The hall outside of Woodburn High School counselor Mario Garza's office is decorated with pennants from colleges and universities across the country.

Last winter, toward the end of her first semester as a college freshman at Oregon's George Fox University, Giselle Lopez-Ixta started keeping a list on her phone.

It’s a running tally of the sorts of the discrimination Lopez-Ixta has seen or experienced since she graduated from her very Latino high school in Woodburn, Oregon and moved 20 minutes down the road to start college at a very white university.

There’s that time a teacher assumed Lopez-Ixta’s friend wasn’t American, because she spoke English as a second language. The time an acquaintance said Woodburn was ‘straight thug.’

And then …

“Food stamps — my family has food stamps and the comment was that we don’t deserve food stamps because we’re lazy,” she says.

Lopez-Ixta is quick to point out that this sort of thing — it’s the exception, not the rule. Still, it’s very different from her experience as a high school student at Woodburn.

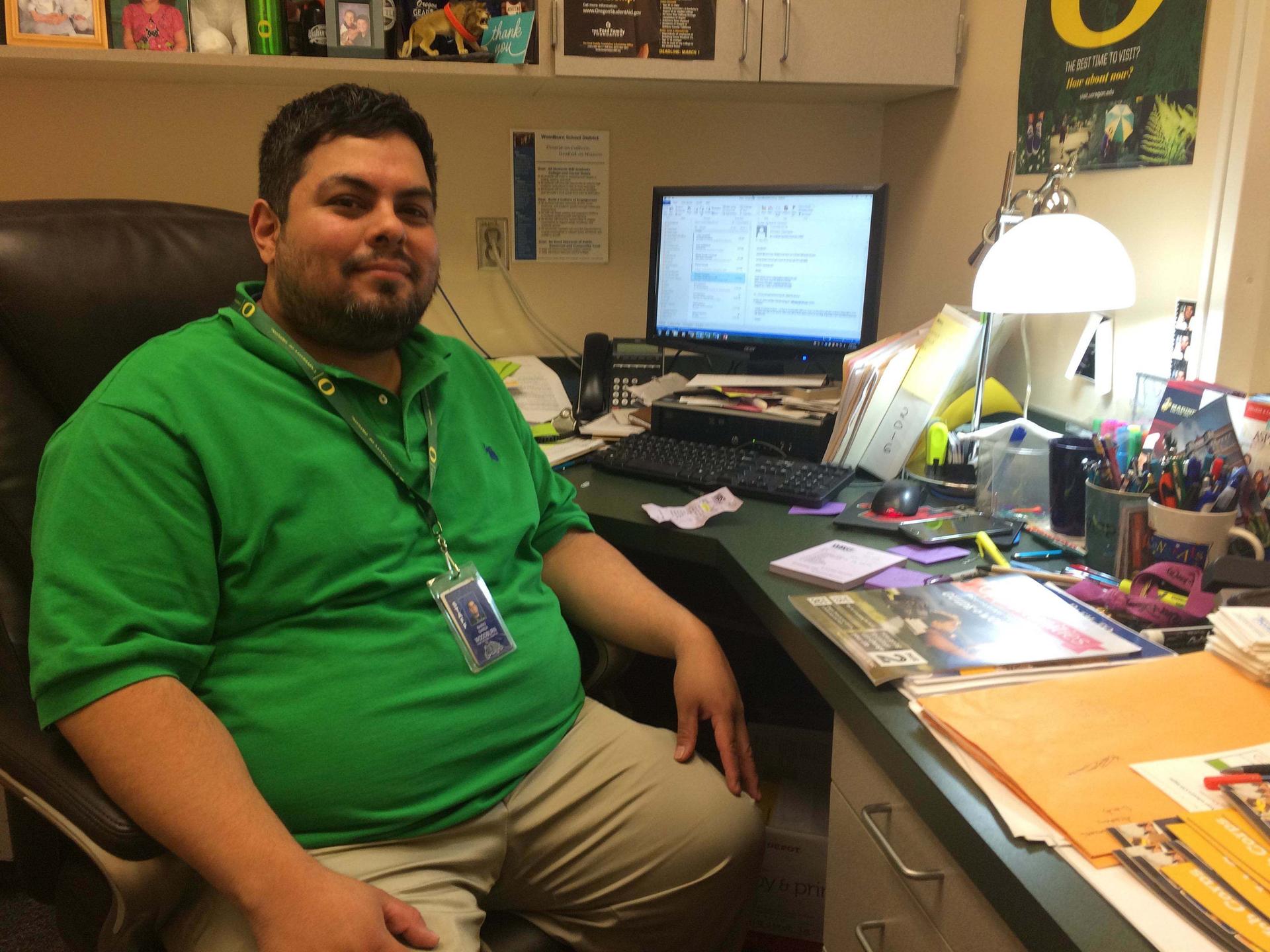

“Woodburn is pretty unique in the state of Oregon,” says Mario Garza, the college and career counselor at Woodburn High. “Our population is about 80-85 percent Hispanic — the vast majority being Mexican immigrants or second and third-generation Mexican Americans.”

Garza says the Woodburn School district goes above and beyond to support those students. Kids get full-fledged bilingual education starting in kindergarten. And the high school’s broken down into four small schools.

“Every teacher and principal on this campus is on a mission to make sure that our kids graduate,” he says. “And even if they’re not making it the first time, second time, need extra help here — they’re willing to put in the extra work to make those things happen.”

This approach seems to be working. For the past two years now, Woodburn has been beating the state’s high school graduation rate — by double digits. But lately, there’s something that’s been bothering Garza.

Earlier this year, Woodburn administrators started getting information from the National Student Clearinghouse. That’s a body that collects data from colleges and universities across the country to track what happens to students after they graduate from high school.

“We had a lot of kids that started school, but we weren’t finding those last pieces where it said they received a degree,” Garza says.

Take, for example, the class of 2008. Out of about 300 students, only 25 went on to receive their bachelor’s degree.

“Oftentimes it’s, ‘I wasn’t comfortable there. It’s not Woodburn. It’s very different,’” Garza says. “And like, well yeah, no one promised you Woodburn.”

Garza thinks Woodburn’s greatest strength might also be its Achilles heel. In this community, kids who would be in the racial and cultural minority elsewhere in Oregon make up the majority. When they leave Woodburn, they’re entering a very different world.

“Many of our students are not finding that place they can call home,” he says. “We’ve seen over the last few years, at least in the data that we have at this point, that a lot of our kids are not succeeding at the level we would want them to in college.”

Deborah Faye Carter has a slightly different perspective. She’s been researching the challenges facing minority students for more than 20 years.

“It might be a cultural bubble, but I might also suggest that colleges and universities don’t have the appropriate support services, financial aid, etc. to keep students in the institution,” Carter says.

Garza says he often tells colleges that they do more than just attract a diverse student body; they also need to put more time, thought and resources into helping students from poorer backgrounds succeed once they get there.

So, he says, does Woodburn High. The school has started coordinating campus tours at colleges across the state so that students can get a better sense of what life outside Woodburn looks like. And this year, he’ll put on the high school’s first-ever pre-orientation orientation.

The goal is to help college-bound seniors learn how to navigate campus resources for minority students before they even get to college.

How do you educate a Global Nation? Read more of our coverage of immigration and education. Then join the conversation in the Global Nation Exchange on Facebook.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!