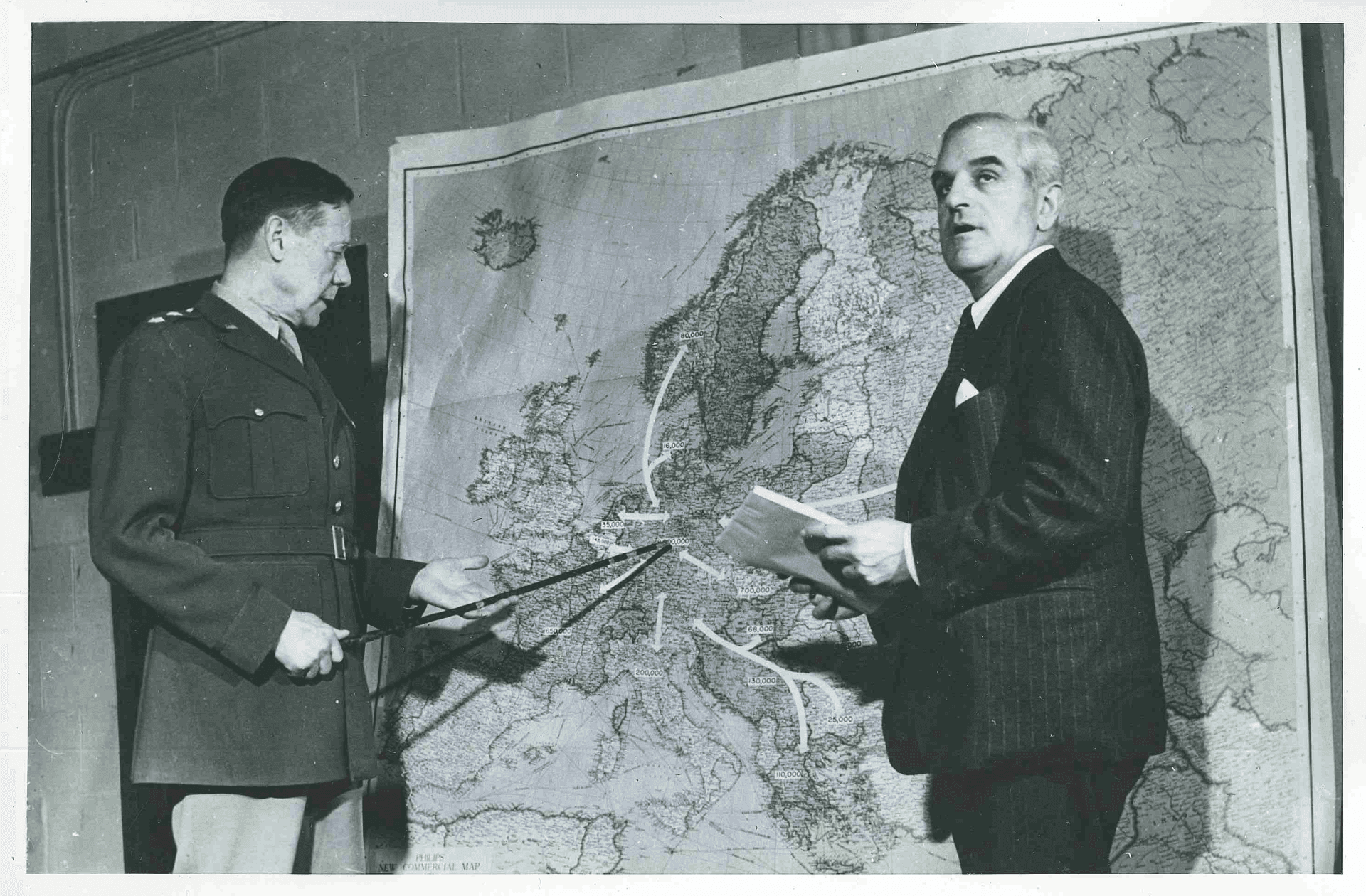

US Army General Allen Gullion and Fred K. Hoehler, Director of the United Nation’s Division of Displaced Persons, stand before a map predicting the movement of European refugees of World War II. Many Europeans would find a haven in refugee camps in the Middle East.

Since civil war erupted in Syria five years ago, millions of refugees have sought safe harbor in Europe by land and by sea, through Turkey and across the Mediterranean.

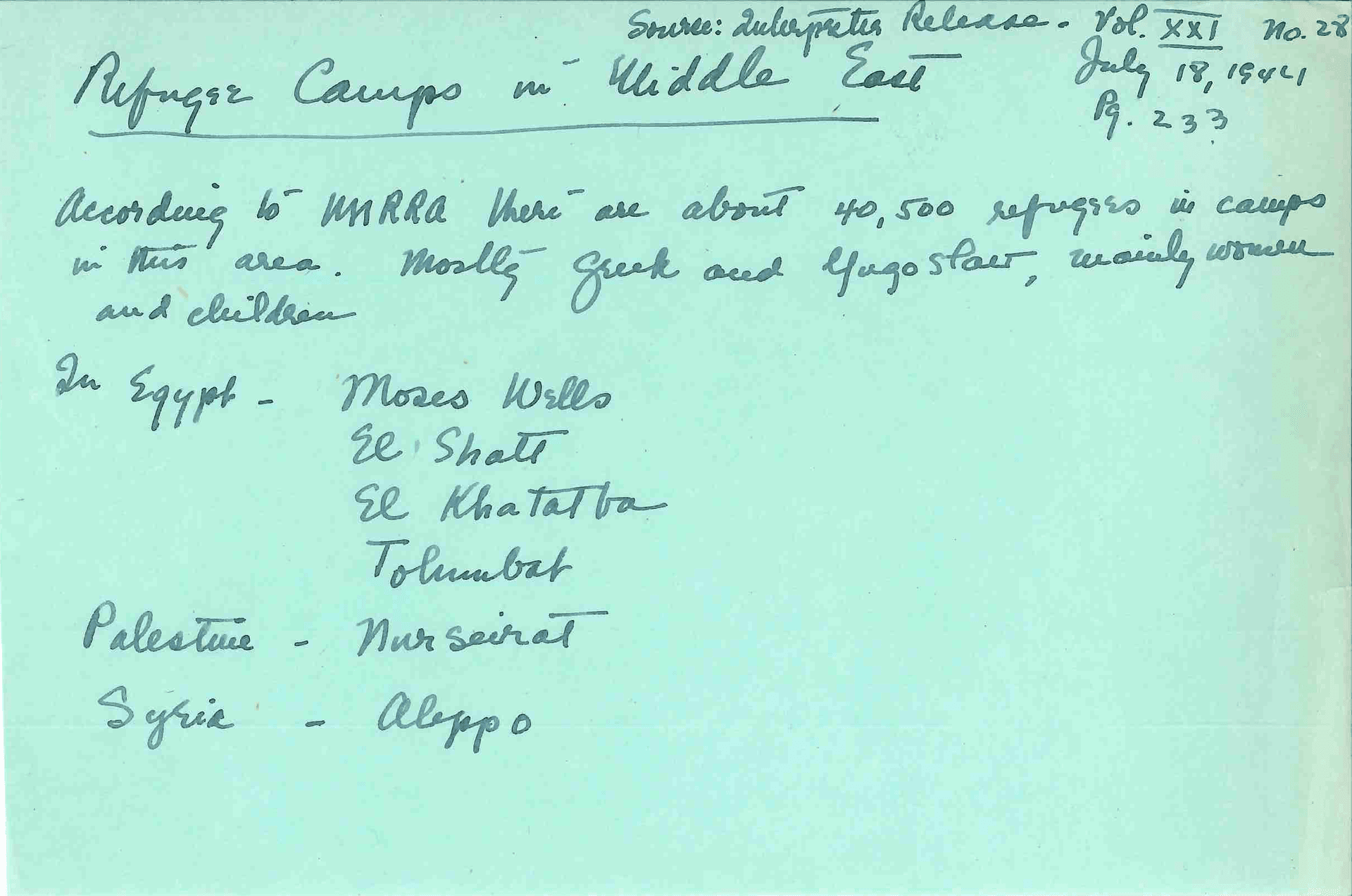

Refugees crossed these same passageways 70 years ago. But they were not Syrians and they traveled in the opposite direction. At the height of World War II, the Middle East Relief and Refugee Administration (MERRA) operated camps in Syria, Egypt and Palestine where tens of thousands of people from across Europe sought refuge.

MERRA was part of a growing network of refugee camps around the world that were operated in a collaborative effort by national governments, military officials and domestic and international aid organizations. Social welfare groups including the International Migration Service, the Red Cross, the Near East Foundation and the Save the Children Fund all pitched in to help MERRA and, later, the United Nations to run the camps.

The archival record provides limited information on the demographics of World War II refugee camps in the Middle East. The information that is available, however, shows that camp officials expected the camps to shelter more refugees over time. Geographic information on location of camps come from records of the International Social Service, American Branch records, in the Social Welfare History Archives at the University of Minnesota.

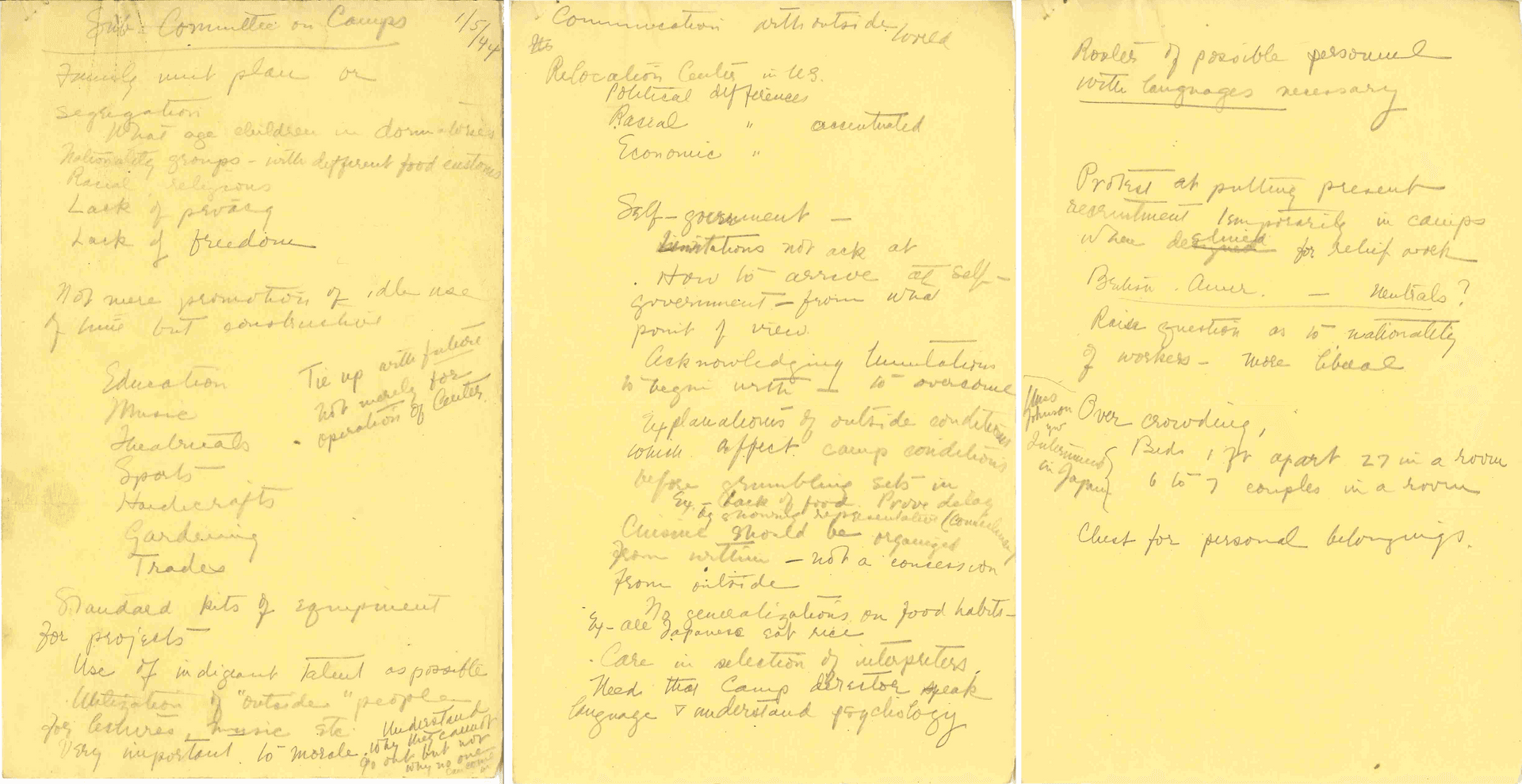

In March 1944, officials who worked for MERRA and the International Migration Service (later called the International Social Service) issued reports on these refugee camps in an effort to improve living conditions there. The reports, which detail conditions that echo those faced by refugees today, offer a window into the daily lives of Europeans, largely from Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Turkey and Yugoslavia, who had to adjust to life inside refugee camps in the Middle East during World War II.

Upon arriving at one of several camps in Egypt, Palestine and Syria, refugees first had to register with camp officials and receive camp-issued identification cards. These identification cards — which they had to carry with them at all times — included information such as the refugee’s name, their camp identification number, information on their educational and work history and any special skills they possessed.

Camp officials maintained a log that recorded the identification number, full name, gender, marital status, profession, passport number, special comments, date of arrival — and eventually, their date of departure.

Some refugees — such as Greeks who arrived in the Aleppo camp from the Dodecanese islands in 1944 — could expect medical inspections to become part of their daily routine.

After medical officials were satisfied that they were healthy enough to join the rest of the camp, refugees were split up into living quarters for families, unaccompanied children, single men and single women. Once assigned to a particular section of the camp, refugees enjoyed few opportunities to venture outside. Occasionally they were able to go on outings under the supervision of camp officials.

When refugees in the Aleppo camp made the several-mile trek into town, for example, they might visit shops to purchase basic supplies, watch a film at the local cinema — or simply get a distraction from the monotony of camp life. Although the camp at Moses Wells, located on over 100 acres of desert, was not within walking distance of a town, refugees were allowed to spend some time each day bathing in the nearby Red Sea.

Those who were fortunate enough to have some money could buy beans, olives, oil, fruit, tea, coffee and other staples from canteens in the camp or during occasional visits to local shops, where in addition to food they could buy soap, razor blades, pencils, paper, stamps and other items. Camps that weren’t pressed for space were able to provide room for refugees to prepare meals. In Aleppo, for example, a room was reserved in the camp for women to gather and make macaroni with flour that they received from camp officials.

Some, but not all, camps required refugees to work. In Aleppo, refugees were encouraged, but not required, to work as cooks, cleaners and cobblers. Labor wasn’t mandatory in Nuseirat, either, but camp officials did try to create opportunities for refugees to use their skills in carpentry, painting, shoe making and wool spinning so that they could stay occupied and earn a little income from other refugees who could afford their services.

Meanwhile, at Moses Wells, all able-bodied, physically fit refugees were required to work in a variety of occupations. Most worked as shopkeepers, cleaners, seamstresses, apprentices, masons, carpenters or plumbers, while “exceptionally qualified persons” served as school masters or labor foremen. Women performed additional domestic work like sewing, laundry, and preparing food on top of any other work they had.

Some camps even had opportunities for refugees to receive vocational training. At El Shatt and Moses Wells, hospital staff was in such short supply that the refugee camps doubled as nursing training programs for Yugoslavian and Greek refugees and locals alike.

In an article for the American Journal of Nursing, as well as in several reports she issued to the International Migration Service, a prominent nurse practitioner named Margaret G. Arnstein observed that students in the program were taught practical nursing, anatomy, physiology, first aid, obstetrics, pediatrics, as well as the military rules and regulations that governed camps. Because most had no formal education beyond grammar school, Arnstein noted that nursing curriculum was taught “in simple terms” and emphasized practical experience over theory and terminology.

The head nurses of the training program hoped they could eventually garner formal accreditation so that anyone who finished the program would be licensed to practice nursing after leaving the camps — at the time, nursing students in refugee camps were only able to treat patients because they were “emergency nurses” operating by necessity in wartime.

MERRA officials agreed that it was best for children in refugee camps to have regular routines. Education was a crucial part of that routine. For the most part, classrooms in Middle Eastern refugee camps had too few teachers and too many students, inadequate supplies and suffered from overcrowding. Yet not all the camps were so hard pressed. In Nuseirat, for example, a refugee who was an artist completed many paintings and posted them all over the walls of a kindergarten inside the camp, making the classrooms “bright and cheerful.” Well-to-do people in the area donated toys, games, and dolls to the kindergarten, causing a camp official to remark that it “compared favorably with many in the United States.”

When they weren’t working or going to school, refugees took part in various leisure activities. Men played handball and football and socialized over cigarettes — occasionally beer and wine, if they were available — in canteens inside the camp. Some camps had playgrounds with swings, slides and seesaws where children could keep themselves entertained, and camp officials, local troops, and Red Cross workers hosted dances and put on the occasional performance for camp residents.

Like today’s refugees, Europeans who found themselves in Middle Eastern refugee camps sought a return to regular life. The people who ran the camps wanted the same. According to the UN Refugee Agency, there are almost 500,000 Syrians registered as refugees in camps today. Almost 5 million people have been displaced by the conflict there.

This story was produced with the help of Linnea Anderson, archivist of the University of Minnesota’s Social Welfare History Archives, who provided special access to and permission to reproduce the International Social Service, American Branch records that serve as the documentary basis for the accounts of refugee life. It was produced in partnership with the Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!