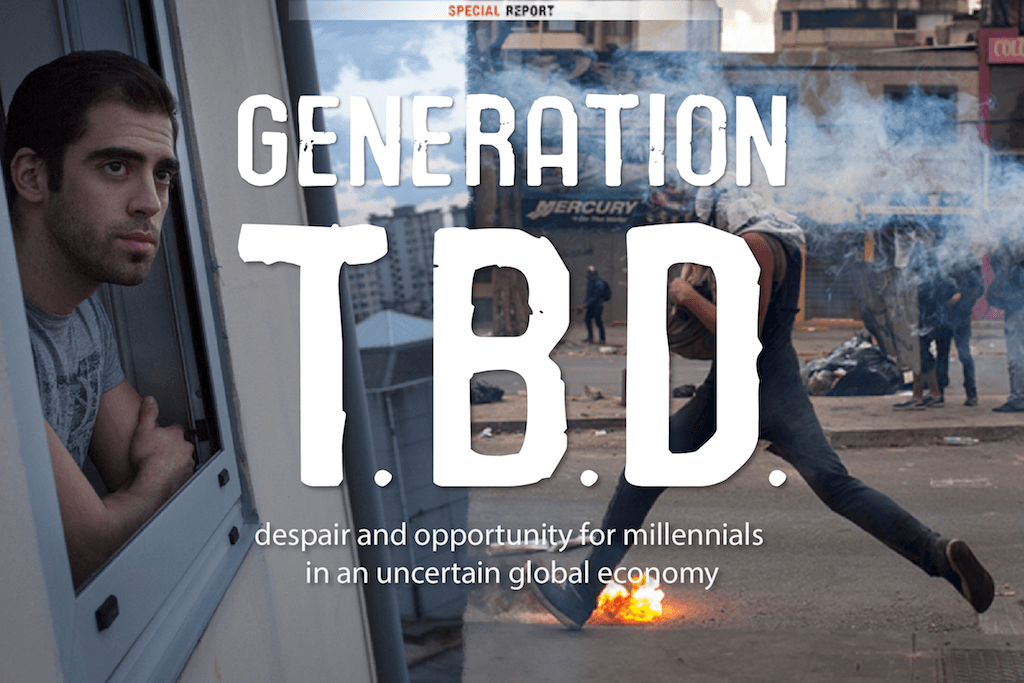

Generation TBD: An America full of Detroits

Editor's note: This story is part of a GroundTruth project we call "Generation TBD," a year-long effort that brings together media, technology, education and humanitarian partners for an authoritative, global exploration of the youth unemployment crisis. GroundTruth reporting fellows Eleanor Stanford and Saila Huusko, a Brit and a Finn, are traveling the American East.

BUFFALO, N.Y. and YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio — There was a joke during the aftermath of 9/11 that if al Qaeda had bombed Buffalo, the city would finally have gotten the national attention it needs.

As we drove into the city on US Route 33 one cold day last month, we soon understood the joke. In fact, it became clear that most of Buffalo’s traffic has been going in the opposite direction — and not coming back. We had heard that Buffalo lost 55 percent of its population during the twentieth century and that the city’s sprawl coupled with terrible infrastructure now makes it difficult for employed residents to get to work.

We saw many men trudging — it’s the only word for it — along road sides, bundled up against the snow and sleet. The roads were suddenly heavily potholed. It was snowing slightly and in the late afternoon the sky was the color of dishwater. A few young men in baggy clothes stared at the car as it passed. As two young women, we had been warned not to come down here.

But the streets didn’t feel threatening. What was striking was the absence of people on the sidewalks, of cars in driveways, of shops, of any sound, of American flags. This is Buffalo’s isolated residential east side. On nearby Philmore Avenue we passed four churches flanked by abandoned buildings, one with a sign reading “JESUS IS THE REASON FOR THIS SEASON,” partially buried by a snow drift.

A sign pinned to a post promised to buy houses for cash. And we wondered which houses would be for sale: the house at the top of the street with pretty blue awning, a rocking chair on the porch and St. Patrick’s Day decorations looped across the front? Or the building next door, with no door or windows but rooms full of furniture? Or the next building, also with gaping black holes where the windows should be and rotting wooden frame, but with a television playing in one of the upstairs rooms?

They were all small, colonial-style houses, standing alone on patches of grass that would be the envy of your average US city dweller were they located in a more prosperous location.

A month later we drove into Youngstown, OH and we knew what to expect. Youngstown, like Buffalo, sits by Lake Erie. Both cities were once centers of American industry and the plight of both has been overshadowed by Detroit: the biggest and statistically most shocking poster boy for America’s industrial decline. Residents of both cities told us with pride that the decay they lived with was just as bad as in Detroit.

“You don’t have to go to Detroit to get Detroit,” we were told by one Buffalo resident. The youth unemployment rate in Detroit is estimated at between 30 and 60 percent.

We soon came to realize that there is barely a residential street in either Buffalo or Youngstown that doesn’t have this jigsaw of family homes interspersed with abandoned buildings. In Youngstown we came across two houses side by side, each filled by a family’s possessions. Sofas were overturned, books lying spine-up on the floor, wallpaper peeling from the walls. A Winnie the Pooh teddy bear was propped up on a table, surveying the doorless entrance like a guard dog. An elderly neighbor told us the owners of both had “gone to California” a few years ago.

This decay nestled alongside the American ordinary was disconcerting to us, being two Europeans with a second-hand understanding of poverty in the United States. We kept asking ourselves, how has this happened? Who has been left behind? What would it be like to grow up here? These are the questions and crippling systemic disadvantages our coming reports will explore.

Our trips allowed us to see behind the numbers. In Buffalo, we had heard the factories had closed decades ago and that the well-paid jobs have never been replaced. On Main Street the vacant, seven-story Trico Plant’s sign looms over the downtown area. Trico invented the windshield wiper blade in 1917 and produced windshield wipers for decades at the plant before closing down altogether in 1998 after the company transferred operations to Texas and Mexico.

In Youngstown, we had heard high school graduation rates are among the worst in the country. We had heard that 4,000 houses have been torn down there since 2006. We met a young man who didn’t finish high school, but is employed by a grass-roots organization to tear these houses down and contribute to the direction of his neighborhood’s regeneration.

But we were in no way prepared for the eerie feel of a once-prosperous American city being slowly deserted by its residents — and ignored by the rest of the country. These towns are nearly devoid of many aspects of a developed country: employment, urban infrastructure and young people getting a comprehensive education. We are embarking on a journey into an America we never knew existed.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!