Vernon Ichisaka checks the weight of beans picked at Seabrook Farms in 1950. Field laborers had to meet daily quotas on the amount of vegetables they picked. Beginning in 1943, Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II became eligible to work for select companies. Though they were often born in the US, their limited job choices and restricted mobility meant that they were treated like guest workers.

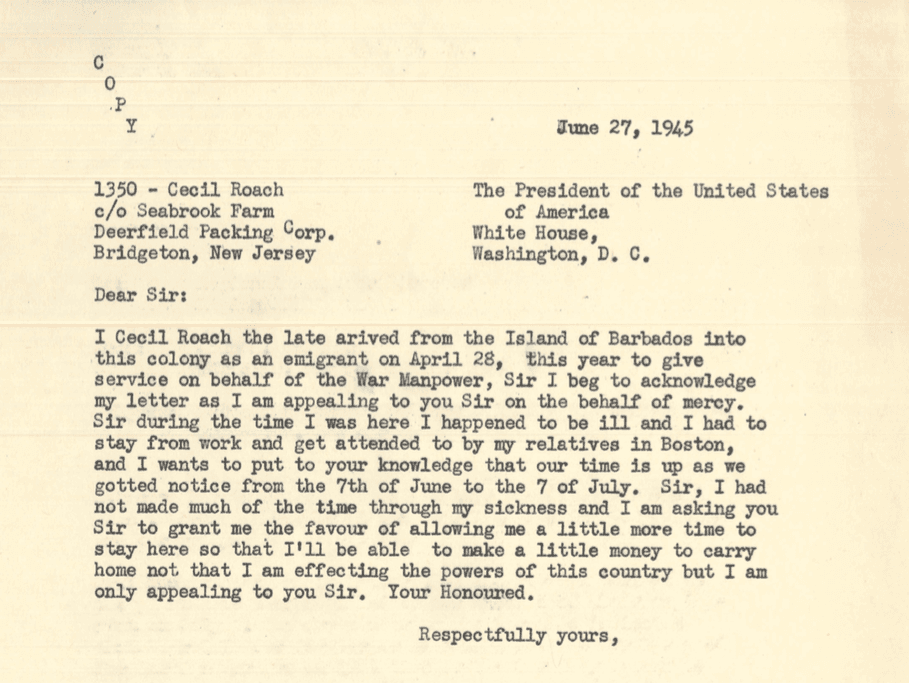

“Sir, I had not made much of the time through my sickness and I am asking you Sir to grant me the favour of allowing me a little more time to stay here so that I’ll be able to make a little money to carry home not that I am effecting the powers of this country but I am only appealing to you Sir.”

This is how Cecil Roach’s June 1945 letter to US President Harry S. Truman, dictated to an unnamed typist, ends.

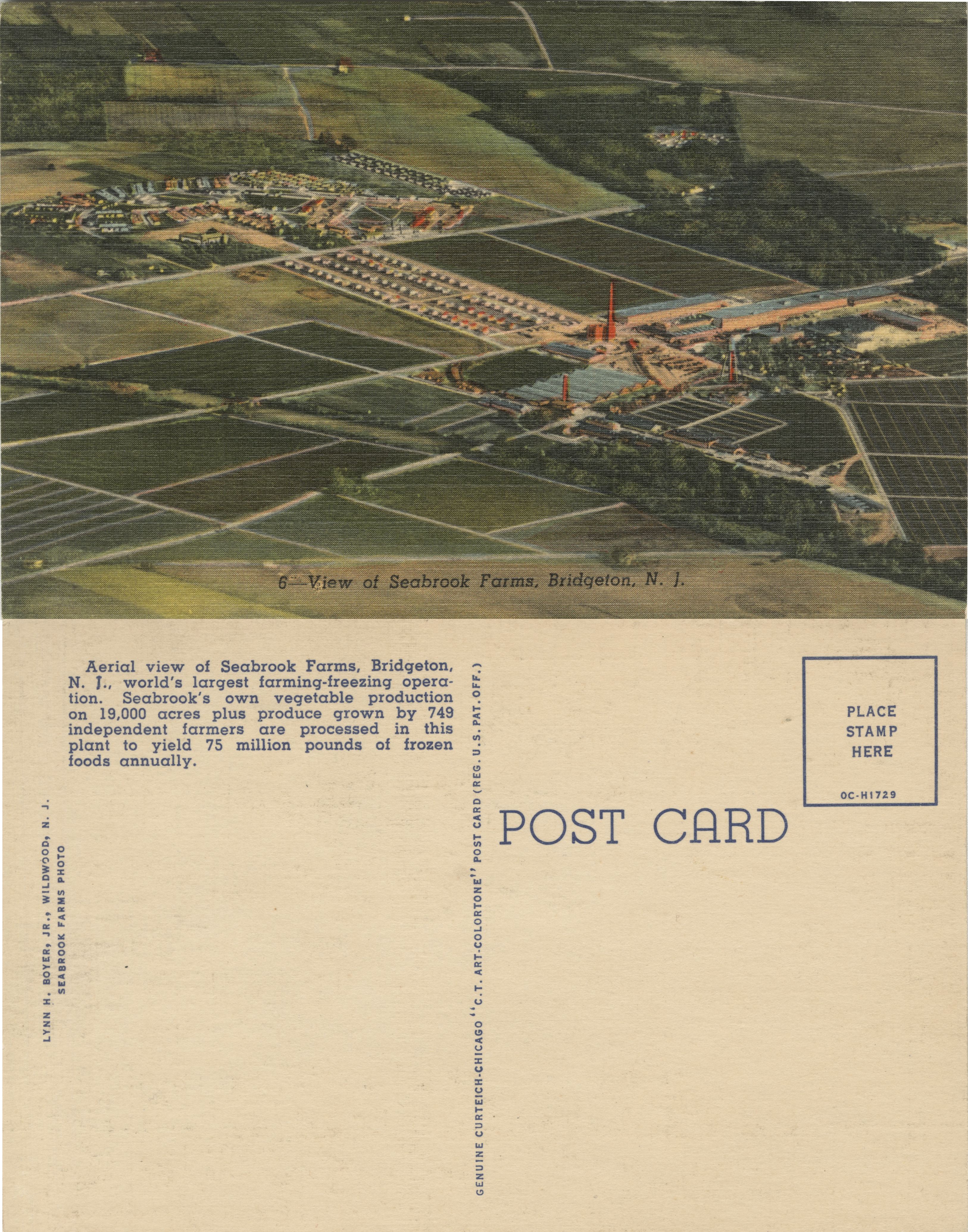

Roach was a guest worker from Barbados recruited by the War Manpower Commission, one of hundreds of British West Indians who came under contract to work at the Deerfield Packing Company, a subsidiary of the agribusiness Seabrook Farms outside Bridgeton, New Jersey. Illness prevented him from working and the company apparently sent him to family members in Boston to recover. Roach was anxious about having to return to Barbados without having earned any money. He did not think that extending his stay would hurt Americans in any way.

He came to the US under the provisions of Public Law 45, passed by Congress in April 1943. It authorized agricultural employers, with the help of the federal government, to hire and import guest workers like Roach from the Caribbean. In the Midwest and West, this same piece of legislation led to the creation of the bracero program, which allowed businesses to recruit Mexican workers on a temporary basis, and overcome labor shortages.

In theory, migrants from Barbados, Jamaica, and the Bahamas were protected by US agreements with the British Colonial Office, which governed the islands as colonial possessions. Upholding wage and living standards, however, proved almost impossible.

Today’s guest worker programs for both educated white collar workers and for agricultural workers are still rife with abuses. The lax enforcement of employment contracts is a major problem for guest workers who, in worst case scenarios, are forced to remain with employers and prevented from either returning home or switching jobs.

In the 1940s and ’50s, guest workers were permitted to remain in the US only if they stuck to the terms of contracts binding them to specific employers. If guest workers left the jobs — whether because of wage disputes, poor treatment, or to seek out higher-paying employment — their names were passed on to immigration officials so they could be tracked down for deportation.

At Seabrook Farms, this was a relatively frequent occurrence. In August 1945, for instance, company officials reported that 20 Barbadian guest workers had “disappeared” from their jobs. They were identified in a list sent to immigration officials and targeted for removal.

Today, while some politicians have called for reforms designed to better protect foreign workers, others have focused on whether guest worker programs harm Americans through unfair job competition.

This was an issue at Seabrook Farms as well. African American workers, who migrated on a seasonal basis to New Jersey from the South, regularly complained that the available supply of West Indian guest workers gave the company leverage to keep wages down and make them disposable.

Guest workers too had many reasons to be dissatisfed.

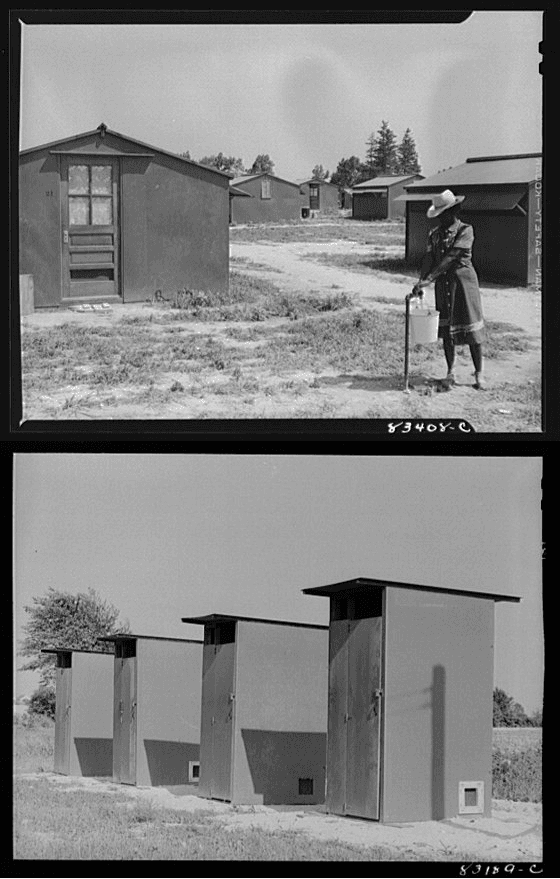

A visitor to Bridgeton in the summer of 1944 would have encountered a series of sprawling migrant labor camps dotting the landscape between the town and Seabrook Farms. The Big Oaks and Orchard Center camps were home to about 1,500 migrant laborers who lived in wooden barracks, shanties and open tents without indoor plumbing, electricity or facilities for storing food. Residents shared communal outhouses.

Reformers from the New Jersey Consumers’ League touring the camps documented outbreaks of diarrhea and typhoid and a complete lack of medical services. They complained that Seabrook was benefitting from the labor of guest workers, without having to assume any responsible for their welfare.

By 1950, the company employed 6,000 workers in its plants and fields during peak production periods. Both its own brand and the Birdseye brand, whose frozen vegetables it produced and distributed under contract, were household names and suburban consumer staples in the postwar years. Its heyday was short lived, however. By the end of the decade the company was sold to the Seeman Brother wholesale grocery corporation. By 1976, the frozen foods plant was closed for good.

During the same years in which West Indian workers were arriving, Seabrook Farms recruited 2,500 Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in camps. These were American citizens of Japanese descent, along with Japanese immigrants, whom the US government classified as wartime national security threats. Even though 60 percent of the 120,000 detainees held in camps were American-born citizens, restrictions on their movement and work options meant they were treated like guest workers brought in from abroad.

Japanese Peruvians were another group of detainees sent to labor at Seabrook. Following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, approximately 20,000 Japanese Peruvians and other Latin Americans were sent to prison camps in the US. When the war ended, Peru refused re-entry to the individuals it had exiled earlier.

Immigration officials in the US declared that Japanese Peruvians were “illegal” aliens, even though they were brought to the country against their will. In 1946, Wayne Collins, a San Francisco-based lawyer, negotiated for approximately 300 Japanese Peruvians, who had been ordered deported to war-destroyed Japan, to be relocated to Seabrook Farms while their appeals were pending.

At Seabrook Farms, Japanese Peruvians were subjected to even stricter controls and surveillance than what Japanese Americans faced. They were forced to remain on the company’s grounds at all times. Because they were not allowed to go to Bridgeton, they could only purchase more expensive consumer goods in the company-owned commissary. The 1952 Immigration and Naturalization Act cancelled deportation orders for Japanese Peruvians who remained in the country. Only then were they allowed to apply for permanent status — and claim the same rights and protections as other workers.

Adding to its diverse workforce, Seabrook Farms also relied on refugees from eastern and central Europe. Estonians living in German camps after they had fled Soviet troops became an important source of labor for Seabrook Farms after the end of World War II.

The 1948 Displaced Persons Act required that refugees have employment and housing before they left for the US. But the government did not want to assume any costs associated with providing public relief to the refugees. As a company town, Seabrook Farms could provide both employment and housing in the same location. The company hired Estonians and other European refugees at 52 cents an hour, below the rate of other workers who were already employed and unionized.

Like the Estonians who came to Seabrook, today’s refugees are migrants who need to earn a living after arriving in the US. It is not coincidental that the meat-packing industry, which features some of the highest rates of on-the-job injuries and working conditions, has become a primary employer of refugees. “Little Somalias” have appeared across the Midwest and companies like National Beef have replaced undocumented workforces, in some cases depleted by immigration raids, with refugees.

More: Immigrants, not locals, are chopping chicken in Missouri

There was one source of labor that Seabrook Farms could not access in the 40s and 50: undocumented immigrants. Today, the threat of deportation greatly effects undocumented workers’ willingness to protest and speak out. Some employers use immigrants’ undocumented status to coerce them into accepting illegal working conditions. Workers have reported being fired and threatened with deportation for asking to be paid minimum wage or after being injured on the job.

Also: Workers may unionize — but not farmworkers. A lawsuit in New York seeks to change that.

This month, the eight sitting justices of the Supreme Court are expected to rule on whether President Barack Obama’s executive action to give temporary relief from deportation to millions of undocumented immigrants will proceed. If the Court rules in favor of the Obama administration, some 5 million undocumented people will also have the chance to have temporary work authorization.

Policymakers who support Obama’s program argue that undocumented laborers will continue to work for low wages even if the deportation danger is lifted. Work permits, they say, will remove employers’ ability to exploit immigrants. Opponents say work permits reward undocumented immigrants’ behavior.

If history teaches us anything, though, it is to appreciate the longstanding tension between employers’ demand for labor and the government’s desire to regulate and control who is permitted to enter the country and under what terms. At stake is whether or not the workers who produce the goods and services that Americans consume are also afforded full protection under the law.

Learn more about the history of Seabrook Farms in “Invisible Restraints: Life and Labor at Seabrook Farms,” online now at the New Jersey Digital Highway. The collection was created by the author and his students at Rutgers University.