Two of 39 soldiers convicted of rape in historic DRC trial, all military officers acquitted of rape

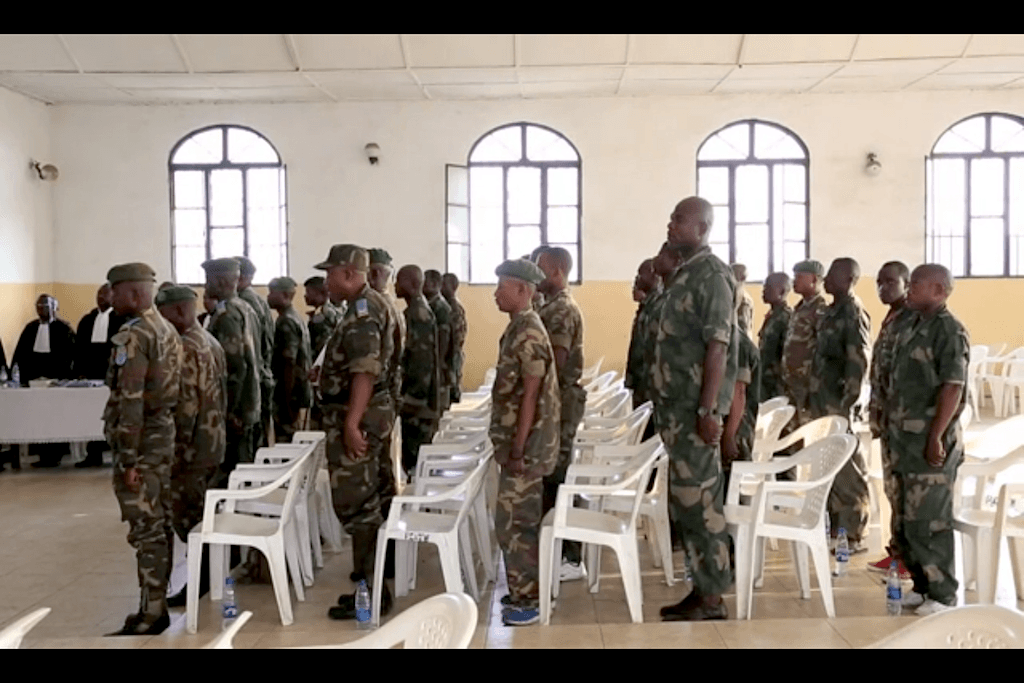

Just two of 39 Congolese soldiers — pictured here during their trial — were convicted of rape and sentenced to life in prison on Monday afternoon when a Goma courtroom handed down the verdict in the Minova trial, the largest rape tribunal in the history of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Editor’s note: This story is a follow-up to the first post, Seeking justice for victims of rape in Minova, in a new GlobalPost Special Report titled "Laws of Men: Legal systems that fail women." This year-long series looks at the breakdown in legal systems created to protect women’s rights around the world, and begins in the Congo at an unprecedented rape trial.

GOMA, Democratic Republic of Congo — Just two of 39 Congolese soldiers were convicted of rape and sentenced to life in prison on Monday afternoon when a Goma court handed down the verdict in the Minova trial, the largest rape tribunal in the history of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Thirteen soldiers were acquitted of all charges, while 24 were convicted of pillaging. Only 34 of the 39 defendants — all members of the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo (FARDC) — were present in the courtroom today, which also held about 250 spectators. The 56 victims who testified were not present for the reading of the verdict.

“Today is the big day for our justice,” said Colonel Freddy Mukenda, who read the judgment before the military court. “It is the day the we need to penalize the people who made these mistakes. The people who brought shame to our nation, to our government.”

The soldiers were on trial for mass rapes that occurred in November, 2012, when the FARDC retreated south to the town of Minova following a rebel takeover of the provincial capital of Goma — located in the eastern part of the country.

Upon arrival in Minova, the soldiers raped up to 1,000 women, according to official reports from the American Bar Association (ABA), who provided support to the proceedings. But only 56 women — those whose cases were “deemed most likely to result in a conviction” — testified during the trial. The women were reportedly selected according to the strength of their stories and their abilities to withstand tough questioning from the court.

More from GlobalPost: Seeking justice for victims of rape in Minova, DRC (VIDEO)

The unprecedented case of the 2012 Minova rapes is also considered an international war crime, by the standards of the International Criminal Court (ICC), due to the presence of continued armed conflict in the region, the scale of the attack and the profiles of the perpetrators.

According to Article 161 of the Congolese military code in the country's constitution, military courts have the exclusive jurisdiction to hear and determine cases on crimes against humanity in the form of rape.

But Article 215, also of the Congolese constitution, clearly states that international treaties and agreements, such as the ICC's Rome Statute — which is responsible for establishing the four core international crimes: crimes against humanity, genocide, war crimes and crime of aggression — supersede the country's penal code.

Under the Statute, mass rape is deemed a "crime against humanity" — which in the Statute is defined as "acts when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack."

Because DRC is a signatory to the Statute, officers with subordinates who were accused of rape or pillaging in the Minova trial could also be held legally accountable for their crimes by the ICC.

“The DRC is on the same team as the Statute of Rome,” explained Colonel Mukenda during the judgment. “And according to the Rome Statute, we must penalize those who pillaged or sexually violated the people, because it’s a war crime.”

Prior to today’s ruling, it was widely believed that 11 officers stood accused under the Rome Statute. But in handing down the verdict the court announced that there were, in fact, 13 officers on trial. Two of those officers, the court acknowledged, had never been present in court because they were fighting on the front line.

All told, 12 of the senior military officers who stood accused were acquitted for their crimes. One was convicted of robbing and pillaging.

Part of the difficulty with the case was a lack of hard evidence linking specific defendants to specific victims, according to advocates from the ABA.

Congolese soldier Sabra Chibanda had been identified by his alleged victim, who remembered his missing thumb, and was subsequently convicted of rape. Still, he vehemently defended his innocence following the announcement of the ruling.

“This justice is not right,” he said. “This justice is for people who have money. All these officers have money this is why they are free. But me, I don’t have money. So I’m going to prison.”

Soldiers who were convicted only of pillaging received reduced prison sentences of 10 years.

“I’m very happy for this justice,” said Nadine Saiba, a lawyer with the American Bar Association, who was part of the prosecuting team. “The people who I defended, they received justice.”

The victims of Minova were not present in the courtroom today, in part because the ABA feared the announcement would cause them emotional distress. Instead, the ABA said they plan to organize a day to travel to Minova to deliver the verdict to the women in a private setting.

In recent years, the DRC has worked actively to reform its national laws in an effort to address its long history of sexual violence.

Until 2006, there was no legal definition for what constituted rape under Congolese law. Instead, the definition was based on the 19th century Belgian penal code. In practice, this meant that predominately male judges would determine what constituted rape based on their own interpretation of the women’s’ experiences.

But in 2006, the country passed a law known in Swahili as vitendo vya haya, or “the law of shameful acts.”

The legislation, which guided the Minova trial, contains two clauses specifically concerning sexual violence.

The first clearly codifies the legal definition of rape, stating that it occurs in any incidence involving penetration, including the insertion of an object into a woman’s vagina, sexual mutilation, forced prostitution and forced marriage. It was also gender neutral.

The clause was significant because the standards of rape were defined in broader and harsher terms than that under the ICC’s Rome Statute.

The second clause addresses criminal proceedings and sentencing in crimes of sexual violence.

Though the 2006 law states that trials cannot last longer than three months, the Minova case, which began in late November 2013, carried on for five months.

The language in this legislation borrowed from international humanitarian law, which establishes the need to protect witnesses and provide psychological counseling for their well being, and also created mandatory minimum sentencing in rape convictions.

Combined, the two fragments of the law represent a unique approach to local justice in occurrences of international war crimes.

But even with these codes, the largest sexual violence case in the country’s history still failed to convict any senior officers of rape as a war crime in the Minova trial.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?