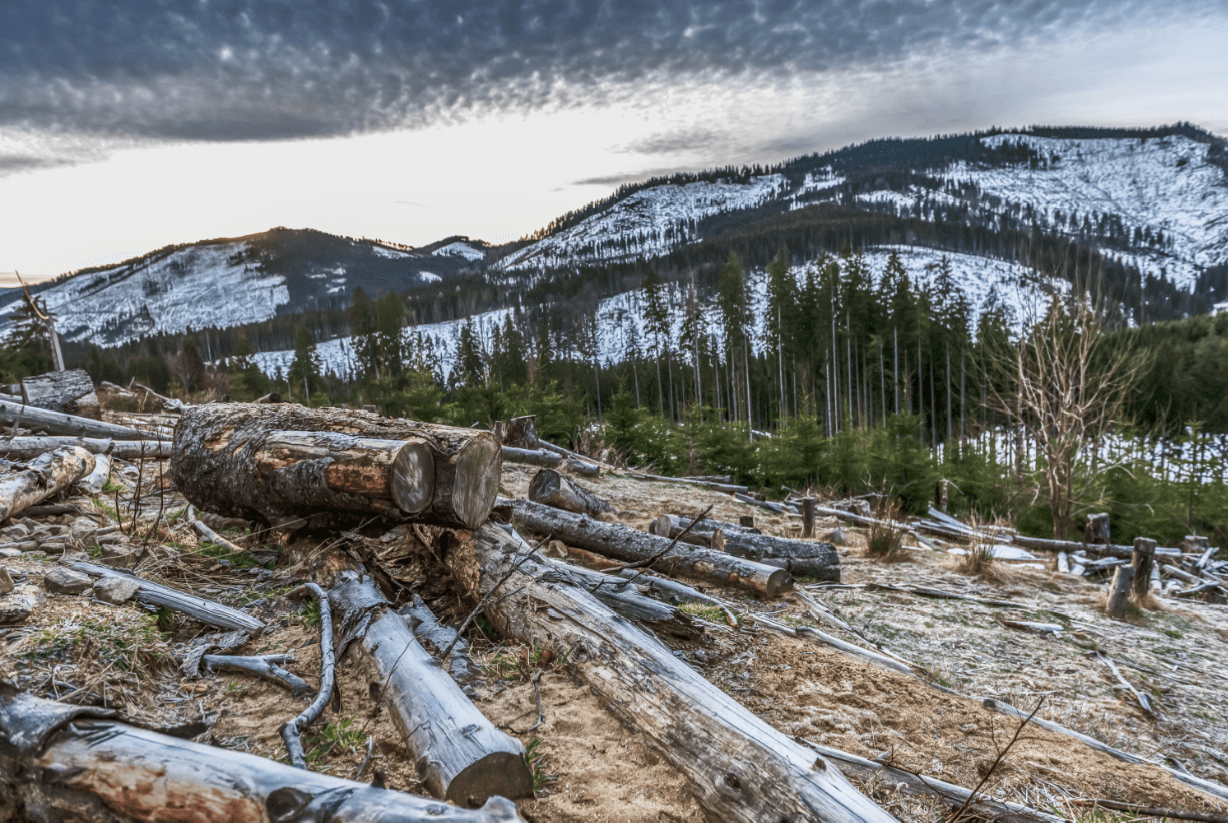

Illegal logging is destroying ancient forests in the Balkans

Devastated mountains in Romania’s Sebes Valley.

BUCHAREST, Romania — The old Russian Lada squeaks up the frozen forest road as dawn breaks in the Sebes Valley of central Romania’s Sureanu Mountains.

Fir trees whisper in the breeze and the smell of freshly cut wood lingers in the morning mist.

More than 3,000 feet above sea level, the first sign of disaster appears: an entire slope covered only in tree stumps.

Farther on, another graveyard of stumps comes into view, then another and another.

At the village of Curmaturi, a tourist haven of cozy wooden cottages, the scale of the devastation becomes unmistakable. Vast tracts of forest are being cleared here.

That’s because illegal logging is big business in Romania.

![]()

Officials check a peasant's wood transportation permit in Romania's Prahova county. (Magda Munteanu/BIRN/Courtesy)

Last year, the ITRSV, the Environment and Climate Change Ministry’s watchdog, discovered some 21 million cubic feet of illegally cut wood in the area. That’s the equivalent of 15,000 fully loaded trucks, which would fetch $45 million.

Romania isn’t alone. In other countries across the Balkans, big business, corrupt officials, lack of investment and institutional indifference are combining to deprive the region of the resource that provided its name — the Turkish word “Balkan” means “chain of wooded mountains.”

The illegal logging is threatening national parks, putting endangered species further at risk and allowing natural disasters to become more common.

Although much of the activity is driven by a lack of fuel, organized criminals are also moving into the business.

Back in Curmaturi, one villager evoked the lack of regulation here. “It’s the people’s forest,” he said, “they do whatever they want with it.”

Gheorghe Feneser, the prefect of the surrounding Alba county, says he’s declared war on what he calls the “wood mafia” as well as a local logging firm called Trans Monica he says is taking part in the illegal cutting.

He says he’s found evidence in the Sebes Valley and nearby Apuseni Mountains that more than 17.7 million cubic feet of timber were illegally cut during the last four years.

“Probably, 20 percent to 25 percent more wood is cut in Romania than is legally declared,” he says.

Last year, a small haul of unregistered wood cut by Trans Monica was discovered at Romania’s largest wood processor, the Austrian firm Holzindustrie Schweighofer.

Despite the discovery, the authorities have failed to pin any major illegal activity on Trans Monica or any other logging firm.

Courts dismissed two lawsuits against the firm, whose owner denies the accusations.

“I am not aware of any illegal cutting at Curmaturi,” Trans Monica’s owner Petru Cernat said. “If there was cutting there, I’m sure it was legal.”

Romania officially fells 678 million cubic feet of wood a year. Based on Feneser’s estimates, a further 120,000 truckloads of wood is illegally cut each year. That’s $350 million for Romania’s black-market logging business.

Figures collected for an investigation by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, or BIRN, show the problem is replicated across the region, where tracts of woodland the size of small countries are being leveled each year.

In Albania to the west, an area larger than the size of the capital Tirana was cut down in 2011, according to estimates.

In neighboring Macedonia, official figures for 2012 show a more modest loss from illegal logging, but one that’s increased threefold since 2008. According to estimates published by the Regional Environmental Center in 2010, the real figure for Macedonia is likely to be the equivalent of 5,000 trucks of wood a year.

Part of the problem lies in the lack of policing.

Romania’s ITRSV watchdog is severely understaffed. Rangers earning a paltry $270 per month are expected to monitor 1,235 acres each, with no cars, weapons, GPS systems or the right to arrest or even fine offenders.

Some 400 officers monitoring the activities of more than 5,000 companies lack specialist measuring equipment to verify whether paperwork allowing legal logging matches the amount of wood piled in yards or trucks.

In Albania, rangers prefer to turn a blind eye to the operations of violent illegal loggers.

Forest rangers who spoke on condition of anonymity said they were forced to patrol hundreds of acres and face violent organized criminals armed with only books of fines.

“I have kids at home and they want to have a father and they need food on the table,” one ranger said. “So sometimes we look the other way, not because we’re paid off but because our lives are threatened.”

![]()

A sawmill works at full speed in the Sebes Valley. (Magda Munteanu/BIRN/Courtesy)

Operating from Albania’s Lura national park, two rangers are charged with covering 24,700 acres.

The worst affected area is the remote Lake of Flowers, Liqeni i Luleve, where swathes of forest have disappeared.

Satellite images help show the scale of destruction during the past 20 years.

Official figures obtained by BIRN suggest that in 2011, up to 46 million cubic feet of trees were felled illegally in Albania — the equivalent of 11,600 acres, an area larger than the size of Tirana, the capital.

The estimates come from an official report compiled by Arsen Proko, then-director of forests in the Environment Ministry.

Facing up to the scale of the problem, the new environment minister, Lefter Koka, has ordered a ban on the export of charcoal and is considering a complete moratorium on logging for five years. Still, the felling of the forests continues.

In Macedonia, rangers have been drawn into shootouts with loggers.

Ljuboten, a village to the north of the capital Skopje, was the scene of some of the worst violence in Macedonia’s brief conflict of 2001 between ethnic Albanian fighters and Macedonian forces.

In October, violence returned to the mountain village when illegal loggers opened fire on the forestry police after they were asked to show their documents.

Although the situation in Ljuboten has since calmed, villagers say trucks loaded with wood still pass through every night.

Impunity is another problem.

In Romania, there have been no arrests for illegal logging, something activists believe wouldn’t be possible without official help.

In a bid to tackle the problem, the authorities have been working to change the forestry code, which governs how trees are logged, transported and traded.

A crucial area new regulations were set to address is the fraudulent use of transport permits, key to enabling the “laundering” of illegally cut wood.

Shell companies apply for transport permits to sell on for $30 each, BIRN learned.

Once an illegal logger secures a permit, his timber becomes legal and can be transported during the following 72 hours to its destination. If the police don’t stop him to note the transfer, the logger can reuse the same permit for more trips during that time.

However, the minister in charge of the reform, Lucia-Ana Varga, lost her job in a recent government reshuffle and the new code is now believed to have been shelved.

Jovan Mazganski, a Macedonian expert from the environmental association Eko-skop, believes the rise in illegal logging in his country can only have taken place with the authorities’ help.

“What’s worse is that within these groups involved in illegal woodcutting,” he says, “there are some people who are supposed to be defending the forest.”

“The officials either remain silent about this practice or are involved in it, showing that there’s large-scale corruption in forestry,” he adds.

Loose border controls are helping drive the cross-border business, experts say.

Nenad Kocik, president of the Macedonian environment group Vila Zora, says police operations do not go far enough.

“Dozens of hills are being totally deforested and we believe that officials should immediately change the law because the current punishments are too soft,” he says.

The chances of that are slim, however.

With huge profits to be made from the illegal exploitation of ancient forests, environmentalists fear half-measures, broken promises and inaction will do little to silence the chainsaws.

Magda Munteanu reported from Bucharest, Romania, Kristina Ozimec and Gabriela Delova, from Skopje, Macedonia and Alisa Mysliu from Tirana, Albania. The authors were awarded funding for the article as part of the BIRN Summer School of Investigative Reporting 2013.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!