Is it time to put a stop to bull running and bullfighting in Spain?

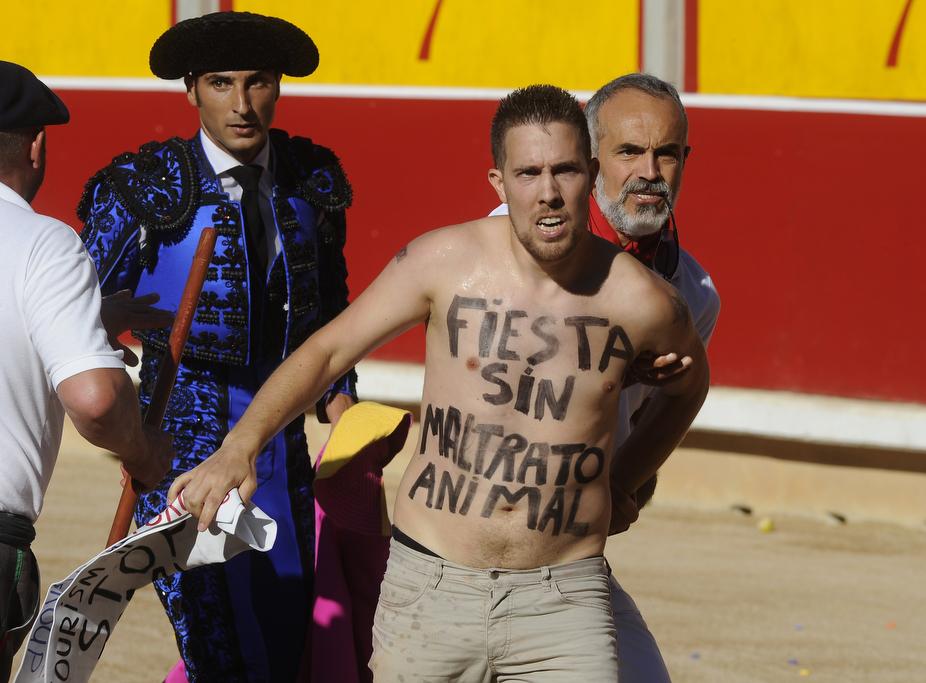

A man is detained after jumping into the bullring with the sentence 'Fiesta without animal abuse' written on his body during the seventh corrida of the San Fermin Festival in Pamplona, on July 13, 2015.

Seven people have been killed by bulls in festivals across Spain since July — including four over the past weekend — fueling the debate about whether spectacles involving the animals should be banned once and for all.

Most of the victims — including an 18-year-old man and an octogenarian pensioner — were killed during bull running events that are held every July and August in the streets of towns and villages throughout Spain.

Others, including matadors, have been injured inside and outside the bullring.

Bull running — where large crowds of people wearing white clothes and red kerchiefs around their necks dash madly through streets as they try to outrun a herd of bulls destined for bullfights — is a centuries-old tradition that began as a practical necessity.

More than 500 years ago the only way to transport bulls to the local bullfighting arena was to herd them through the streets. That is no longer the case and the tradition has evolved into an alcohol-soaked festival that attracts thousands of foreign tourists every year.

Bull running and bullfighting are hugely controversial in Spain and abroad. There are strong opinions for and against the spectacles.

The northeastern region of Catalonia, including the capital of Barcelona, and the Canary Islands have banned bullfighting, although critics claim Catalonia was motivated more by nationalistic reasons than animal welfare concerns. Running of the bulls is still allowed in parts of Catalonia, according to El Pais.

Numerous municipalities elsewhere in Spain are now considering similar bans or at least clamping down on public funding for bull running and bullfighting events that have been branded as cruel and barbaric by animal welfare groups.

PETA UK Director Mimi Bekhechi told The Independent the tradition was a “shameful, barbaric spectacle.”

“People who are gored during this display of human cruelty and idiocy have voluntarily chosen to participate, unlike the bulls, who have no choice in the matter and never make it out alive,” Bekhechi said.

Putting on bullfighting events is also expensive and often requires local governments to pitch in with financing — something many authorities can no longer afford to do following the global financial crisis. Newsweek, citing figures from the Interior Ministry, reported the number of bullfights fell 34.5 percent between 2007 and 2010.

But ardent supporters of bull running and bullfighting have been campaigning hard to preserve the traditions they say are an important part of the Spanish identity and the country's cultural heritage.

And they have some powerful people on their side.

Bullfighting returned to the coastal Basque city of San Sebastian last week, three years after it was banned. Among the spectators at the bullring was Spain’s former monarch, Juan Carlos. Carlos, known for his love of hunting animals, said bullfighting was a “Spanish asset that we have to support.”

And Spain’s right-wing government, led by pro-bullfighting Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, agrees.

In 2012, the ruling People’s Party forced the public broadcaster Television Espanola to resume live broadcasts of bullfights after taking control of its board.

The following year government-backed legislation was passed giving bullfighting special cultural heritage status in Spain.

Given the high-level support for bullfighting, the recent deaths are unlikely to end the sport.

But they will keep the debate alive, which is more than the bulls can hope for.