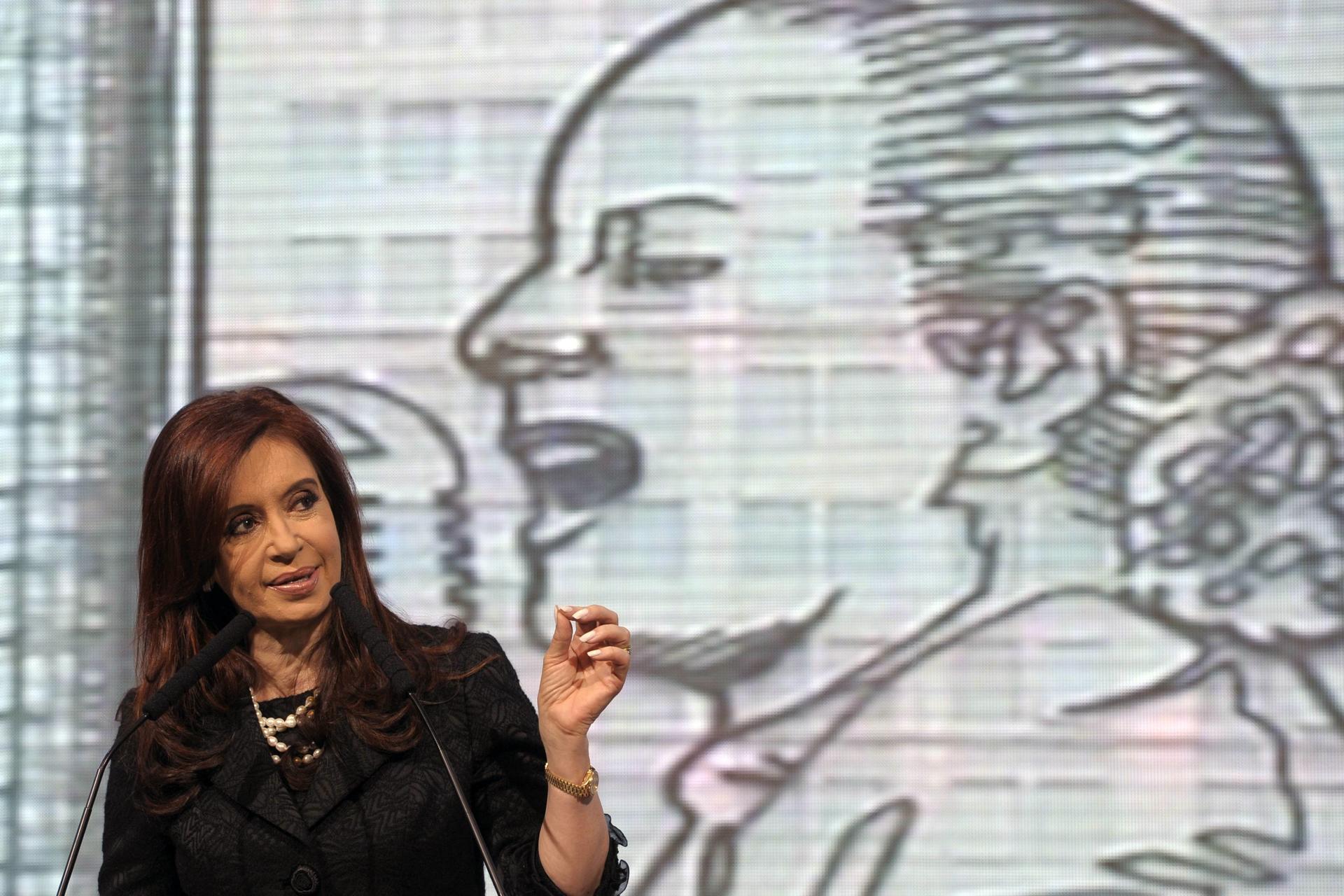

Argentine President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner delivers a speech after the unveiling of a steel sculpture of iconic first lady Eva Peron in the northern facade of the Social Development Ministry.

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina — Sixty years ago today, Argentina fell into mourning. The country’s adored and charismatic first lady, Eva Peron, died at just 33, following a battle with cancer.

A radio announcement informed the nation its “spiritual leader” had passed away. More than 2 million people followed Peron’s funeral procession through Buenos Aires as flowers rained down from the city’s balconies.

Peron, who is fondly referred to as Evita, was first lady from 1946 to 1952. Her legacy, however, lives on. She was a heroine of the working classes who fought for social justice and women’s rights.

“Eva stood out for her love of the people,” says Araceli Bellotta, author of “Eva Peron: Champion of the Humble.”

“No public figure or politician since has ever matched her,” she said. But many have tried. One former president, the neoliberal Carlos Menem, is derided by the very sections of society Evita helped, despite exploiting her image in his election campaign.

The current president, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, has come closest to emulating her, Bellotta says.

“Eva is more present than ever under Cristina’s administration,” said Dante Gullo, a lawmaker in the Buenos Aires city government. (Argentines often refer to their president by her first name.)

More from GlobalPost: Argentina: ditching the dollar

During Fernandez’s speeches at the presidential palace, an image of Evita is displayed in the background — purposefully juxtaposing the two. At pro-government rallies, flags bearing the faces of Eva and her husband, President Juan Peron, are held up alongside those of Cristina and her late husband, Nestor Kirchner. Like Evita, Fernandez is glamorous, and a compelling public speaker.

At the Social Development Ministry building in the heart of Buenos Aires, Fernandez’s government commissioned two 100-foot high iron murals of Evita.

Her policies have also brought strong comparisons with Evita.

“Cristina has picked up Eva’s baton,” Bellotta told GlobalPost. “She’s institutionalized Eva’s ideology [of equality].”

Fernandez has spent generously on welfare programs — including a universal child benefit scheme — while Evita is renowned for the work she put into her charitable foundation, which funded projects for the poor.

Evita also supported women’s suffrage — granted in 1947 — and created a female affiliate of the Peronist party founded by her husband.

In doing so, she opened the door of Argentine politics to thousands of women. Fifty-five years after her death, in 2007, Fernandez became the country’s first female president.

Together with her predecessor, Nestor Kirchner, Fernandez has revived the left wing of the Peronist party — pursuing policies aligned with those of three-time President Peron, a champion of labor rights.

“There are political similarities,” says Leandro Bullor, an economic historian at the University of Buenos Aires. “[The Kirchners] restructured the original Peronist model for the 21st century.”

But the symbol of Evita transcends politics, according to Alejandro Marmo, the artist and sculptor who designed the giant murals.

“She is a cultural icon,” Marmo told GlobalPost. “Eva is recognized for her love, commitment and fight. She awakened the hope of the people.”

Born Eva Duarte in May 1919, she had a humble upbringing in the small town of Junin before moving to the capital as a 15-year-old to pursue a career as an actress.

Evita arrived in Buenos Aires at the height of a migration wave from rural provinces.

The migrants — pejoratively called “cabecitas negras,” or black heads, because of their darker skin — formed Argentina’s working class during a period of industrialization in the 1940s and became the social base of Peronism.

In 1944, she met Peron, then labor secretary, during a fundraiser for the victims of an earthquake that had devastated the city of San Juan.

Evita campaigned fiercely during her husband’s successful presidential bid of 1946. She also supported his politics through her foundation, which donated thousands of sewing machines, clothes and cooking pots to poor families and built Evita City, a neighborhood of 15,000 homes.

More from GlobalPost: Argentina: I was stolen and raised by the regime

“Eva carried out her work in person, which made her the link between Peron and the people,” says Bullor.

In 1951, she considered running for the vice presidency and addressed the “Cabildo Abierto,” a rally of 2 million people who supported the Juan and Eva Peron joint ticket.

By then, however, she was already suffering from cervical cancer. Evita died July 26, 1952, just a month after Peron was re-elected.

Her embalmed body was put on display to the public, but went missing for 16 years after Peron was overthrown in a 1955 military coup. It now rests in Buenos Aires’ Recoleta cemetery.

Today, Eva is a mythical figure appreciated worldwide.

Her life was the subject of the musical “Evita,” which made a return to Broadway this year and features the popular song “Don’t cry for me Argentina.” In the 1996 film adaptation, Madonna played the leading role.

The 60th anniversary of her death has been commemorated in Argentina with Eva Peron Week at the Buenos Aires legislature where her foundation was based.

A limited edition of the 100 peso bill bearing her face has also been printed. Tonight, Kirchnerist movements will hold a torch-lit march to her tomb.

“Eva did so much in such a small amount of time,” says Bellotta, the author. “She was beautiful and died young, which adds to the legend.”

As a cultural icon, comparisons are made with Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the Argentine guerrilla who fought alongside Fidel Castro during the Cuban Revolution before he was murdered in Bolivia, age 39.

And like Guevara, Evita is a controversial figure. “She divided Argentina,” says Bullor. “She clashed with the oligarchy and demanded workers stay loyal to Peronism, some of whose methods were undemocratic.”

President Peron, for example, denied unions the right to strike in the 1949 Constitution. He is branded a demagogue by anti-Peronists, who tar Evita with the same brush.

“History will remember her as an emblem of the struggle for equality,” Marmo, the artist, says.

“My love for the people is the only thing that moves me,” Evita proclaimed in her final speech to the “descamisados,” or the shirtless, the name she used for the working class. “The happiness of just one descamisado is worth more than my life.”

The iron murals that the Fernandez administration commissioned in Buenos Aires reflect that split opinion.

The image that faces the affluent northern neighborhoods depicts Eva as combative and aggressive. In the other, which points to the poorer south, she is smiling and calm.

Fernandez won a second term last October with the biggest margin of victory since Peron’s third election in 1973. But she, too, divides Argentina, where people are either for or against the Kirchnerist project. “There’s no center ground,” says Bullor.

The middle class has turned against Fernandez because of soaring inflation, and what they view as short-term, populist policies and an attack on the free press. The working class, however, continues to back her. Says Bellotta: “Like Evita, she's opened up opportunities for the poor.”

More from GlobalPost: The Argentine economy's fuzzy math problem

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?