Foreign-born citizens in Louisiana have had to take extra steps to register to vote — until now

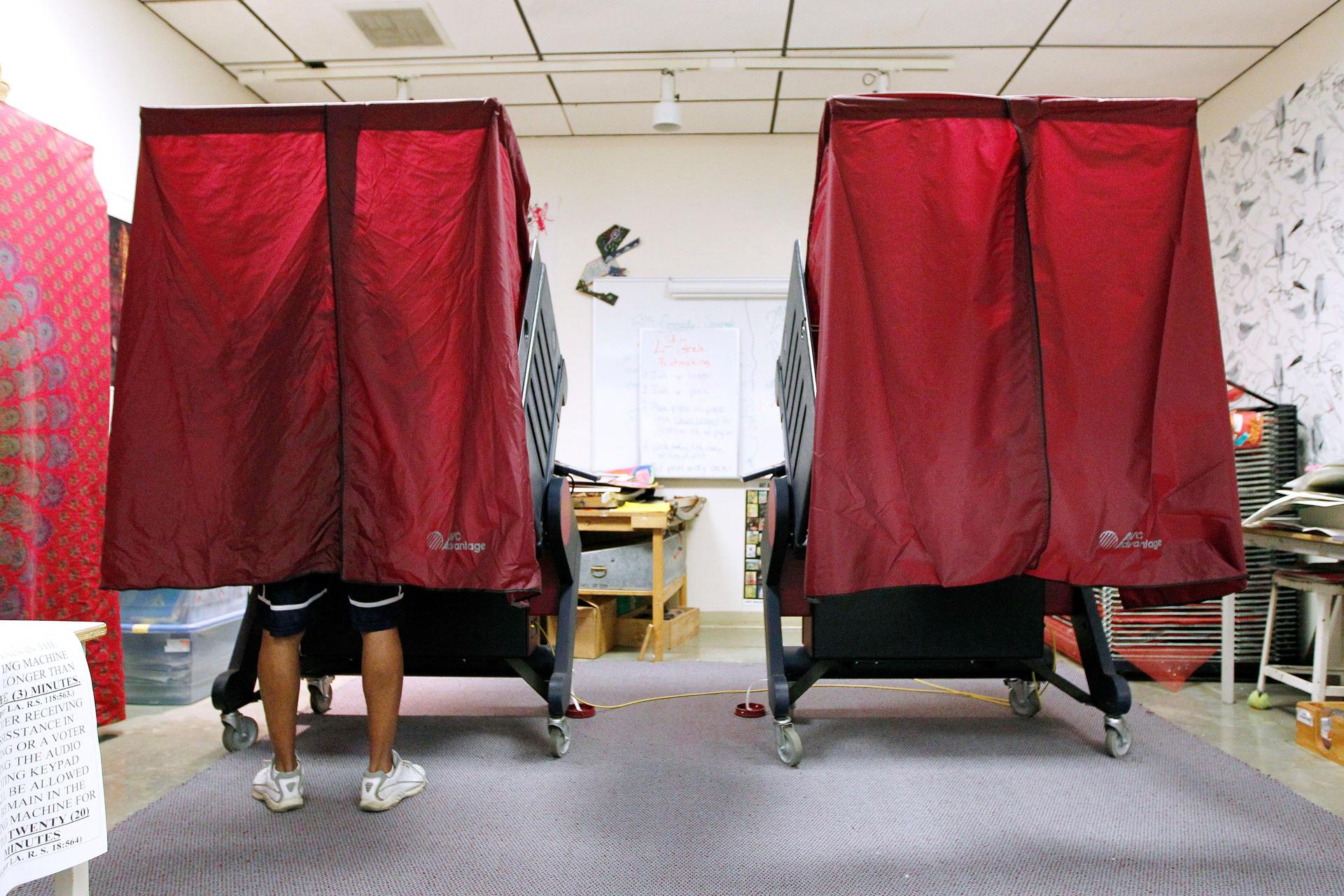

A voter casts his ballot in New Orleans, Louisiana March 24, 2012. Naturalized voters in the state will no longer have to provide proof of citizenship to register in the state. Louisiana was the only state that required only foreign-born citizens to provide proof of citizenship, but four others — Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, and Kansas — require all voters to do so.

Until this week, naturalized citizens in Louisiana were required to go an extra mile to register to vote: After filing a standard registration form, potential voters born outside the US were required to submit proof of citizenship, in person, at their local registrar’s office.

“It felt like we were targeted,” says Tu Hoang, an attorney in Louisiana.

Hoang, 28, emigrated from Vietnam with his parents when he was five. He became a US citizen when he was 19 and registered to vote soon after. He was able to navigate the system without any hiccups, providing proof of citizenship with his voter registration form, but noticed an unsettling shift years later when he was organizing voter registration drives in the Vietnamese community of New Orleans.

Around 2012 the procedure became more cumbersome — a shift other advocates also noticed. The proof of citizenship requirement became more strictly enforced and applicants were required to make an extra trip, several weeks after filing the registration form, rather than submitting both together.

“I don’t think this thing was even really enforced until 2012. Is it because they saw an influx of naturalized citizens wanting to vote?” Huang says. “It sickens me that someone is moving parts around when other people are having to jump through hoops.”

There was no change in policy that spurred the shift, just a change in how it was enforced. Hoang attributes the change to the work of grassroots organizations, such as VAYLA New Orleans where he is a board member, to register naturalized citizens to vote. In post-Katrina New Orleans, he says, community organizing has taken newfound urgency and seen much success.

Carolina Hernandez, executive director of the nonprofit Latino advocacy group Puentes New Orleans, has worked on voter registration drives in New Orlean’s Latino community since 2007. She estimates that nine out of 10 potential voters who are non-native-born declined to register when they learned the process. She found that many people were unable to make it to the registrar’s office during working hours, or were simply deterred by the cumbersome process.

“It’s inconvenient and democracy shouldn’t have to be that hard,” she said.

And now, it won’t have to be. This week, Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards signed a bill that repeals the 142-year-old law.

The change came just four weeks after civil rights groups filed a federal suit demanding the law be repealed. Lawyers who filed the suit were surprised — and relieved — that the case didn’t need to go to court, says Naomi Tsu of the Southern Poverty Law Center, one of the groups who filed the suit.

“It's a better use of taxpayer money than fighting a lawsuit that I'm pretty confident we would have won,” Tsu says. “But I kind of wish they had passed the bill before we had filed.”

The lawsuit was filed on behalf of three naturalized citizens who had collectively attempted to register to vote eight times but failed because of this requirement, and VAYLA. Minh Nguyen, executive director or VAYLA, is the son of two Vietnamese refugees who are now both American citizens.

“Myself and other young folks, we saw it as our role that our parents and grandparents had [to have] the right to vote,” he said.

Over 72,000 naturalized citizens live in Louisiana. The lawsuit says singling out this group for scrutiny to vote amounts to a violation the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment, Title III of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the National Voter Registration Act.

Nationally, as in Louisiana, studies show that naturalized citizens vote at lower rates than those born here. But, a 2012 University of California study suggests that registering to vote is an equalizer: Of registered voters, naturalized citizens and native-born citizens cast ballots at roughly equal rates.

More: What it's like to register to vote in Oregon and Texas

Louisiana was the only state that required only foreign-born citizens to provide proof of citizenship, but four others — Alabama, Arizona, Georgia and Kansas — require all voters to do so. Thirty-three states require state-issued ID to vote, more than double the number that did in 2000, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL). In Louisiana, ID is suggested but not required. Proponents of tightening requirements say it prevents voter fraud. Critics say that poor, elderly and non-native citizens are less likely to have the required identification.

Hernandez is hopeful that voter registration drives leading up to the presidential elections will now be much smoother. But, she says, another part of her job is to see that the repeal is enacted in local registrars’ offices.

“The next step is making sure that there is some accountability, making sure that the registrar’s office is aware of this and that they’re operating in a way that they weren’t before,” she says. “That could take some time.”