The Spanish are coming! Bad economy sends Spaniards packing for Latin America

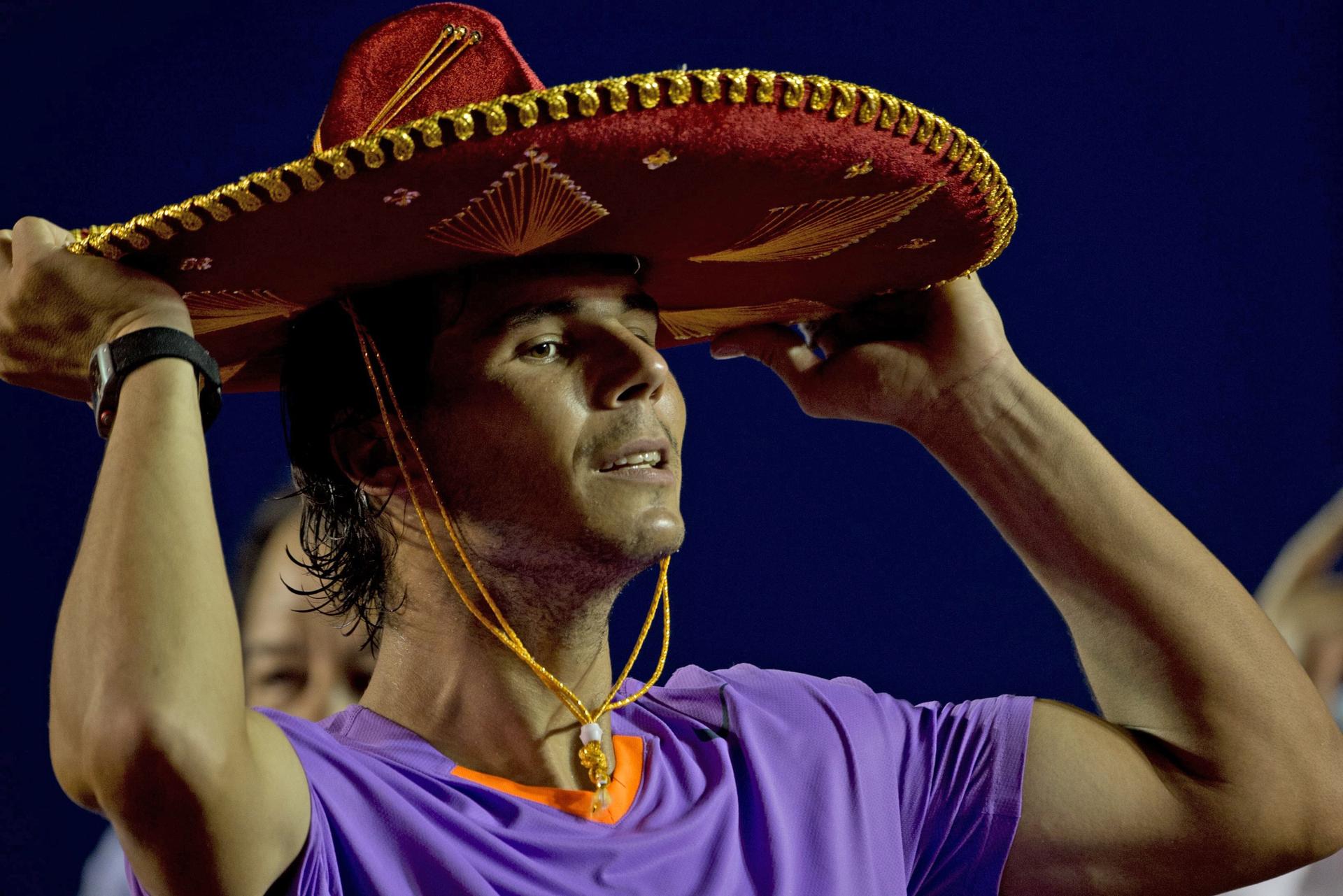

Rafael Nadal, the Spanish tennis star, puts on a traditional Mexican mariachi hat at the Mexico ATP Open in Acapulco, Guerrero state in March.

MEXICO CITY, Mexico — A Spaniard and a Mexican are drinking and chatting at a bar.

The Mexican, economist Rodrigo Alcazar, has recently returned here from graduate studies in Spain and is pondering the economic divergence between the two countries.

“How can I put this nicely?” he asks — then pauses dramatically, and smiles. “Spain’s economy is totally ‘chingada!’” he says, using a stinging Mexican expletive to drive the dire point home.

A waiter sets down a large glass of Indio beer.

The Spaniard, Javier Rodriguez, a marketer for Spanish telecommunications company Telefonica, knows his country’s fouled up situation — interminable recession and one of Europe’s highest unemployment rates — quite well.

Several years ago, Rodriguez left Spain to try his luck in the Americas. After working a string of jobs in Central America, he settled in Mexico last year. He might have returned home if he could, but failed to secure full-time work that would have enabled him to do so.

It turns out Rodriguez is not the only Spaniard fleeing hard times.

Spain’s economy had surged for much of the past few decades, luring Latin Americans in droves to brave migration overseas for a better life in what many of them consider “la Madre Patria.”

But now, with Spain in the doldrums, the Latin American influx there is waning, and many Spaniards are doing what Javier Rodriguez did: coming to the Americas, where economic indicators point admirably upward, not down.

“I know people from Spain who are going to come here to try to open a business because it is so hard to get financing [in Spain]. There’s a liquidity shortage,” Rodriguez says.

All this pondering and pilsner sipping is taking place at a popular, upscale cantina called La Cerveceria Nacional, which overlooks Mexico City’s Plaza de la Madrid, a park with a statue Spain’s government gave to Mexico in 1980. At that time, Spain’s nascent democracy was emerging from total isolation after a decades-long dictatorship, and the country sought to build commercial relations with its former colony.

Today, Spain wants even closer ties.

“We need more Ibero-America,” Spanish King Juan Carlos said in November at a summit in the Andalusian town of Cadiz, using the term describing the centuries-old links between the Iberian Peninsula and huge swath of lands in the Americas once called New Spain.

Many Spanish emigres and corporations from telecoms to energy, real estate and hospitality firms appear to have obliged him — they're seeking new opportunities in Latin America.

Chilean President Sebastian Piñera, in remarks at a January conference of European and Latin American leaders, summed up why: “The European Union is going through a very difficult time in terms of its economic crisis, stagnation, unemployment and fiscal deficits [while] Latin America is going through a very positive period, both compared to the rest of the world and to its own history.”

Indeed, more than two decades removed from its own debt crisis, Latin America now looks like an enticing option.

Its growth trajectory could still see hurdles placed by weaknesses in the euro zone and China. Still, the United Nations and the International Monetary Fund forecast Latin America's gross domestic product to expand 3.5 percent this year, up from 2.5 percent in 2012, and some of the region’s national economies could perform far better than that. The IMF said its growth estimate is "supported by a pickup in external demand, favorable financing conditions, and the impact of earlier policy easing in some countries."

By contrast, the Spanish government expects its economy to contract 1.3 percent this year, about the same rate it shrank last year.

Spanish multinationals expanding here is hardly novel, but some have been reaping new rewards.

More from GlobalPost: Euro crisis prompts Portuguese to return to former colony

In the 1990s, Spanish banks such as Santander and BBVA launched an unprecedented expansion effort in Latin America. Two decades later, some of the investment is paying off.

In 2011, both banks earned more in Latin America than they did in Spain. The same pattern unfolded in 2012. Despite writing off more than $7.7 billion in bad Spanish property loans, Santander, the euro zone’s largest bank according to market capitalization, posted profits of $2.6 billion that year, helped by strong returns on its operations on this side of the Atlantic.

In 2012, Santander raked in $19.1 billion in Latin America — almost double the $9.8 billion the company earned in its home market of continental Europe.

On March 21, BBVA’s executive chairman, Francisco Gonzalez, traveled to Mexico City to announce a plan to invest $3.5 billion in Mexico by 2016.

Mexico “has a solid and robust financial system that contrasts, without a doubt, with those [systems] in other parts of the world,” Gonzalez said at a press conference, speaking alongside Mexico's president.

Latin America also generates substantial revenues for Spain’s other early investors, such as energy firms Iberdrola and Endesa. In 2012, Endesa generated more hydroelectric power in Latin America than in Spain and Portugal put together. In 2009, Spanish energy giant Acciona built Latin America’s largest wind farm in Mexico. By the end of 2012 Acciona had more than doubled its wind output in Mexico.

Spanish hoteliers are already well established across the continent, and some are planning further expansion.

“We think there will be a very positive evolution in the Caribbean and in Latin America,” Gabriel Escarrer, the billionaire CEO of Mallorca-based Melia Hotels International, said at a January 2012 travel industry conference in Madrid.

As a result of all the movement and reversed economic trends, traditional migration patterns are reversing.

Overall, 310,000 fewer migrants went to Spain from Latin America during 2008-2010 in comparison with the previous three years. In 2011, the number of Latin Americans granted residency in Spain fell to half of the figure reported in 2007.

“Spain had a lot of people from Peru and Ecuador, but now with the crisis the Latinos who came to Spain for jobs are going back [home] … they don’t have work,” Rodriguez says.

Meanwhile, countries like Brazil, Chile, Mexico and others have become top destinations for job-hungry Spanish young professionals.

During the last three months of 2012, Mexico's immigration office issued work permits for 7,630 Spaniards.

A number of economic factors could be at play.

Although the 2008 global recession translated into an immediate contraction in Mexico, experts say the economic reforms the country had adopted over the previous two decades helped Mexico avoid a more serious collapse and also recover relatively quickly.

More GlobalPost analysis: Latin American equality — free markets or a left-wing success story?

Whereas corporate Mexico’s exposure to the 2008-09 global financial crisis was limited to isolated instances of debt problems, such as at cement maker Cemex and supermarket retailer Comercial Mexicana, Spain’s entire construction, banking and infrastructure industries have plunged into an ongoing state of calamity.

Now, as Spain’s economy delves deeper into double-dip recession, Mexico’s Finance Ministry predicts the country’s economy could grow by 4 percent in 2013, although the UN sees the figure slightly lower.

Mexico reports an unemployment rate of only 4.9 percent. In Spain, the jobless rate is 27 percent — its worst since the Franco dictatorship.

To be sure, the numbers tell a fraction of the story. Mexico still struggles with entrenched inequality. Pockets of Mexico’s south and low-income areas of the industrial north remain far more underdeveloped and impoverished than any part of Spain.

Many low-income residents in Mexico struggle with limited access to public services and formal sector jobs, analysts say. About a third of Mexico’s workforce ekes out a living in the “informal sector” — a designation that includes window washers, unregistered taco venders, shoe shiners, migrant workers, and domestic helpers.

Those services are in demand for white-collar Mexicans and foreigners like the Spaniards who come to work here — like the kind that come to La Cerverceria Nacional.

“In la Roma and Condesa, [the two upscale neighborhoods that surround La Cerveceria,] there are a ton of Spaniards,” says Rodriguez, the Telefonica employee, looking down at his massive mug of Indio beer.

He adds, “Mexico has more poverty and inequality, but it’s continuing to grow.”

More GlobalPost analysis: ¿Como se dice R&D? South America’s still learning how