Millennials learn to answer the dreaded question: ‘So… what do you do?’

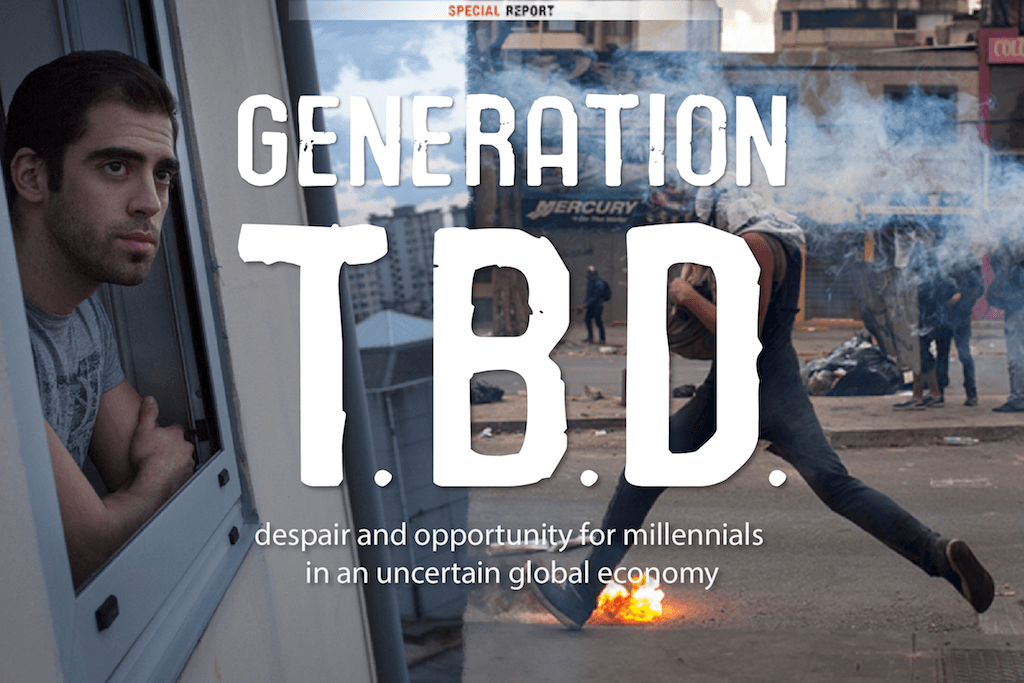

Editor's note: This story is part of a GroundTruth project we call "Generation TBD," a year-long effort that brings together media, technology, education and humanitarian partners for an authoritative, global exploration of the youth unemployment crisis. Tik Root is a 2014 GroundTruth fellow working on this project. He will be reporting on youth unemployment in Spain this spring.

MIDDLEBURY, Vermont — Everyone gets the question eventually. The asker may employ a slightly different tone, inflection or wording but will inevitably get to the point: “So… what do you do?”

For America’s young people – almost 6 million of whom are neither studying nor employed – the answer is often far from simple.

“It's a question that is expecting a really pithy answer of 'occupation — insert here,’” said Ava Kerr, a 2012 graduate of Middlebury College who is now living in New Orleans and has found enough part-time work — at both an afterschool program and a children’s museum — to barely make ends meet. “It's like Mad Libs. But the real explanation is much longer.”

Across the world, 12.6 percent of young people between the ages of 15 and 24 are unemployed; nearly triple the rate for those over 24. This is forcing youth everywhere to wrestle with the day-to-day challenges of being out of work. One of these difficulties, though less apparent than paying bills or getting food on the table, is handling the common questions about what they do and, implicitly, where they fit in society.

“Adults often define themselves in relation to their work,” said Dr. Stephen Hamilton, a professor of human ecology and the associate director of youth development at Cornell University. “If they either have no work at all, or they have work that is clearly not work that expresses who they are and offers them a chance to develop themselves and move higher, then they are likely suffer a loss of status and feel as though they're not really adults.”

Middlebury College recently hosted a conference that explored issues of youth unemployment around the globe. Joining the academics was a panel of recent Middlebury graduates, including Kerr, who are struggling to navigate the job market.

Like many of their peers, the panelists identified one of their near-daily challenges as how to answer the loaded “what do you do?” question.

Barrett Smith, 23, graduated from Middlebury in 2013 and took a position through Match Corps, which aims to train teachers for work in high-poverty charter schools around the Boston area. But Smith says conditions were far worse than he originally anticipated. His initial annual salary, he said, was $7,500 — well below federal poverty guidelines.

After two months of continued tensions with Match Corps management, Smith moved back to his parents’ home in Cincinnati and found seasonal work at a local UPS warehouse. After the holiday rush, even that came to an end.

In his hometown again, Smith is often met with the predictable questions, "Why are you back in Cincinnati? What are you up to?"

“My answer always comes with a laugh,” he said. “You laugh, and a lot of people will laugh with you because they're uncomfortable for you.”

Ashley Guzman, also an underemployed 2013 Middlebury graduate, routinely encounters the question in New York as well. After a temp job in accounting ended, she now works part-time as a hostess and occasionally babysits on the side.

“I always do the ‘Ahhh…’ and then answer,” she said, explaining her technique. “It prepares both me and that person for the fact that I'm going to say something that they're probably not going to be that impressed with.”

Smith, Guzman and Kerr are all part of a generation that Hamilton says is generally spending longer periods of time in a transitional stage, still at least partially dependent on their parents, when possible.

“[They are] no longer adolescents but not yet adults, because they haven't been able to take on these work roles that help to define them as people and give them the monetary resources to become independent,” said Hamilton.

With so many young people out of work around the globe, the phenomenon is by no means only an American one. There is no shortage of people who can relate to the youth unemployment crisis and the questions that it raises, including “what do you do?”

“I think the reason that it's funny or that there's this mutually shared humor is because [the problem] so pervasive,” said Kerr, as the other two nodded in agreement.

The panelists’ advice on handling the question runs the gamut from “tell it to them straight” to “deflection.” But they all agree that it is critical that their generation not lose its pride or start to doubt its worth.

“[Get] away from this place of guilt and self-imposed shame,” said Kerr, adding with increasing certainty, “It's not necessarily your fault. It's probably not your fault. I'm almost positive it's not your fault.”

More from GlobalPost: Generation T.B.D.: A dispatch from the streets of Caracas