This school in Israel is opening dialogue among its Jewish, Arab and international students

Jews and Arabs living in Israel have long shared a fragile co-existence.

Arabs make up about 20% of Israel’s population.

But the two communities have in many ways grown up in separate societies — living in separate towns, reading different newspapers and even attending separate schools.

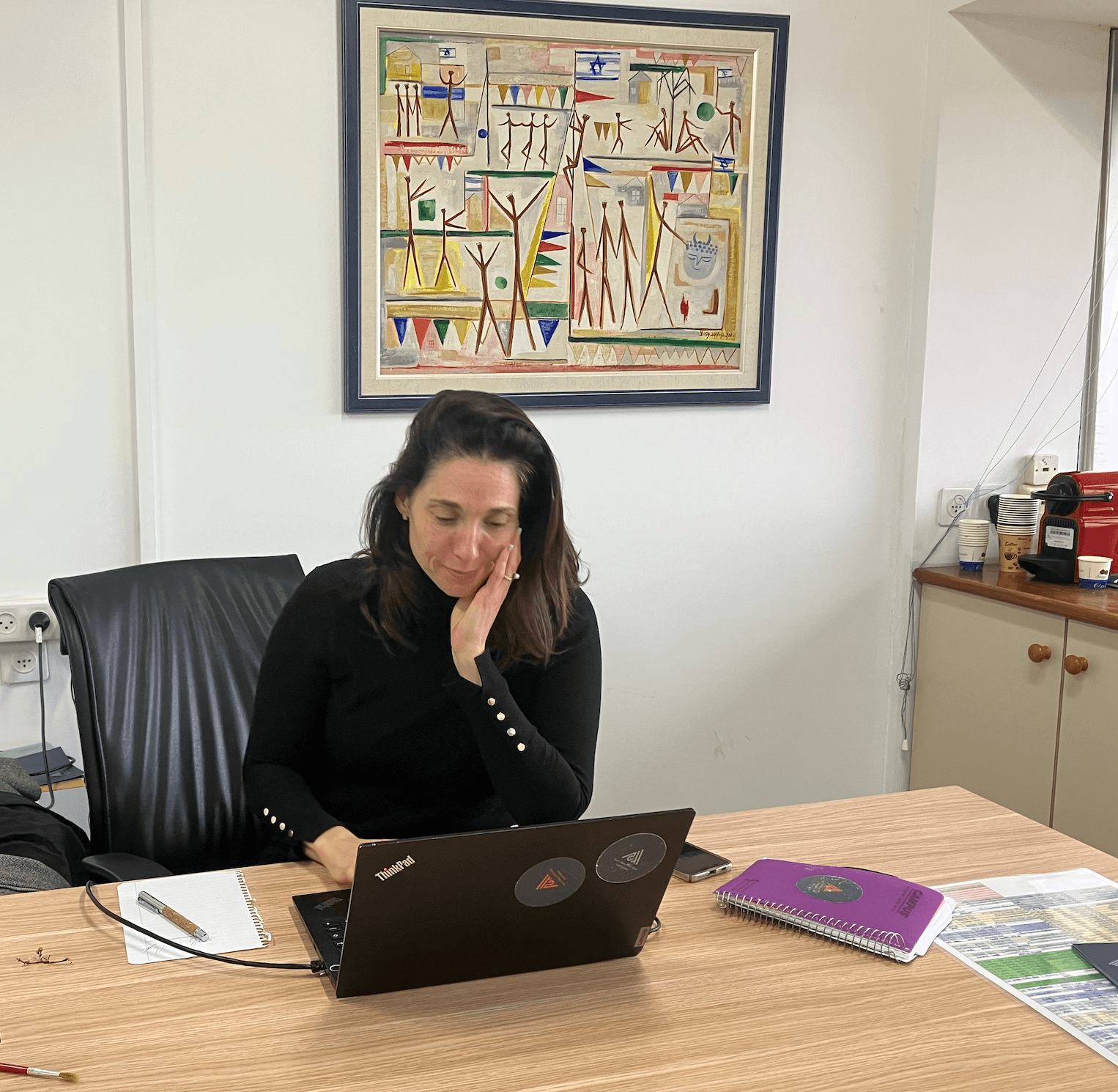

“[Israel] is the only public education system which is segregated by race and religion and ethnicity,” says Michal Sella, the CEO of the Givat Haviva Center for a Shared Society, Israel’s oldest center for Jewish-Arab dialogue.

“The fact that we live so close to each other — sometimes in the same city — and we don’t allow our students to have a normal educational encounter with the other society, means that we have generations growing up thinking that they’re alone here,” Sella said.

“They grow up thinking they don’t need to be sensitive to other narratives, to other histories, to other cultures, to other languages.”

Founded in 1949 as the national education center for a group of kibbutzim, Givat Haviva was among the first organizations to promote reconciliation and inclusion between Jews and Arabs living in Israel.

Six years ago, the center, which for decades has brought in thousands from around Israel and all over the world every year for dialogue sessions, decided to take its mission a step further.

It opened YOUnited, an international high school which today is still one of only a handful of schools in Israel mixed with Jewish and Arab students.

“Our idea is that people will meet people from different places, different cultures, different religions and build themselves and their understanding of the world based on those they meet,” said Nurit Gery, YOUnited’s co-founder and managing director.

Not all of the 150 students at the school are Israeli. About half come from abroad, many from recent conflict zones including Russia, Ukraine and Cambodia.

But the other half are about an even split between Arabs and Jews.

The young experimental school saw its first big test on October 7, when Hamas militants attacked Israel killing 1,200 people.

“It kind of shook things up a bit,” said 17-year-old Nico Ben Jacob, one of the school’s Jewish students.

“We weren’t too sure how to go back into those conversations. But when we came back, when we started sitting with each other again and living together, the conversation was unavoidable. And eventually we realized that we were both just scared.”

Ben Jacob is one of a handful of students who recently spoke with The World.

On a recent afternoon lunch break over falafel and hummus, students admitted feeling shocked, confused — and mostly scared — in those initial days after the attacks.

“I was very scared,” says 16-year-old Angelina Hadad, from an Arab village called Eilabun in northern Israel.

“I told my mom that maybe I don’t want to go back,” she admitted.

“We were all scared together.”

“But when I came, everything was normal between us. We were all scared together. So, we stayed closer.”

Since those first weeks, though, things have become difficult. Especially as the death toll in Gaza continues to rise. Now passing some 29,000, according to the territory’s health ministry.

Ben Jacob is about to enter the military, a requirement for most Jews in Israel. She references a conversation she recently had with an Arab classmate.

“He said, ‘I know that you don’t really have a choice. I just hope that you remember what we talk about when you’re in this position as a soldier.’”

“And this is my intention. I plan to use everything that I’ve learned about the Arab community to not look at them as the other side, to not look at them as enemies.”

The students and teachers here acknowledge they’re in a sort of bubble, separated from the real world.

Which may be why they say they don’t like what they see as black-and-white narratives coming from the news and on social media.

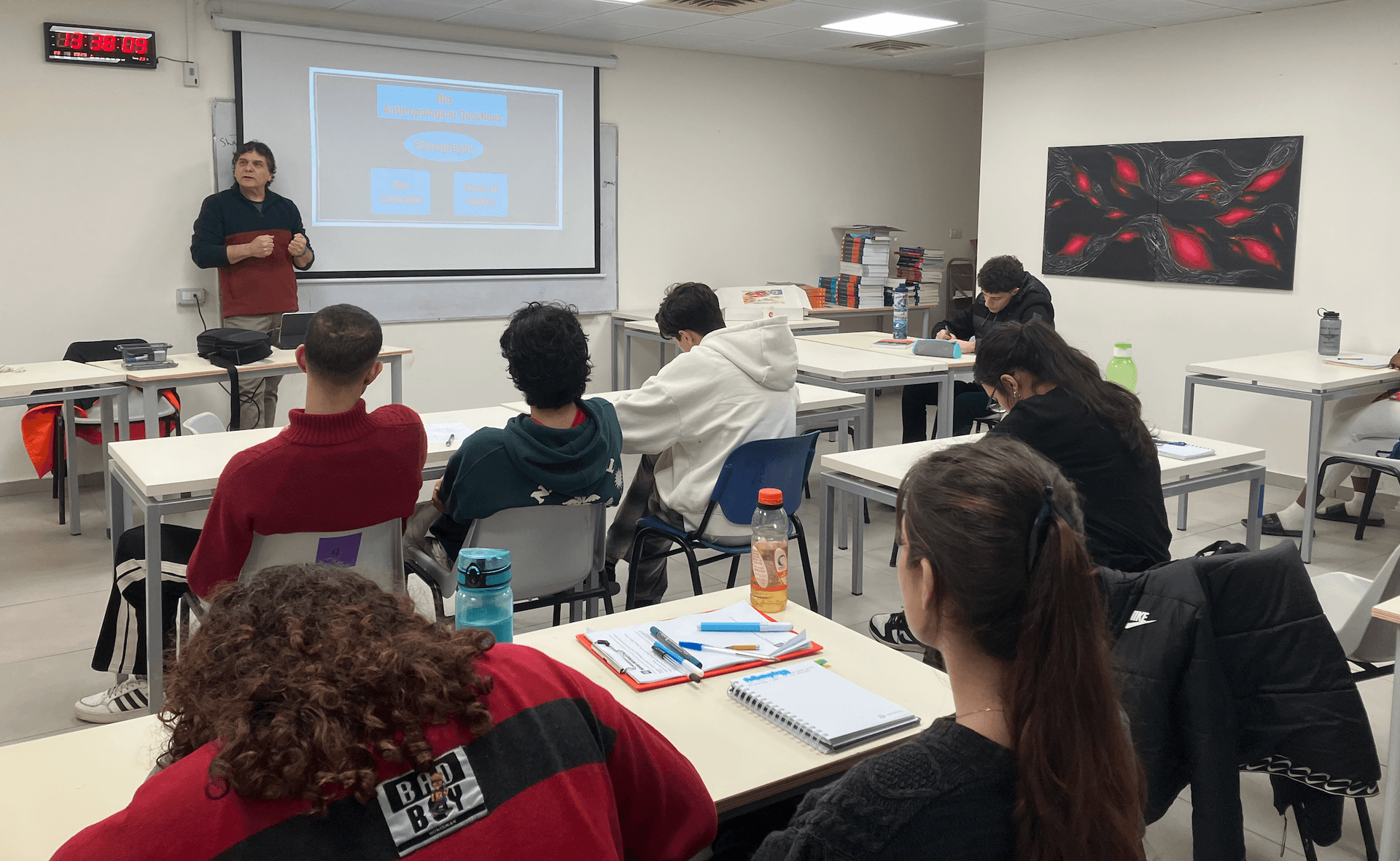

“Everything is about stereotypes now,” said Yuval Dvir, YOUnited’s principal.

“When you open social media, when you open media in general newspapers, you usually see very specific, limited perspectives, narrow perspectives.”

One of the biggest challenges Dvir sees for YOUnited’s students is being able to balance the black and white with the shades of gray they encounter on campus.

“They have to hold perspectives at once and somehow balance in between them. And when you have stereotypes, it’s even harder to do that.”

Dvir says despite recent setbacks for what’s called the shared society movement, he still believes the only way to meet that challenge is through dialogue.

The staff and students at the school don’t like to use the word “coexistence” when they talk about the future.

Instead, they say they envision an Israel which is a “shared society.”

“I think our democracy is really dependent on this idea,” Sella said.

“The Jews are not going anywhere. The Arabs and Palestinians who are citizens of Israel are not going anywhere. We’re going to live together as Israelis.”

Related: Standing Together leaders discuss attempts to open Jewish-Arab dialogue amid Gaza war