Here are the signs that America’s longest war is finally ending

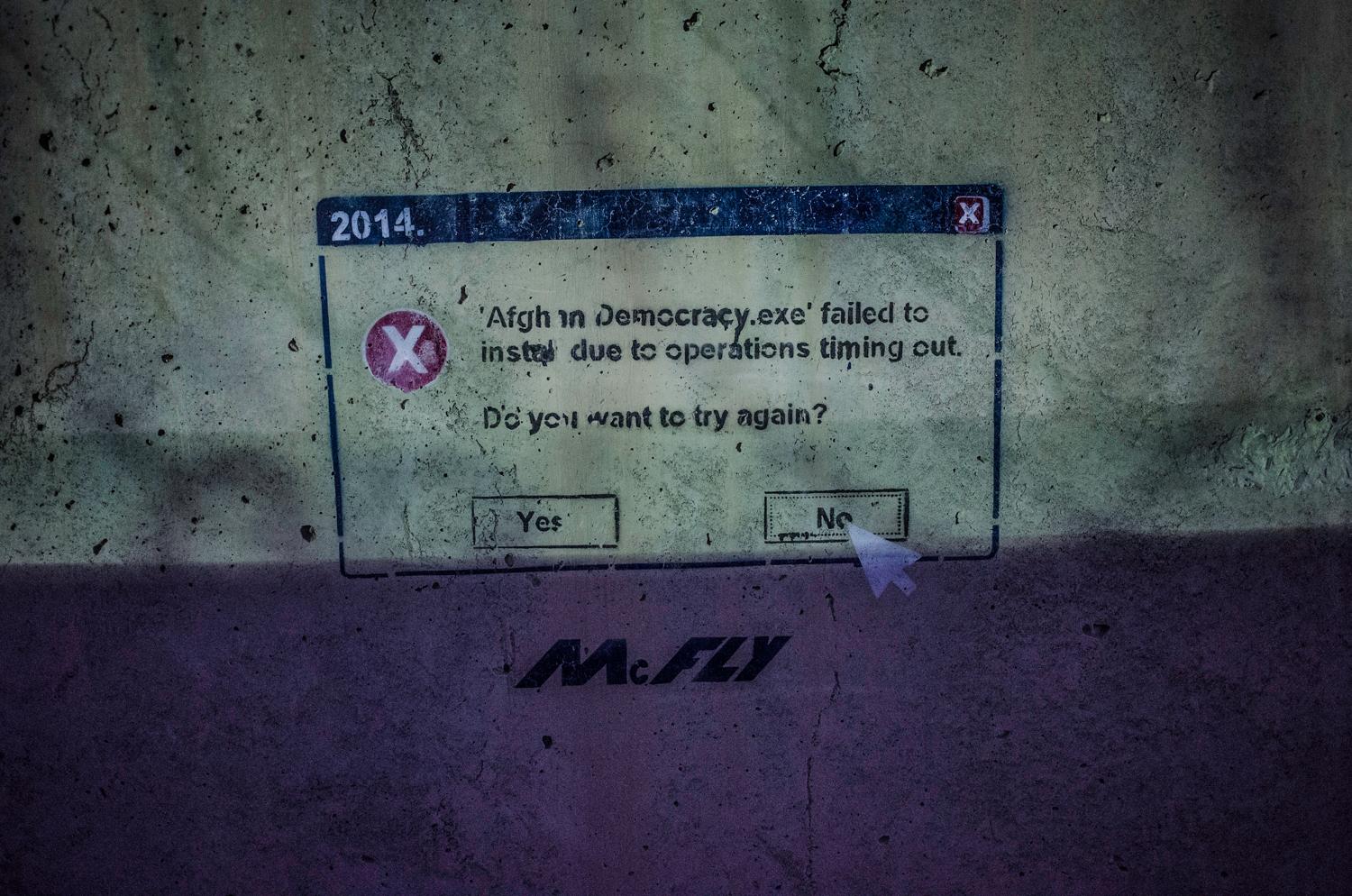

Stenciled on a blast wall at Kandahar Airfield, a soldier’s gallows humor echoes the uncertainty of Afghanistan’s future.

KANDAHAR, Afghanistan — Arriving here for the sixth time since 2010, I’ve never seen Kandahar Airfield as quiet as it is now. Most of the roaring diesel generators are gone, and the buildings they once powered are either abandoned or demolished. What was once a flood of traffic with huge armored convoys jockeying against trash trucks and fuel tankers on the airfield’s narrow streets has slowed to a trickle.

Every detail about this latest journey to Afghanistan speaks to the drawdown, the fading of America’s longest war into the dust of time that coats the landscape here. The signs of war are often subtle, but for someone whose entire adult life has revolved around the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, I pick up on them automatically.

For the first time in as long as I can remember, there were no uniformed soldiers milling about Boston’s Logan Airport, eyes heavy with anticipation, either of reuniting with family or heading back to the war. No news of Afghanistan on televisions or magazine covers — even if there was plenty of news about Iraq’s chaos.

I had planned to take a commercial flight from Dubai to Kabul and spend a day in the city before starting my coverage of the military drawdown. But I received word from another journalist that Afghan police, trying to cash in while they can, have been aggressively shaking down Westerners for bribes there. So rather than run that gauntlet for no good reason, I decided to fly with military contractors directly to the US side of Kandahar Airfield, known here as KAF.

![]()

(Ben Brody/GlobalPost)

These flights are rarely full, but this one was especially spare, carrying only about 50 passengers on a 162-seat jet. Most worked for DynCorp, a major contractor in Afghanistan. All three men I spoke with said they’d just spent their R&R vacation looking for work in the US, as positions in Afghanistan are becoming scarce.

One man, who declined to be identified because his employer had not authorized him to speak to the media, said he thought he’d have work in Afghanistan until April of next year. He had no idea what he was going to do next.

“I’ve kept my life pretty simple working (in Afghanistan and Iraq) and had no real life back in the states for about 10 years now,” he said. “My team here, the guys I work with are like my family.”

To underscore that point, he was transporting two huge boxes of Krispy Kreme donuts he’d bought in Dubai for his team. Yes, they sell Krispy Kreme in Dubai’s duty-free shopping area along with just about everything else you can think of. And this man, with his multiple tours as a contractor in Afghanistan and Iraq, is very much like many of the soldiers here who are on their fifth and sixth tours of duty.

He’s a lifer. He has only ever worked in the bewildering ecosystem of wartime army bases, as a soldier and then as a contractor, and he seems acutely aware of its toll on his life and how it is all coming to an end.

I’m the only journalist covering the military drawdown in Kandahar right now, but I expected that. I’m not here because it’s a huge, breaking story — it’s quiet and fraught. Everyone here is looking at the devastation in Iraq, thinking about what Afghanistan will be like in three years, and about what their time and tremendous struggle has meant.

![]()

(Ben Brody/GlobalPost)

Sgt. First Class Brock Jones, who is here on his fourth deployment, told me he spent a yearlong tour running a radio transmitter on Iraq’s Mount Sinjar, where the Yazidi people were trapped by ISIS militants. He said he has fond memories of the Yazidis and Kurds there, and it was painful to watch their plight on the news last week.

Of course, ISIS has no designs on Afghanistan and the Taliban are an entirely different beast, but Afghanistan is still in a precarious situation as NATO forces head home. The Afghan Army is a motivated fighting force, but badly hampered by an unreliable supply chain and an inability to maintain their equipment and vehicles. How can a country with no true national economy maintain a strong standing army on war footing?

Gains in education, particularly at girls’ schools, are at dire risk if the Taliban should return in strength. Today about 10 million children go to school in Afghanistan, 40 percent of them girls. Under the Taliban, almost no girls did.

There are about 30,000 US troops in Afghanistan right now, and that number will be reduced to just under 10,000 by the end of the year. While I’m here I’ll be looking at the ongoing drawdown, as well as getting a sense of the mission that will endure beyond the so-called “war’s end” — mentorship and advising of Afghan military and government leaders.

I’ll also visit one of the last remaining combat outposts in the country. These places are huge cultural touchstones within the military, and I want to see the process by which soldiers let them go, as they eventually must. Where there were once tens of thousands, now there are just a handful of US troops still living in austere conditions, still patrolling and fighting as though it were 2007, the war intensifying and stretching into infinity before them.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!