Colombia just legalized euthanasia. Here’s why that’s a big deal

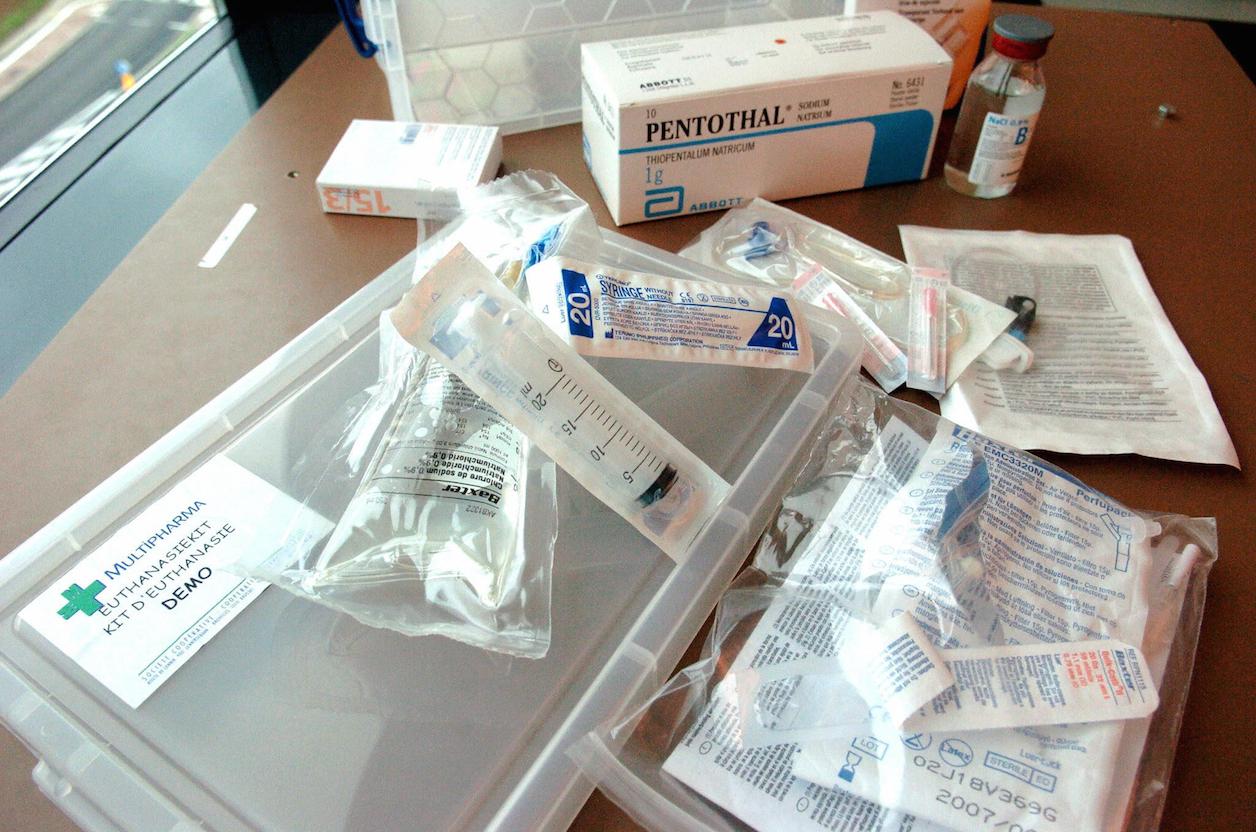

This is a euthanasia kit in Belgium, known for having the world's most liberal right-to-die law.

LIMA, Peru — Should a doctor be allowed to take a patient’s life? Colombia just said yes.

Terminally ill adults there can now ask a physician to end their lives for them, after the South American country’s Health Ministry last week made that right legally binding.

This is momentous — and highly controversial. It makes Colombia only the fourth nation in the world to allow euthanasia.

Euthanasia is different from medically assisted suicide, which is legal in many places. In assisted death, a doctor prescribes life-ending medication, typically pills, but the patient is the one who takes it. Euthanasia is when a third party actually administers the fatal dose, usually by injection. That raises all kinds of ethical questions.

There’s a growing global movement toward medically assisted suicide, like the high-profile case of Californian Brittany Maynard, a brain cancer patient who ended her life last November. But euthanasia remains a far more sensitive subject. The only countries that allow it, besides Colombia, are Belgium, Luxemburg and the Netherlands.

Colombia’s constitutional court actually ruled in favor of euthanasia back in 1997. But doctors were reluctant to implement the ruling because a separate law punished mercy killings with six months to three years in prison.

The Health Ministry’s new protocol finally puts the court ruling into practice, but with strict safeguards attached.

In the case of unconscious patients, relatives are required to prove patients previously expressed their desire to end their lives, in writing or by a video or audio recording.

And conscious patients have to first be informed of all their treatment options by the doctor. If the patient then insists on dying, the physician has to get authorization from a special panel made up of a doctor specializing in the patient’s condition, a lawyer, and either a psychiatrist or psychologist.

The Bogota-based Right to a Dignified Death Foundation (known by its Spanish initials, DMD) has been campaigning for this for three decades.

“This is a great step forward, not just for Colombia, but for Latin America,” said the group’s director, Carmenza Ochoa. “It’s a question of compassion. If an adult who is suffering and dying has requested euthanasia, why should others have the right to deny them?”

Yet euthanasia has many worrying that, deliberately or inadvertently, patients may be killed against their will.

Many religions — especially Catholicism, which holds a lot of sway in Latin America — vehemently oppose euthanasia and insist palliative care for terminally ill patients should be the only option on the table.

Others warn that euthanasia for terminally ill patients, who sometimes are unable to clearly express their opinions, could be the start of a slippery slope to societies looking to weed out people deemed undesirable.

And some doctors believe it violates their duty of care.

But Ochoa emphasizes: “If you kill someone against their will, that is not euthanasia, that is murder, and this law does not change that fundamental fact.”

Oregon-based euthanasia campaigner Derek Humphry adds that some doctors — sometimes with the family’s blessing, sometimes without — already hasten suffering patients’ deaths. There needs to be legal oversight.

“It goes on all the time, quietly, under the radar, all over the world,” says Humphry, who heads Oregon’s Euthanasia Research and Guidance Organization.

Oregon permits assisted death. That's why Brittany Maynard moved there after she was diagnosed with brain cancer at 29. She had just gotten married and was planning to become a mom, but was told she had just six months left to live.

Assisted suicide is also allowed in Montana, Vermont and Washington, while more than a dozen other states plus DC are considering legalizing it this year.

Germany, Switzerland and Europe’s Benelux countries also permit it, and Canada’s Supreme Court recently ruled in favor, too.

Because of the complex ethical differences between a patient committing the final act or someone else doing so, some vocal advocates of assisted suicide, like Portland’s Death with Dignity National Center, actually oppose euthanasia.

Roughly one-third of all patients with assisted suicide prescriptions never actually use their medication.

But experts say just having that option can make patients’ final days less stressful and even improve their quality of life as they near the end.

In Colombia, not everyone is pleased — particularly the Catholic Church, which opposes deliberately ending human life in any way.

In a letter to the Health Ministry, Colombia’s Episcopal Conference warned that the measure was a “serious attempt against the dignity of the sick and against the inviolability of the fundamental right to life.”

Ochoa, of Bogota’s DMD advocacy group, responds: “If others regard life as sacred, and are opposed to euthanasia, then we respect that. No one is going to push euthanasia on them. But for those who want euthanasia, their rights should also be respected.”

She adds, “It strikes me as such a terrible fate to become a living corpse, trapped in your body, suffering and unable to participate in the world.”

The rest of Latin America is unlikely to follow Colombia’s lead any time soon, notes Humphry, a former president of the World Federation of Right to Die Societies and author of the book "Final Exit."

“We tried to help set up similar organizations to DMD from Mexico to South America, and got nowhere. There just wasn’t the public will,” he says. “The reason for Colombia’s breakthrough owes an awful lot to DMD and the fact that they have been campaigning on these issues for some 30 years.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!