Little Uruguay beat Big Tobacco in court, keeping the right to large, grotesque cigarette warnings

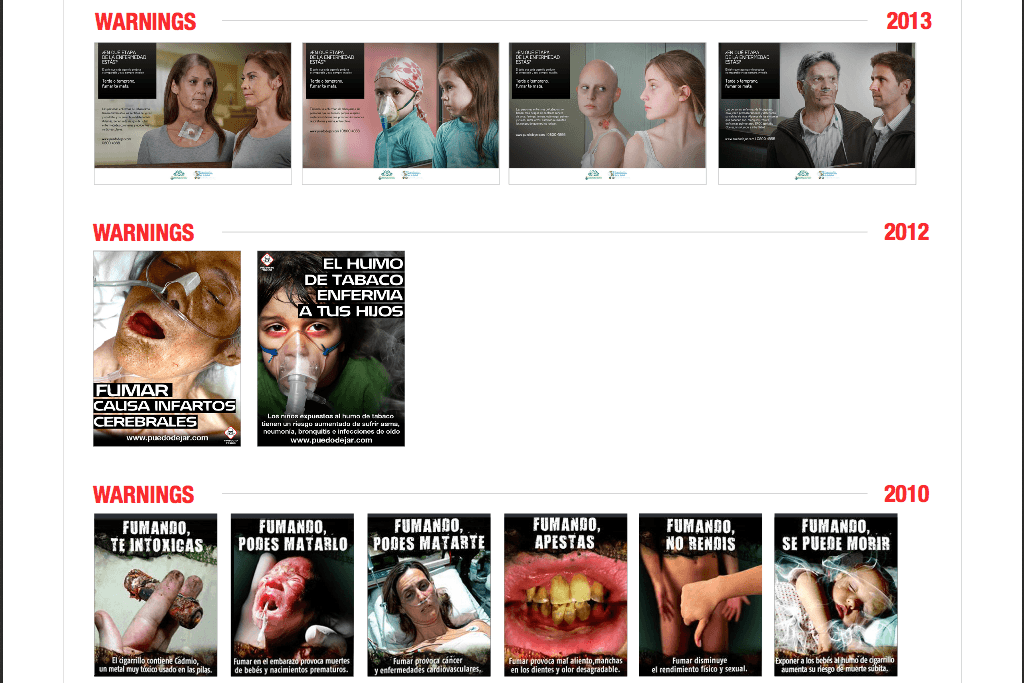

Uruguay's smoking warning labels, via tobaccofreekids.org and the Tobacco Labelling Resource Centre at Canada's University of Waterloo.

Your cigarettes could one day look a lot grosser, with the packaging depicting rotten teeth, charred lungs or cancer-ridden skin.

It’s all thanks to a judgment in a landmark case between the tiny South American country of Uruguay and the giant tobacco company Philip Morris International. The ruling has sent a stark message to the globe’s cigarette behemoths: Don’t try to mess with a government’s good-faith efforts to protect consumers from your harmful product.

The World Bank tribunal struck down the tobacco company’s lawsuit against Uruguay last week, but supporters of the country in the case say the judgment will have impacts far beyond its borders.

“Philip Morris basically tried to intimidate and bully Uruguay,” said Matt Myers, president of the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, a Washington-based advocacy group. “This decision is going to reverberate around the world, for a lot of reasons.”

The company says it has accepted the decision.

In 2010, Philip Morris had filed a lawsuit against Uruguay, claiming its anti-smoking policies violated a treaty between Uruguay and Switzerland, where the company is based.

There were two key Uruguayan measures prompting that suit: The country required that at least 80 percent of all cigarette packaging carry images warning about the health risks of smoking; and tobacco companies were barred from selling different versions of the same brand of cigarettes (think: Marlboro Reds versus Marlboro Lights).

Myers said that many countries now ban companies from selling tobacco brands that claim to be “light” or “mild.” There’s no evidence the “lights” are better for your health, he said, so countries have stamped down on companies advertising cigarettes as such.

But Uruguay went one step further.

Philip Morris had tried to sidestep the no-light rule by merely using different colors to distinguish the brands (think: red or gold packaging).

In response, Uruguay then changed its laws again, prohibiting Philip Morris from selling more than one version of each brand of cigarettes (think: Marlboro, plain and simple).

It was this move that Philip Morris took most issue with, said Kelly Henning, director of public health programs at Bloomberg Philanthropies, which provided financial and legal help to Uruguay in the case.

“Uruguay had the single representation, one brand type law, which was unique, and I believe Philip Morris and other tobacco companies saw this as a serious threat,” Henning said.

In its lawsuit, Philip Morris claimed these regulations stifled its intellectual property rights. The company arbitrated the case in the Washington-based International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes, part of the World Bank. The company had demanded that either the regulations be lifted, not be applied to Philip Morris, or that Uruguay pay the company more than $20 million in damages.

The tribunal instead ordered Philip Morris to pay $7 million and other costs to reimburse Uruguay for the case.

Uruguayan President Tabaré Vázquez, an oncologist and longtime smoking foe, spurred the laws that led to the original lawsuit in 2010.

On July 8, he publicly announced Uruguay had won the case. “This can be considered a triumph for all Uruguayans,” Vázquez said in a televised speech.

Read more: Why Uruguay’s David and Goliath fight with big tobacco really matters

Myers said the victory was unequivocal. While the arbitration ruling isn’t binding in other courts, he said the arbitrators sent a clear signal to Big Tobacco: Don’t try to use trade treaties as a channel to attack activist governments that are trying to protect their citizens, because it won’t fly.

Major cigarette corporations have frequently turned to the rather obscure trade treaties as an attempt to protect trademarks and fight anti-tobacco legislation, particularly in developing countries. The industry has even teamed up with countries like Ukraine and Honduras, using their trade agreements with other countries as an avenue to attack anti-smoking laws.

Myers said the Uruguayan decision should put a stop to all that.

“The arbitrators made very clear that countries have a great deal of discretion to enact legislation to address public health issues,” Myers said. “And that the international trade arbitration system isn’t there to second-guess good faith decisions in government.”

Philip Morris released a statement in response to the judgment. It quotes Marc Firestone, the company’s general counsel:

“For the last seven years, we have already been complying with the regulations at issue in the case, so today’s outcome doesn’t change the status quo. We’ve never questioned Uruguay’s authority to protect public health, and this case wasn’t about broad issues of tobacco policy. The arbitration concerned an important, but unusual, set of facts that called for clarification under international law, which the parties have now received. We thank the Tribunal for its assessment and respect its decision.”