An American in Paris dies

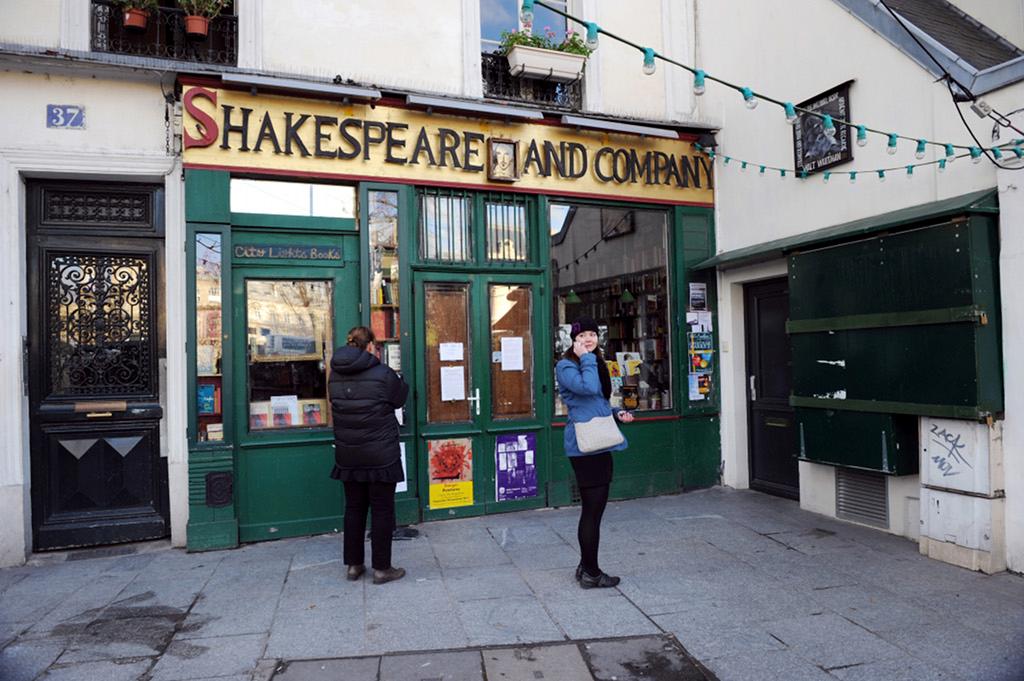

Shakespeare and Company, Paris landmark for generations of Americans.

George Whitman has died. He was 98.

You may not know his name but if you speak English and have ever visited Paris you probably know his bookshop: Shakespeare & Co.

Whitman set up the shop in 1951. He was one of a generation of Americans – mostly ex GI's on the GI bill – who went to Paris after World War II and tried to re-start the party that made the French capital the center of western culture in the 20's and 30's, the place where the Hemingway and Fitzgerald legends were born.

The Paris Review was started. William Styron, Norman Mailer, James Jones, George Plimpton, humorist Art Buchwald and jazz musicians too numerous to mention moved back. There were so many Americans in the city that M-G-M made a Gene Kelly musical about ex-patriot life called "An American in Paris" the year Whitman opened his shop. It won the Best Picture Oscar.

By the mid-1950's though it was clear the party was over and New York was the place where cutting edge culture was being created. Paris was something of a perfectly preserved museum of an era comprehensively demolished by war. Most of the ex-pats headed home.

George Whitman stuck it out. In the golden days of Paris there had been an English language bookshop called Shakespeare and Company. It was run by an American woman named Sylvia Beach. It was more than a place to sell books. Beach was a patron of writers, most famously James Joyce. She effectively edited and published Ulysses. But her shop had not survived the disruption of the war.

Whitman decided to open a used bookstore and called his establishment Shakespeare and Company in memory of Beach's store (and perhaps to trade in a little on her legend).

It was set on the tiny Rue de la Bucherie with an unobstructed view towards Notre Dame. It became a clubhouse for the millions passing through. A rainy day in Paris could be waited out reading in a corner of the shop. A student whose money had run out and couldn't afford to while away an afternoon over a few beers in a cafe could hang out for hours without hassle.

Whitman sat by the cash register in the middle of the downstairs area amid the clutter of his massive stock of books – some in good condition, most bearing the signs of wear and tear from having been passed around by many readers.

He would engage in book talk and dispense travel advice: willingly to pretty young women, in a more surly tone to young men or the more bumptious tourists.

By the time I made my first visits there 40 years ago, the bookshop was an anchor of Paris life and Whitman a well-established character: wizened, missing his front teeth, their absence highlighted by his wispy goatee. He could be alternately charming and rude.

To me he was mostly rude. There was a young woman I met there, one of the many he flirted with, and we used to entwine ourselves in the upstairs front room. Nothing pornographic, just two students kissing fervently, playing our parts in the imaginary film of being young artists in Paris, a film with ten million versions that unspool in the minds of people from 16 to 98 who have grown up on the romance of Paris's past. (Woody Allen's version of his fantasy, Midnight in Paris, is currently in the cinema.) He was a jealous old guy and took to noisily shutting up the shop whenever I dropped in and asked after the girl. He would re-open as soon as I turned the corner and headed up the Rue St. Jacques.

There were others who passed through. Years later, during the war to overthrow Saddam, I met the Iraqi Kurdish man who became my translator. He recounted the story of his one brief visit to Paris in the early 1970's and how he had gone to the English language bookstore and met the very odd man who ran the place. It was at Shakespeare and Company that he found a used copy of The Portable Faulkner. The reason I hired him to be my translator was that when I interviewed him we spent most of the time talking about Faulkner. It was not a conversation I expected to have in Erbil the night before the war started.

When Ahmad Shawkat was murdered five months after Saddam was overthrown, I wrote a book about his life and included his visit to Shakespeare and Company.

As the decades have gone by, my relationship to Paris has changed. I don't buy the myths of the past and enjoy the city for its relationship to the present, specifically, who I am in the present.

I am no longer a student dreaming of being an artist. I stopped going into Shakespeare and Company years ago. Walking past the shop was like walking past a building on a film set – a film that I was no longer appearing in.

But for millions of others it remained and remains a real place. Whitman's cantankerous nature preserved it for 60 years: a slice of Paris as it was … and many still want it to be.

That is a real achievement, a long life's worthy life work.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!