Why it matters that the Kansas governor stopped resettling refugees

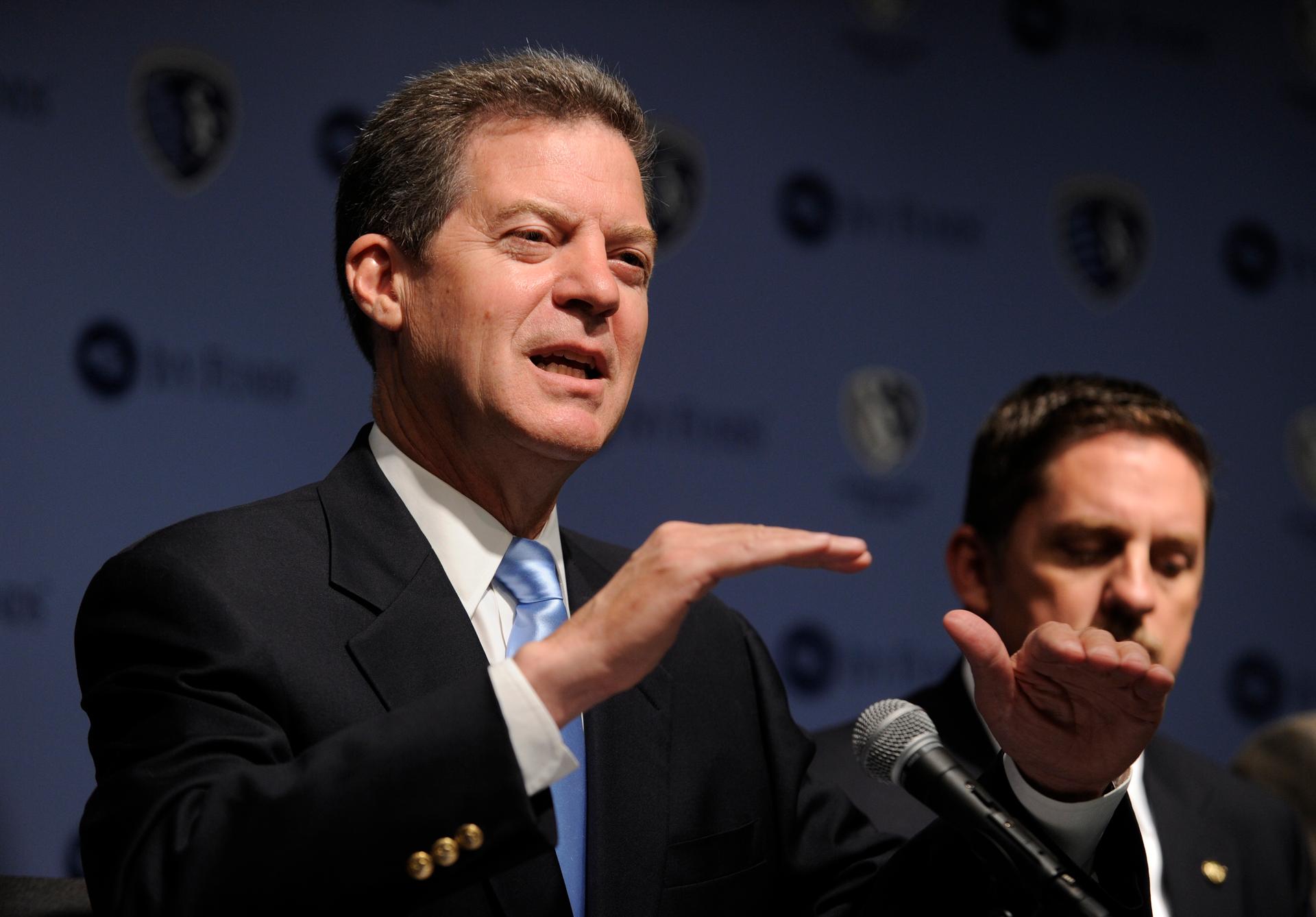

Kansas Gov. Sam Brownback at a news conference in 2014. He announced earlier this week that he will end his state's participation in federal refugee resettlement programs.

When Kansas Gov. Sam Brownback announced earlier this week that he was ending the state's participation in the federal refugee resettlement program, he likely wasn't thinking of refugees like Sonia Inamugisha.

Inamugisha, 34, isn't a Syrian refugee — the focus of Brownback's contentious back-and-forth with the feds in the last several months. She's a devout Christian from the Democratic Republic of Congo and the mother of three children, a six-year-old boy and two girls, 12 and 10 years old. She also won't be directly affected by his announcement — she arrived as a refugee in 2013, and doesn't receive any services from the state and works fulltime as a patient care coordinator at a clinic in Wichita.

Even newly arrived refugees will continue to receive services, such as temporary housing, medical and cash assistance. The US Department of Health and Human Services will transition to administering the funds through a private contractor now that the state is removing itself from the program.

Still, the news hit Inamugisha hard. She had a long and hard journey to get to Kansas. Now she worries about what the governor's decision says about her new home.

“How are you going to be somewhere when you know the government in that area doesn't like you?” she asks. “If the government itself doesn't like you and doesn't want you to be there, what protection are you going to have?”

Inamugisha fled violence in her home country at the age of 23. By then, both her parents and her brother had already been killed. Her ethnic group, the Banyamulenge or Tutsi Congolese, was one faction in a multi-sided conflict that has caused an estimated 5.4 million deaths since 1998.

When she and other family members fled their home near Goma, they had to walk for days before they reached the border with Uganda where they were then put in crowded refugee camps. She spent eight years in those camps and doesn't like to talk about what life was like there. Eventually her asylum application was processed by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees and she was able to make it through the US's refugee screening process, which includes multiple interrogations and background checks from the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security and the State Department. It took eight years and about eight interviews before she was greeted by the International Rescue Committee in Wichita.

Also: How does the US government vet Syrian refugees? Very carefully.

Since she arrived three years ago, Inamugisha has been following the political debate in the US closely. She understands concerns about how best to screen refugees. Many, like her, are forced to flee so quickly that they don't bring much documentation with them, or they come from failed states that don't have dependable recordkeeping. Inamugisha says she left her home running for her life with the clothes on her back. She didn't carry a passport or ID.

“It's not like all refugees are bad. But welcoming them through government makes them have peace. The government back there wasn't able to protect me, and when I come here, the government doesn't want to help me. Why am I coming, and why am I not welcome in this country, or in this state?”

Inamugisha's fears are shared by people who work in the refugee resettlement field.

Jennifer Doran is the executive director of the Wichita office of the International Rescue Committee. The IRC is one of the nine agencies that partners with the State Department to resettle refugees across the country. Since 2002, more than 4,200 refugees have been resettled in Kansas. While the refugees have ended up in 25 different towns, most have settled in Wichita or Garden City, says Doran. (The top five countries of origin are Burma, Bhutan, Iraq, Somalia and Democratic Republic of the Congo, according to the State Department.)

Like Inamugisha, Doran thinks Brownback's move will be felt by refugees across the state.

“The state's partnership with the federal government is important because it sends a message to refugees that they are welcome here. It sets a tone in the state and it can impact upon the local community's perceptions about who refugees are why we have a moral obligation to serve them,” she says. “This is their new home. Refugees have waiting a long time to find a new home and they are excited to join our communities and have a new place where they can feel safe and secure and start planning and thinking about the future.”

More: Canada is just better at welcoming Syrian refugees, but the US is trying to do more

The governor's office sees the situation differently.

To understand how Kansas came to withdraw from refugee resettlement, it's important to review the dance the state and federal government have been having over the issue since November. The exchange is documented in a collection of letters released by Brownback's office when they announced their decision on Tuesday. The dueling correspondences can be technical at times, but the issues discussed have far reaching implications.

On Nov. 20, Brownback issued an executive order compelling state agencies to refuse to provide services to any Syrian refugees. In the face of criticism that it was unconstitutional on both the state and federal level to discriminate against people based on their nationality, Brownback followed with another directive in January saying that agencies should instead deny services to refugees from countries considered by the State Department to be state sponsors of terrorism. That list includes three countries: Iran, Sudan and Syria. Kansas is currently being sued by the National Immigration Law Center over the measure.

“The primary problem is gaps in information because there is no reliable government in those failed nations to confirm that anyone leaving that country is who they say they are,” says Eileen Hawley, communications director for the governor.

The state agencies followed the directive and denied services to two Syrian refugees, one of whom had applied for medical assistance, according to documents. The Office of Refugee Resettlement, which is part of the US Department of Health and Human Services, then wrote an Kansas official and stern letter saying that, among other things, the Civil Rights act of 1964 prohibits programs administered with federal funds from discriminating based on “race, color or national origin.”

Brownback, meanwhile, has consistently demanded that the federal government share all files pertaining to refugees cases. The State Department refused, arguing that federal regulations prohibit the sharing of an individual's information in the asylum process with third parties, with the only exception being counterterrorism partners. Eventually, they hit an impasse: The State Department wrote to the governor saying that Kansas either needed to follow the rules, or leave the program so a contractor could take over for the state in resettling refugees.

Brownback decided to take the feds up on their offer.

“This is about Kansas not actively participating in a program that we believe could put Kansans at risk. It's that simple,” says Hawley.

Sandrine Lisk, director of the Immigration Advocacy Network in Wichita, sees a different motive at play.

“This withdrawal actually has no impact on where refugees get settled by the federal government or those who are already here. Some refugees could move here from New York, or Missouri or Oklahoma,” she says. “Gov. Brownback has no say over that. Other than pandering to his base — to say he's talking tough on terrorism and he's trying to protect Kansans, which he's not — this doesn't even make any sense.”

The debate over refugee resettlement in Kansas seems far from over. Inamugisha, meanwhile, who made it here after such a hard journey, is still trying to figure out how she is going to explain to her children the attitude of her new home.

“I don't know how I'm going to start. They are going to tell me, mom, what should we do, what's next? They are going to have a lot of questions and I don't have answers for that. And when they find out — and I know they are going to find out very soon, TV news is going to talk about that — that may cause a lot of stress, pressure, everything.”