Britain’s Big Society is smaller than you may think

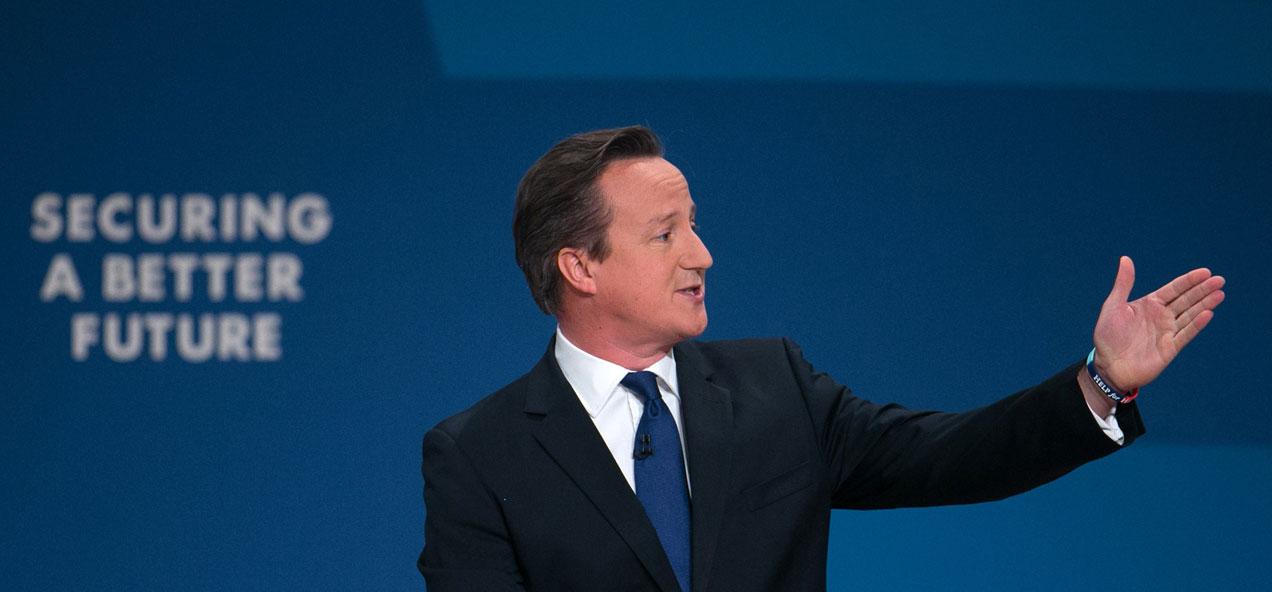

British Prime Minister David Cameron delivers his keynote speech on the final day of the annual Conservative Party Conference in Birmingham, central England, on Oct. 1, 2014.

DONCASTER, UK — Weeks after taking office in 2010, Prime Minister David Cameron warned that Britain’s dire finances were “even worse than we thought” thanks to the effects of the global financial crisis.

He called for serious belt-tightening to reduce the deficit and spending, measures he promised would be temporary.

Nevertheless, last year he admitted for the first time publicly that austerity is here to stay and that Britons should expect a permanently leaner state.

In place of the welfare system upon which many Brits had come to rely, he offered a vision for a “Big Society,” in which volunteer-led community programs would do for the needy what the state once did.

Since then, volunteers across the country have answered Cameron’s call to support those left floundering in Britain’s new social climate.

For all their hard work, however, in some places, the Big Society looks like little more than a thin line of defense against a crushing wave of poverty whose root causes aren’t being addressed even as the overall economy has started to boom again.

Among them, this South Yorkshire town north of London saw unemployment at 7.3 percent in July, the second highest rate in the country.

St. James Church stands at the end of a cigarette butt-strewn street lined with shuttered pubs and pawnshops. The church has been without a vicar since last year. Apparently God doesn’t call anyone to Doncaster, parishioners say sardonically.

In its best days, Doncaster was home to thriving coal-mining and train-building industries. A railroad tycoon built St. James in 1858 to serve his workers’ spiritual needs.

The last train carriage was built in 1962. The coal pits closed in the 1970s and 1980s. Like many northern industrial towns, Doncaster fell into a depression from which it has never fully recovered.

When new businesses or services do come to the area, Doncaster frequently loses out to Sheffield, a bigger city 20 miles away with a thriving student population and better transportation links.

“It is pretty much at the bottom of the heap for where you’d want to live,” says Glenys Gosden, a speech and language therapist who runs a food bank on her day off.

The food bank opened in March 2013, a month before the benefit reforms began. For two hours each Friday, volunteers hand plastic bags stuffed with canned food, dry goods and a few hardy vegetables to anyone who walks through the door, no questions asked.

The parcels are subsidized, not free. St. James asks for a contribution of $4 for around $12 to $16 worth of food, although Gosden says those who can’t pay haven’t been turned away.

“I wouldn’t come here personally but I’ve got two kids,” said Daniel Holland, 25, a Royal Navy veteran who traveled an hour on the bus from his home for two bags of food.

He lost his warehouse job three months ago when the company was liquidated and its employees were laid off.

Holland’s savings from his military days held them over for a month, he said, and unemployment benefits stretch only so far. When there was no longer enough money in the budget for three solid meals for the children, ages 6 and 4, he pushed nerves and pride aside to visit St. James, the closest food bank to their home.

He was grateful the food is packed in recycled grocery store bags: “The kids just think we’ve been shopping.”

Holland was optimistic he’ll find work soon, and grateful to the St. James volunteers who offered tea and sympathy. When talk came to politics and Britain’s upcoming general election in May, however, his sunny outlook ended.

“There’s nobody to vote for,” he said. “Labour should be on our side, but they’re all corrupted by the Tories. It’s permanent austerity, forever. Because of that, a lot of people are losing hope. It’s the bleak future until something changes.”

Change may not be coming any time soon.

Speaking at the Conservative Party’s annual convention last week, Cameron promised $11.6 billion in tax cuts for Britain’s middle-class families. That bumped the Tories ahead of Labour in the polls for the first time in three years.

“We believe in aspiration and helping people get on in life,” Cameron told the crowd in Manchester.

He didn’t mention how he plans to pay for those tax cuts, and the applauding crowd didn’t seem too bothered.

The answer may have been revealed a few days earlier during a less-heralded speech by Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne, the UK’s finance minister. He pledged to continue benefit and public spending cuts despite the fact that there isn’t enough well-paying work in many parts of Britain to keep people afloat.

At 6.4 percent, UK unemployment is at its lowest level in six years. But the decrease is largely the result of sluggish wage growth, which has made it cheaper for employers to hire workers but harder for employees to earn a decent living.

Wages fell 0.2 percent in the quarter ending in June.

"We're still feeling some of the negative effects of the recession and that can be seen by the lack of real growth in real earnings," says Jim Hillage, director of research at the Brighton-based Institute for Employment Studies.

"People feel they need a job, and when they get a job they work very hard,” he adds. “But they're not feeling the benefits. People are still struggling."

Food bank use has nearly tripled during the last year, according to the Trussell Trust, the country’s largest food bank provider. More than 900,000 people received a three-day parcel of emergency food from the charity in the last year.

Half the recipients said they needed the food as a result of sanctions on their benefits or because of chronically low income.

Food bank providers around Britain said their clients tend to be people who have found themselves in dire straits as a result of exceptional circumstances like job loss or a sudden change to their benefits.

More from GlobalPost: Threats to the post-war order are fueling a European malaise

Liz Townson’s Baptist church in the east England county of Norfolk is one of three supporting the Great Yarmouth Food Bank, where visitors quadrupled in the five months between February and July.

“They’re people who have had a problem,” Townson, a retired teacher, said of typical recipients. “You sit them down and they end up crying. People come in and say, ‘I’m contemplating suicide.’ I’ve had people say that to me three times in a week. I feel like I need a chaplain in there.”

Nearly 400 miles north in Leith, Scotland, the Rev. Iain May of the South Leith Parish Church is also at a loss. His church’s food bank has served more than 2,000 people in the last ten months.

“Why in the 21st century have we gone through 15 tons of food? Why do they not see that?” he says of the ruling classes. “This is not a political game. It’s a big deal. This is people’s lives.”

The article you just read is free because dedicated readers and listeners like you chose to support our nonprofit newsroom. Our team works tirelessly to ensure you hear the latest in international, human-centered reporting every weekday. But our work would not be possible without you. We need your help.

Make a gift today to help us reach our $25,000 goal and keep The World going strong. Every gift will get us one step closer.