Crimea prepares for the world’s most predictable vote

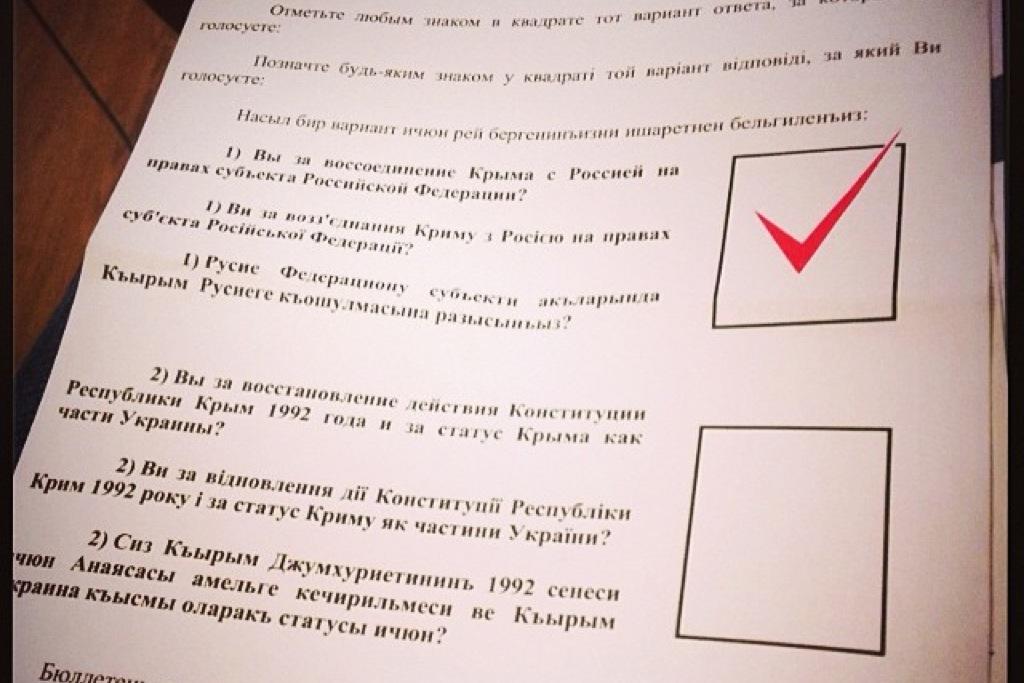

A mock-up of a Crimean referendum ballot handed out in Simferopol. Guess who gets the red check-mark?

SIMFEROPOL, Ukraine — Valery Kiselyov was just fired today. But the 35-year-old manager here in Crimea’s regional capital is holding his head high now that Russia’s coming to the rescue.

Gone will be the region’s high unemployment rate, crumbling infrastructure and substandard medical care, he says.

“Russia will pour all its available resources into developing Crimea so that it flourishes,” Kiselyov said enthusiastically on Friday, hoisting a placard outside the regional government building.

Although this Black Sea peninsula is still a day away from a referendum asking locals whether they want to join Russia, few here are expecting any surprises.

On Friday, the streets were abuzz with equal parts anger at the “fascist” authorities in Kyiv and praise for Russia’s overwhelming support.

Russian Cossacks and “self-defense” forces milled about the leafy center — past towering billboards declaring “Together with Russia!” — while the separatist government removed Ukraine’s national symbol from its headquarters, replacing it with a Russian tricolor flag donated by a delegation of politicians from Moscow.

With thousands of Russian troops already in control of the peninsula and the separatist authorities busy hashing out the logistics of annexation, the question around town isn’t whether, but when.

“We’re returning to our Russian homeland — it’s as simple as that,” said 77-year-old Yelena Alexeyevna.

Lenin, Cossacks. Simferopol.

The countdown to Sunday’s vote — when citizens will be asked to choose between a union with Moscow or de-facto independence — is ticking away amid fears of further destabilization in Ukraine.

On Thursday night, violent clashes broke out between rival protesters in the predominantly Russian-speaking city of Donetsk, where pro-Moscow sentiments remain high.

At least two people were reportedly killed and many others injured in a fight eyewitnesses alleged was provoked by the pro-Russian activists, long suspected by their critics to have been bussed there from across the Russian border.

Russia’s Foreign Ministry issued a statement Friday claiming that “armed right-wing radical groups” had in fact attacked peaceful demonstrators protesting against Kyiv’s post-revolutionary authorities.

Then came something darker: “Russia realizes responsibility for compatriots’ lives in Ukraine and reserves the right to protect these people.”

While Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov later denied Moscow plans to invade eastern Ukraine, where Donetsk is located, mass Russian military maneuvers along the border with Ukraine on Thursday have convinced the Ukrainian authorities otherwise.

Acting President Oleksandr Turchynov has warned that Ukraine should prepare for an invasion “at any moment,” while the country’s parliament on Thursday approved the formation of a 60,000-strong national-guard force.

But the relative calm here in Simferopol — save for the meandering, dour-faced toughs in mismatched uniforms — betrays the increasing tension between Kyiv and Moscow.

The mood downtown is almost festive, marked by small demonstrations in front of the government headquarters and on a nearby square where a statue of Vladimir Lenin still stands unmolested — unlike in many other Ukrainian cities.

Most enthusiastic here are the elderly, those born before the predominantly ethnic Russian region was given to Ukraine in 1954 by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev.

Pro-Russian bikers take a night ride in Crimea.

More from GlobalPost: Ukraine’s Jews tell Putin and his smear campaigns to keep out

Known for their political reliability — pensioners have long been the most active voters in post-Soviet Ukraine — they’ve also been the preferred targets for an aggressive Russian state media campaign that’s cast Kyiv’s revolutionary forces as anti-Russian bandits.

“Imagine my position: I was born in Soviet Russia, in Crimea, but they handed me off to Ukraine like a sack of potatoes, along with my native land,” said 65-year-old Aleksandr Naboichenko. “And now they’re prohibiting me from speaking in my native language.”

The separatist authorities have also appealed to local fears over Ukraine’s dismal economy.

In downtown Simferopol, slick posters compare the two countries’ pension wages, gas prices and healthcare opportunities — all more attractive, they claim, in Russia than in Ukraine.

Near the government headquarters, activists hand out leaflets addressed from the regional parliament listing “10 reasons to be together with Russia.”

Another official handout calls on Crimeans to head to the polls on Sunday to decide their fate, while declaring — in the very next line, in red ink — that “the fate and future of Crimea is inextricably tied to Russia.”

The closing statement is nothing short of Orwellian: “Dear Crimeans! We are confident your decision will be well thought-out and fair.”

Pensioners in Simferopol sing Russia's national anthem, with some help.

Critics have raised questions about the legitimacy of a referendum organized within two weeks and voted on in the presence of armed gunmen who had seized the regional government.

Originally scheduled for late May to coincide with Kyiv’s early presidential elections, it was later pushed back to March 30, then again to Sunday.

Earlier this week, Didier Burkhalter, chair of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), said the vote is “illegal” and in violation of Ukraine’s constitution.

Pro-Russian forces have repeatedly denied OSCE monitors entry into Crimea, once with warning shots.

Meanwhile, newly installed Prime Minister Sergei Aksyonov told journalists on Friday he expects a whopping 80 percent turnout for the referendum. He said he’ll accept whatever voters decide, but added that he’s convinced of the outcome.

“Currently, we believe — I personally believe — that Crimea should join Russia as a subject of the Russian Federation,” he said.

But not everyone’s enthusiastic.

Sergei, a 25-year old business manager, stood on a street corner Friday selling Crimean flags for $1 a piece. Asked about the potential outcome of Sunday’s referendum, he seemed largely detached: “I’m simply for Crimea.”

“Besides,” he added, “there’s no way back.”

A mock-up of a Crimean referendum ballot handed out in Simferopol. Guess who gets the red check-mark?

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?