Afghanistan: Should we stay or should we go?

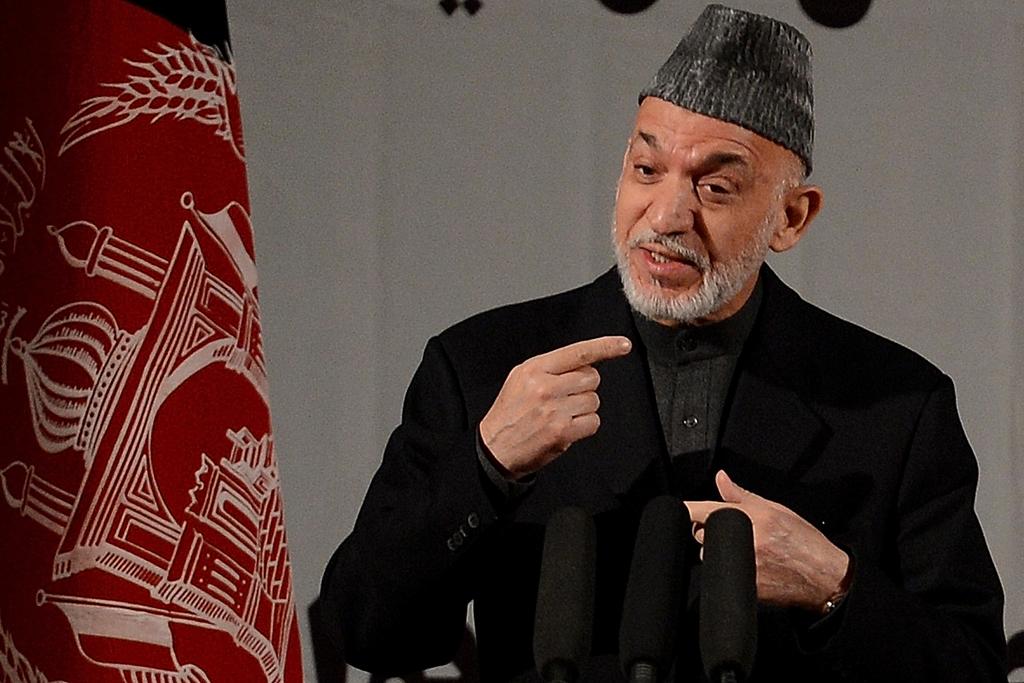

Afghan President Hamid Karzai speaks at a gathering of women to mark International Women’s Day, in Kabul on March 10, 2013. Karzai’s recent comments about US-Taliban relations have certainly raised some eyebrows, but it’s clear as the US combat mission enters its final stages that the situation is far from rosy.

BUZZARDS BAY, Mass. — Afghan President Hamid Karzai certainly knows how to ruin a party. As newly anointed US Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel made his maiden voyage to Kabul last week, Afghanistan's president all but accused the United States of being in cahoots with the Taliban.

At a televised press conference in Kabul on Sunday, Karzai condemned Saturday's suicide bombings in Kabul and Khost that killed at least 19 people. The Taliban claimed “credit” for the attacks, saying it had wanted to send a message to the defense secretary.

But Karzai was not content with diplomatic niceties. Instead he lashed out at his US allies, saying they and the Taliban were jointly trying to paint a black picture of what would happen in Afghanistan once the US forces withdraw.

The US combat mission in Afghanistan is winding down, with the last troops scheduled to leave by the end of 2014.

“Yesterday’s bombings in Kabul and Khost didn’t aim to show Taliban’s strength — indeed, they served America,” said Karzai. “By those bombings they served the 2014 negative slogan … These bombings aimed to prolong the presence of the American forces in Afghanistan.”

The Afghan president also accused the US of holding secret talks with the Taliban behind his back, something both Washington and the Taliban have repeatedly denied.

US Marine General Joseph Dunford, who heads the coalition forces in Afghanistan, called Karzai's charges "categorically false."

"We have fought too hard over the past 12 years, we have shed too much blood over the last 12 years, we have done too much to help the Afghan security forces grow over the last 12 years to ever think that violence or instability would ever be to our advantage," he said, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Hagel himself was a bit more muted, while giving no ground on Karzai’s somewhat bizarre accusations.

"I was once a politician,” said the former Nebraska senator, “so I can understand the kind of pressures that especially leaders of countries are always under, so I would hope that, again, we can move forward — and I have confidence that we will."

Karzai’s latest tantrum could be a reaction to the US cancellation of a promised handover of Bagram Prison that was supposed to take place on Saturday.

He had been demanding full control of detention centers in Afghanistan for years. During his summit in Washington with President Barack Obama in January, he touted the handover agreement as one of his proudest accomplishments:

“Concerning Afghan sovereignty, we agreed on the complete return of detention centers and detainees to Afghan sovereignty, and that this will be implemented soon after my return to Afghanistan,” said Karzai in a televised press conference. “We also discussed all aspects of transition to Afghan governance and security.”

But problems have persisted ahead of the handover. The US is expected to make sure Karzai does not release detainees Washington deems to be a continuing danger; Karzai is expected to try to avoid interference from his major ally in what he describes as an important issue of Afghan sovereignty.

Last week, he told a joint session of the Afghan parliament that as soon as he had full control of the prison, he would begin to release detainees.

“We know many innocent people are being held there. We would free them, despite criticism,” he said.

Karzai refused to agree to the Americans’ demands that they be allowed a virtual veto over the release of prisoners. The White House has been fighting with Congress over the handover, and did not want Karzai’s words to spark another round of correspondence similar to the one between Obama and Howard “Buck” McKeon, R-Calif., chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, in February.

“I am particularly concerned about the disposition of detainees who continue to represent an enduring and continuous threat both to our US forces on the ground in Afghanistan as well as to US national security,” McKeon wrote. He emphasized it would be “completely unacceptable” for the US to fail to maintain custody of such prisoners.

The US government insists these are just “minor hiccups” in the agreement over the prisoner handover, but Karzai’s intemperate outburst on Sunday might throw a spanner in the works.

All of this has cast a long shadow over Hagel’s visit, and is expected to further complicate discussions over the size and shape of any residual US force to be left in Afghanistan after 2014.

In January, White House officials indicated it was considering a “zero option” but military sources reportedly have advised keeping a significant number of troops in country.

GlobalPost analysis: Karzai goes to Washington

Gen. James Mattis, of the US Central Command, told the Senate Armed Services Committee last week he envisioned an overall force of 20,000 in Afghanistan post-2014, of which more than half — 13,600 — would come from the US.

This is not the first time the notoriously volatile Karzai has gone off the rails.

In years past, he has alternately threatened to declare war on NATO, vowed to join the Taliban, and blamed the US for the corruption that permeates his administration.

Whenever challenged, the Afghan president’s first reaction seems to be to point the finger right back at his accusers.

In February, Karzai ordered US Special Forces to leave Maidan Wardak, a province that serves as the gateway to Kabul, amid accusations that Afghan forces trained by the US, and perhaps American forces themselves, had been involved in torture and abuse of Afghans.

This came after a United Nations report documenting widespread torture and abuse within Afghan prisons by Afghan authorities.

Karzai may have reason to feel a bit insecure in his relationship with the US at the moment. He does not enjoy the same warm and indulgent connection with the Obama administration as he seemed to have with the team around George W. Bush, which virtually installed him as the leader of Afghanistan in 2001.

In a now famous dinner in Kabul in February 2008, three US senators tried to persuade Karzai to tackle corruption within his government. The Afghan president denied corruption was a serious problem, prompting the head of the delegation to throw down his napkin, say “this dinner is over,” and stride from the room, accompanied by his colleagues.

The napkin thrower is now the vice president, Joe Biden; his companions on the trip were Massachsuetts Sen. John Kerry, now secretary of state, and Nebraska Sen. Chuck Hagel, now defense secretary.

Karzai’s push-pull tactics are likely to inflame an already divisive debate within the US about the continued American presence in Afghanistan.

After 12 years of blood and sacrifice, in which more than 2,000 US soldiers have died and hundreds of billions of dollars have been spent with little clear effect, the American people are tired of the war. President Barack Obama has staked much of his reputation on bringing the troops home and extricating the US from the seemingly endless conflict.

Karzai’s accusations that the US is intent on prolonging its presence in Afghanistan appear wildly at odds with what some see as a mad rush for the door.

And while the Afghan president may complain about getting the US troops out of his country, many Afghans worry about what will happen once the foreign forces leave. Officials in both countries pay much lip service to the battle readiness of Afghan security forces, but even the Pentagon reportedly has doubts the Afghans will be able to step into the breach when the foreign troops clear out.

On Monday, a fresh insider attack by an individual in an Afghan army uniform in the Wardak province killed two US troops and a number of Afghans.

Still, in addition to security concerns, there is fear of economic collapse. Much of Afghanistan’s economy relies on international aid, and investors are wary of the post-withdrawal environment.

For now, all sides seem intent on smoothing things over and trying to move forward. But a very long and perilous road stretches between now and the end of 2014.

GlobalPost in-depth: The Handover

Jean MacKenzie worked as a reporter in Afghanistan from October 2004 to December 2011, first as the head of the Institute for War and Peace Reporting, then as a senior corespondent for GlobalPost.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!