Just how corrupt is Afghanistan?

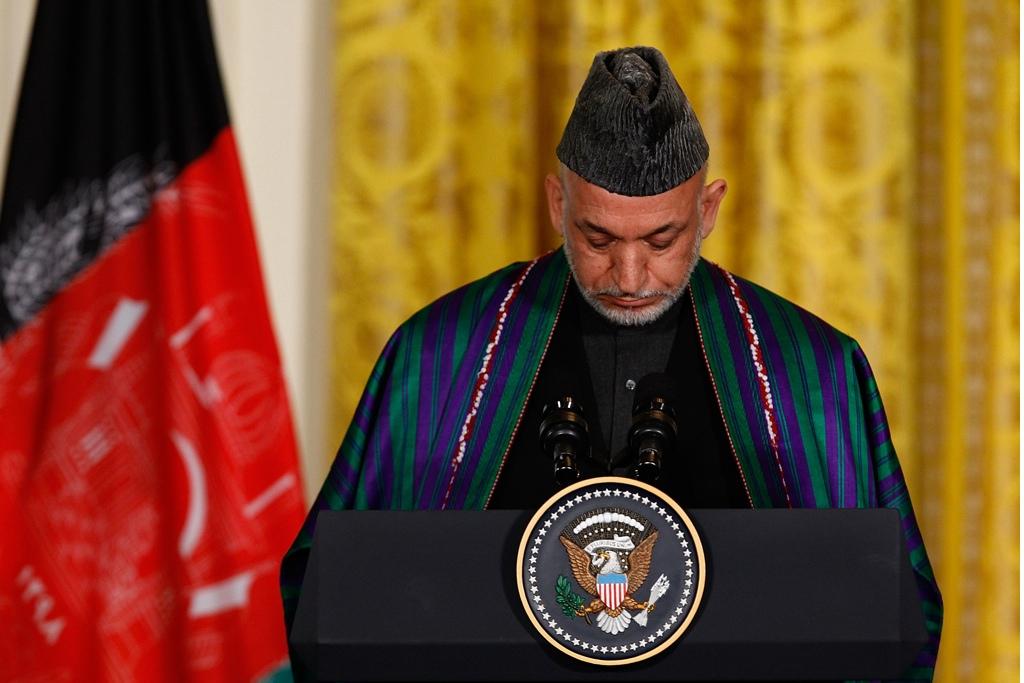

Afghan President Hamid Karzai.

It’s now official: Afghanistan ranks as one of the three most corrupt nations on Earth — splitting the crown with Somalia and North Korea, according to Transparency International’s 2013 Corruption Perceptions Index.

This is the second year in a row that the trio leads the list of the world's bad guys. In previous years, the best Afghanistan could muster was first runner up.

But just how pervasive is the problem? Can it really be true that after more than a decade under international stewardship, the most widespread skill the population has honed is graft?

More from GlobalPost: Turns out almost 70 percent of the world's nations are seriously corrupt

Let me start by saying that I loved every minute of my seven years in Afghanistan, and am fortunate to count many Afghans as close friends. I have happily put my life in their hands on more than one occasion, and would do so again.

But in many Afghans courage, nobility of spirit and graciousness toward guests exist side by side with rampant venality, fed, no doubt, by a lingering resentment of the foreign occupation.

A feeling that Afghans are owed some reparation for their pain doesn't help much, either.

I have spent significant time in several of Transparency International’s pantheon of the crooked: Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Belarus and Russia — all old haunts of mine — share the bottom third of the scale with Afghanistan.

None of them comes close to the casual disregard for what’s normally considered legality that I saw in my years in Kabul.

It starts at the very top.

One evening several years ago I was invited to a dinner at the US Embassy in Kabul. I was seated next to an Afghan-American official, and we were discussing corruption.

“How can we expect to make any progress when one of the most corrupt people in the country is the minister of counternarcotics?” I fumed.

Ahmed Zarar Moqbel, who had been interior minister until the graft and malfeasance in that organization proved too much for the international community to stomach, had recently been made drug czar. The British government, which had taken the lead on counternarcotics, cut off funding to the ministry upon his succession, apparently convinced that Moqbel himself was involved in drug smuggling.

Even in Afghanistan, he stands out.

The official looked at me, amused.

“Zarar is my relative,” he said.

I choked simultaneously on my food and my foot, and tried to stammer out an apology, but he just leaned toward me and laughed.

“Don’t worry, I agree with you,” he said. “I do not allow my family to see him.”

Moqbel has recently been named to head the Foreign Affairs Ministry.

In my experience, corruption in Afghanistan is everywhere, from the smallest office to the largest contractor. Examples range from the mildly irritating to the downright dangerous.

President Hamid Karzai insists the problem came with the foreigners. In an interview with author William Dalrymple, he shifted blame to his major benefactor.

“There is corruption, no doubt,” he said. “Our own petty corruption in the delivery of services was there before, is here today and will continue for some time. The big corruption was designed by the Americans. The contracts were used by the US government to buy influence in Afghanistan. It was designed to corrupt the Afghan political leadership so as to be usable by them.”

There may very well be some substance to Karzai’s accusations. After all, if the United States and its allies had not funneled nearly $700 billion dollars into Afghanistan over the past 12 years, it would not have been there to steal.

More GlobalPost analysis: Should we send more aid to Afghanistan?

Many in the international community also have a habit of looking the other way when it suits them.

Take the example of Karzai’s half-brother, Ahmed Wali Karzai, who was widely believed to have been a major figure in the drug trade before he was assassinated in 2011.

Ahmed Wali enjoyed good relations with the US — in fact, he was a paid CIA informant.

But the bulk of the responsibility has to lie with the Afghans, who have seized opportunities with alacrity.

In one office where I worked, the office manager was an expert at procurement. He had scoped out all the best suppliers in Kabul, and had a list of places to go. Very efficient, I thought, until I went to one of his favorite shops to buy a circuit breaker.

When I mentioned the name of my office, the store manager smiled understandingly.

“Ah, yes, this is what you want.” He fetched a raggedy-looking piece of equipment from in back. “It is reconditioned. Costs just a third of what a new one would. But don’t worry — we’ll give you a receipt for the full cost. We have an arrangement with your chief.”

A quick count of circuit breakers in the office ran to several dozen — the office manager was making $100 or so on each one. He also had a habit of hiring his relatives for minor jobs — guards, drivers. He would pay them a small fee and pocket the bulk of their pay.

Our resourceful manager was doubling or tripling his salary.

After I left, one of my former colleagues left behind sent me a message, typos and all:

“Im so sad of that situation witch is going on in our office in Kabul… corruption is in high level, making of corrupt invoices … hiring of relatives in office etc. … I want to send some documents to head office.”

But the head office was not interested. Exposing corruption is bad for business.

Our office was not a rich one; just imagine the scams the big boys must have thought up.

When I worked in Helmand, we liaised with a local official in Lashkar Gah, the capital. For the roughly two years of our stay we had to pay him a monthly “facilitation fee” not to make trouble for us.

While there, I lived in the governor’s guesthouse overlooking the river. It was lovely, except for the fact that the Taliban were across the water and occasionally fired automatic weapons in our direction. By the end of my sojourn the window was sandbagged to keep out stray bullets.

Helmand is a dodgy province: bombings, kidnappings, outright battles were common. Security seemed tight around the governor’s compound, except that one of our acquaintances, let’s call him Araf, would slip the guards a tab of hash to let him in without searching his car.

Araf, I should explain, was collaborating with the Taliban. He and his brothers used to make trips to the Iranian border to swap drugs for guns, which they would hand over to the insurgents. His father was arrested and incarcerated for his sons’ crimes, and Araf was desperately looking for money to buy him out of jail.

We stopped going to Helmand shortly after that, partly out of fear that our faithful “friend” would sell us to the Taliban to get the necessary funds.

Afghanistan is a world of fun-house mirrors.

One journalist I knew was insistent on bringing down a lawmaker from his home district, which bordered Tajikistan. The official, he claimed, was smuggling drugs.

An obliging governor from a poppy-growing province had made a helicopter available to get the parliamentarian home; since it was a government vehicle it was not searched. On every trip home the chopper was loaded with heroin or opium; the lawmaker’s brothers would then take the drugs and smuggle them across the border.

More GlobalPost analysis: The rise to a narco state

Ahmed (not his real name) brought me the helicopter pilot, who confirmed the story.

“But how do you know about the drug trafficking through Tajikistan?” I asked.

Ahmed laughed.

“Because my brothers are in business with them!” he said.

The story went untold, although it is common knowledge among many Afghans.

The ultimate in corruption was the presidential election of 2009.

Vote rigging was rampant, and far from subtle. Any election worker could produce sheaves of ballots all marked with the same distinctive squiggle — hastily filled out by the same hand.

According to one United Nations election monitor, there were at least 1,500 “ghost” polling stations — meaning that the hundreds of thousands of mostly Karzai votes they sent to Kabul were fraudulent.

The international community hailed the elections as a success, anointed Karzai as the legitimate winner, and, for good measure, fired the pesky official who tried to expose the fraud.

Afghan malfeasance reinforced by international complicity — come to think of it, maybe Karzai’s got a point.

Journalist Jean MacKenzie worked as a reporter in Afghanistan from October 2004 to December 2011.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?