Warming seas and super-storms raze the cradle of aquatic life…

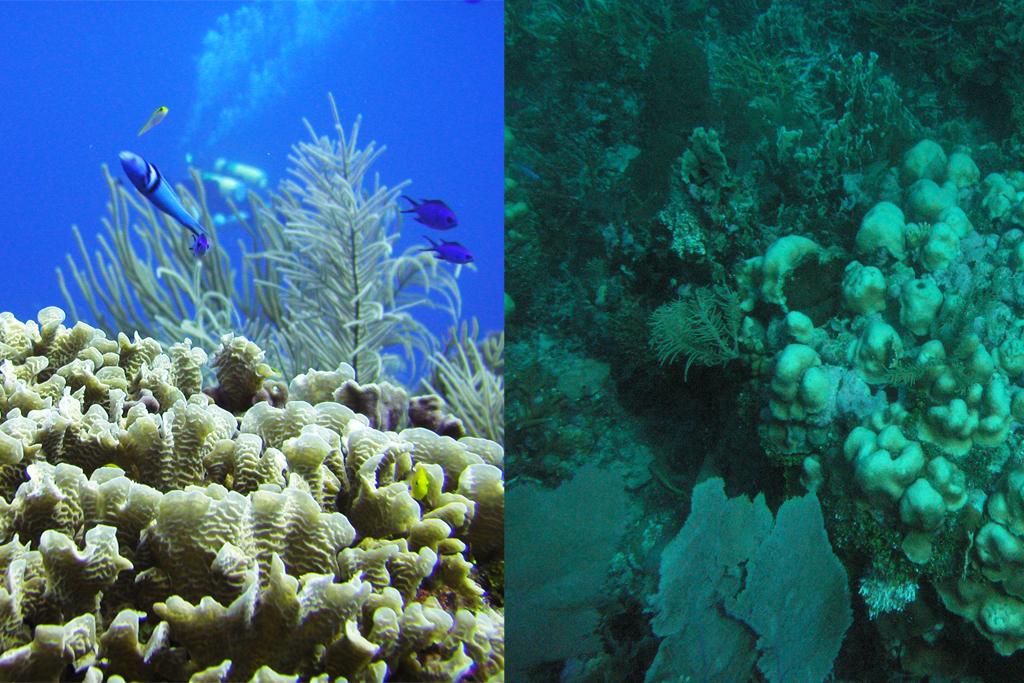

A healthy Aten Frills coral (left), and bleached coral (right). Climate change and super-storms are inflicting major damage on the world’s coral reefs, which are vital to aquatic life and ocean ecosystems.

CAYE CAULKER, Belize — Stripped of its color and smashed into pieces, the dead coral all but carpets the seafloor.

Here, just off Caye Caulker, a tiny, bucolic Caribbean isle that is a magnet for snorkelers and scuba divers, the ravages of climate change are clear to see.

Hurricanes have long been normal in this part of the world, and the spectacular reefs have adapted naturally to withstand the battering of storm waves.

But not like this.

Warming seas in recent decades have fuelled more frequent, stronger cyclones devastating the corals on an unprecedented scale and giving them less time to recover between tempests.

None have been stronger than Mitch, the 1998 mega-storm that killed thousands across Central America and, less obviously, also caused the submarine massacre which I am witnessing.

“The reef is going to be destroyed and it is not going to be very long now, maybe 20 years, if this keeps up,” says local diving guide Amado Watson, as we clamber back on his boat.

“Lobster used to crawl up the beach. You didn’t have to go and look for them,” he adds, noting how climate change is compounding the damage that inappropriate tourism and over-fishing are inflicting on the fragile coral. All this is having knock-on effects on the numerous marine species that call the reef home, relying on this complex ecosystem for nutrition, shelter and as a breeding ground.

For Belize, that could spell disaster.

Coral foundation

According to one study, the corals, combined with mangrove forests — a neighboring ecosystem that is mutually dependent on the reefs — contribute between $395 million and $559 million to this tiny nation’s annual $1.3 billion economy.

In other words, between 30 percent and 43 percent of the income of Belize’s 360,000 people comes from either tourism or fisheries rooted in the coral, or depends on the reefs as a barrier preventing storm surges from hitting land and disrupting other economic activities, such as agriculture.

“Belize would be in real trouble without the reefs,” says Nadia Bood, who heads the World Wildlife Fund’s reef program in Belize, and co-authored the report.

But the loss may be felt far beyond the Caribbean.

Nearly half of all pharmaceuticals currently available are derived from compounds found in plants and animals, and reefs represent one of nature’s last great frontiers for medical research.

Humans have barely begun testing corals for promising drugs, but potential cures for everything from cancers and asthma to heart disease and labor pains have already been discovered, according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

One drug derived from reefs and already widely used is Ara-C, extracted from a Caribbean sea-sponge and used in chemotherapy treatment for leukaemia and lymphoma.

Most visitors to Caye Caulker probably have no idea of the troubled state of its reef.

They typically spend idyllic days visiting healthy stretches of the Mesoamerican Reef, the largest in the Western Hemisphere, which runs down Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula, past Belize and along the coast of Honduras.

Highlights include diving with whale sharks or hammerheads and exploring the stunning labyrinths that glitter with a kaleidoscope of polyps in a bewildering array of shapes and sizes, and, of course, the tropical fish that call them home.

But Watson, 42, has taken me to a part of the reef that no tourist would want to see.

There are splashes of color here and there, from new corals growing amid the wreckage. Staghorn, seafan and tube sponge polyps sway gently in the currents.

There are also a few fish knocking around, albeit just a fraction of what one could expect on a healthy reef. As we snorkel, a 200 pound tarpon — itself a protected species — cruises by.

But mostly the reef here is a watery ghost-town, the colors replaced by a drab monochromatic gray, and the coral lying broken across the seafloor. The fish we do see appear to be quickly passing through rather than actually living here.

The storm damage is just the most visible impact of climate change.

Sea temperatures are also rising — imperceptibly for humans so far, but enough to seriously stress the reefs’ delicate organisms, especially when doldrums becalm the Caribbean in the summer and fall.

Meanwhile, the oceans are also slowly becoming more acidic. Their chemistry has changed as they absorb the same carbon dioxide that causes global warming and is emitted by the burning of fossil fuels and other human activities.

“It is a cocktail of impacts, including acidification, warmer water and the hurricanes,” says Victor Manuel Vidal Martínez, a reef expert at Mexico’s National Polytechnic Institute for Advanced Studies. “They all work together.”

But perhaps the worst impact is coral “bleaching” triggered by that combination of problems, especially the warmer waters.

Can humans help?

The bleaching occurs when the reefs, in a desperate effort to survive external stresses, expel the tiny algae that give them their characteristic colors.

So far, the Caribbean has witnessed three major bleaching episodes, in 1998, 2005 and 2010. Sometimes the reef, which has taken thousands of years to grow, recovers, albeit very slowly. But sometimes the bleaching leads to the death of large expanses of coral.

And as the seas continue to warm and acidify, the bleaching is expected to get worse and worse.

Nevertheless, there are attempts to reverse the damage, including a coral nursery, run by WWF and local partners, where robust coral species with a better chance of resisting climate change are being cultivated. So far, some 4,000 pieces of coral have been replanted in damaged parts of Belize’s reefs.

“We try to not to give up hope and that is why we are looking at promoting resilient species,” says Leandra Cho-Ricketts, a marine ecologist at the University of Belize’s Environmental Research Institute, who is also involved in the project. “We recognize that we may not be able to stop climate change but we can do other things to help prepare the reefs.”

Back on Caye Caulker, chatting with Watson after our snorkeling trip, we are joined by Mauricio Funes, 42. He used to be a fisherman but is now a taxi driver, ferrying around tourists in one of the handful of golf buggies that pass for traffic on the isle.

“Fishing on its own is not enough anymore,” Funes says. “I used to be able to catch lobster with my hands, but not now. The reef is not what it used to be, and there are too many fishermen all doing the same thing. It is too tough.”

Yet even as a taxi driver, Funes’ livelihood, like that of the rest of Caye Caulker’s residents, ultimately depends on the corals that ring this tiny island.

And despite the best efforts of conservationists, no one knows whether the reef will survive and adapt to the new climatic reality, or end up entirely like the shattered coral that Watson showed me.

This article was edited by David Case – @DCaseGP

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?