Photos from space reveal a moonscape wrought by geologic forces and celestial bombardment

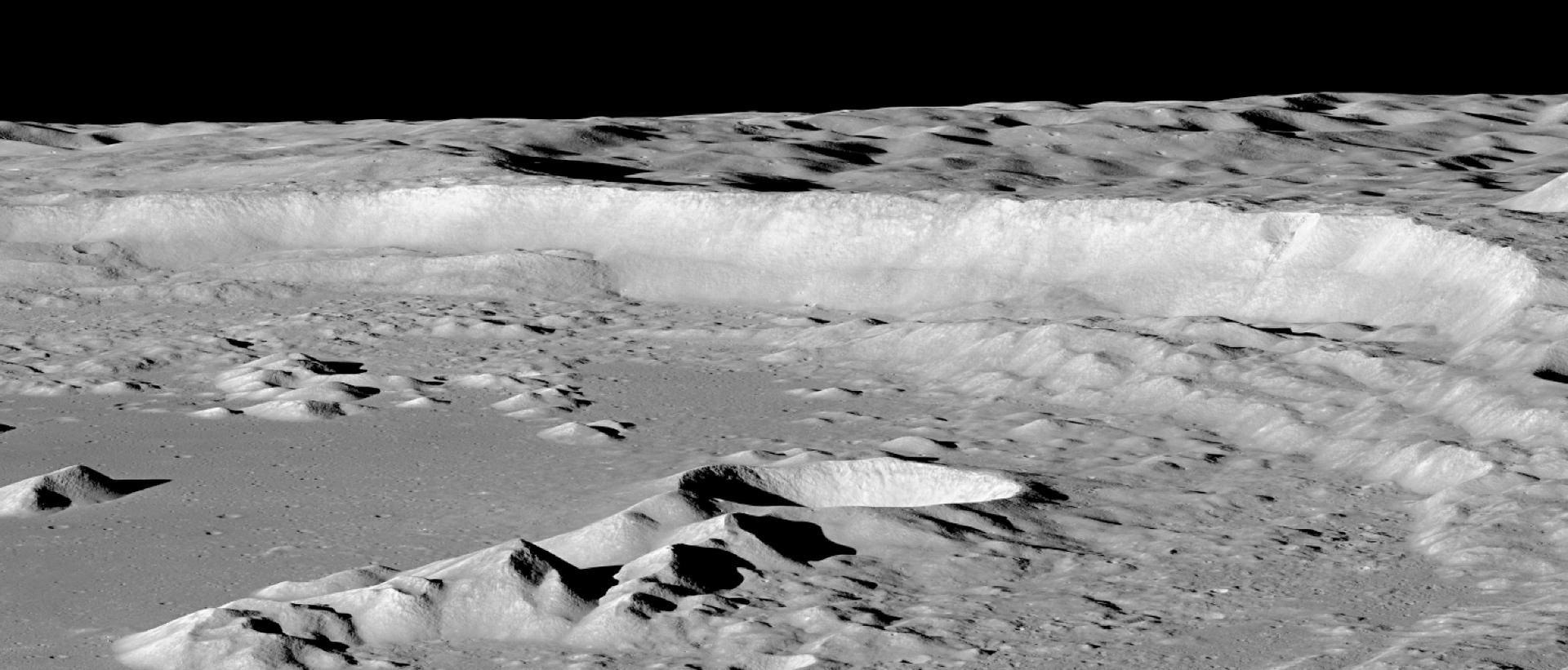

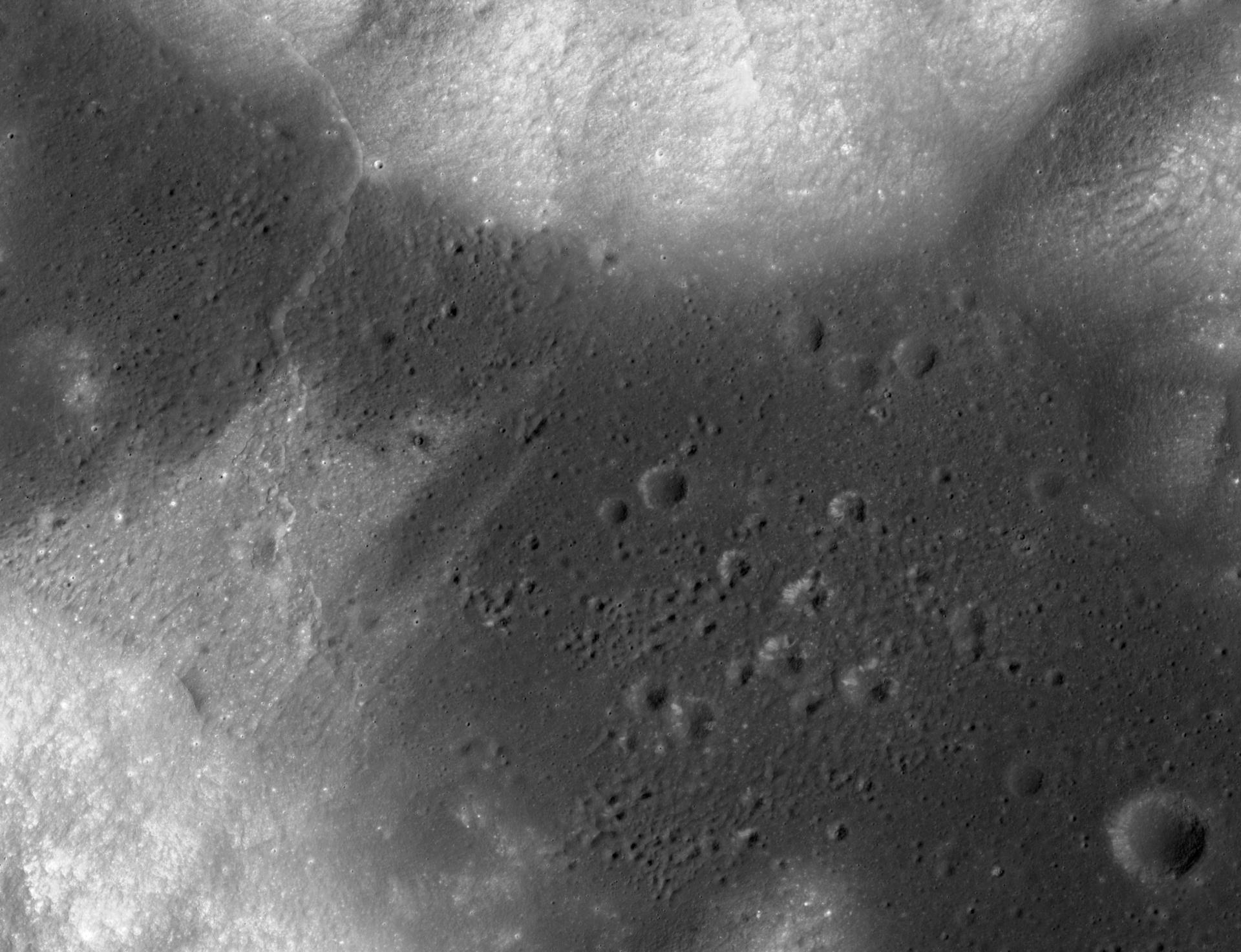

A scene from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter reveals the moon’s rugged terrain. The cliff in the background is the east wall of Antoniadi crater, rising 2.5 miles high. The bottom of the small bowl-shaped crater in the foreground is the lowest point on the moon, plunging more than 5.4 miles below the lunar equivalent to sea level.

From a terrestrial vantage point, the moon seems like a pretty calm and predictable neighbor, following through on its phases and reliably pulling on our tides. But if you start rummaging around in the moon’s business, drama unfolds.

For the past six-plus years, cameras on a spacecraft called the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter have zoomed in for a better look at our celestial companion, snapping thousands upon thousands of photos — many of which reveal, in more detail than ever before, a dynamic moonscape. A selection of that pictorial trove is now on display through December at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, in an exhibit called “A New Moon Rises: Views from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera.”

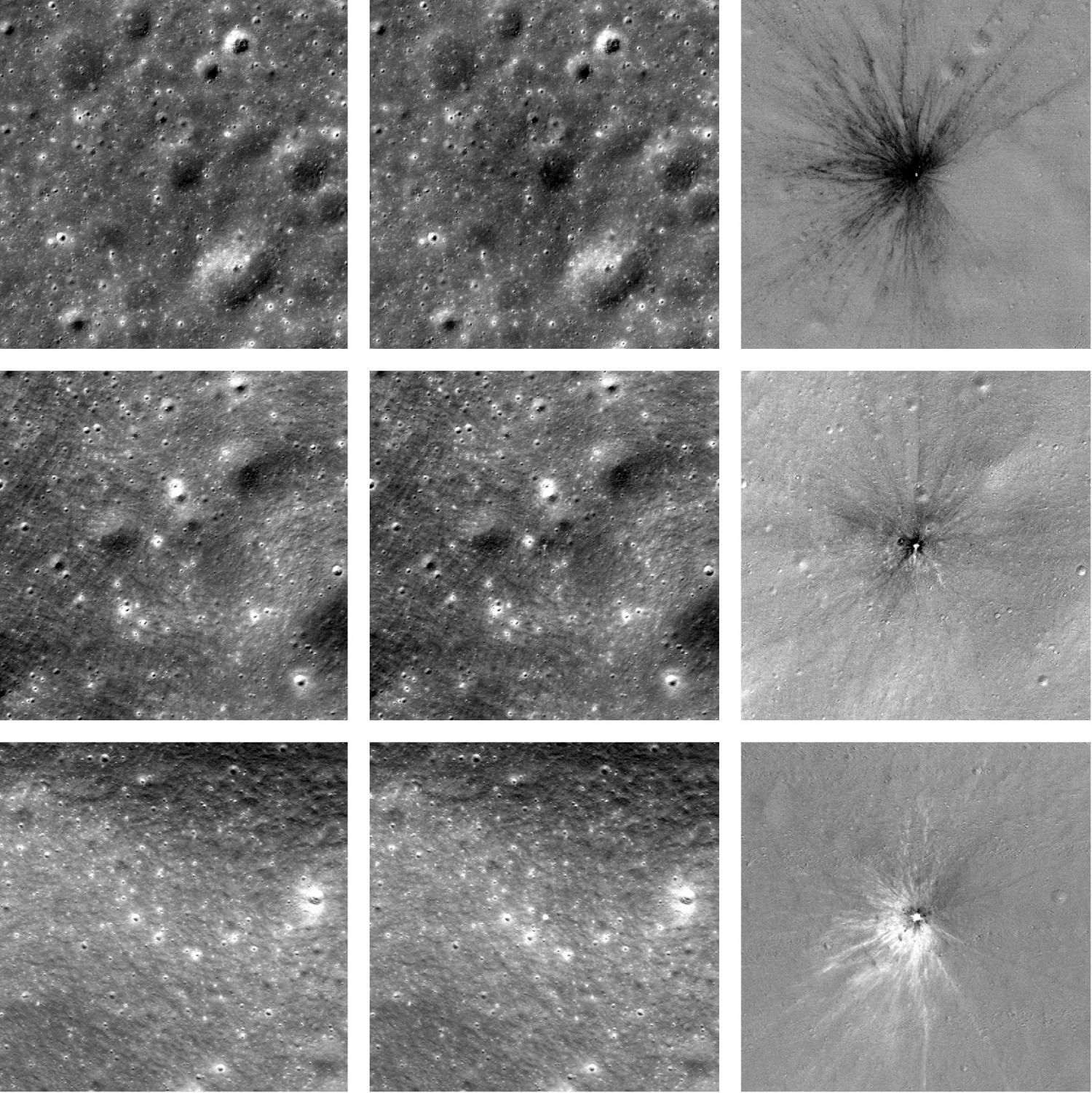

Scars regularly left by space debris speak to the activity occurring on the moon. “We’ve found hundreds of impact craters that have formed just since LRO has been in orbit,” says Thomas R. Watters, exhibit curator and senior scientist at the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the museum, and a co-investigator for the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera.

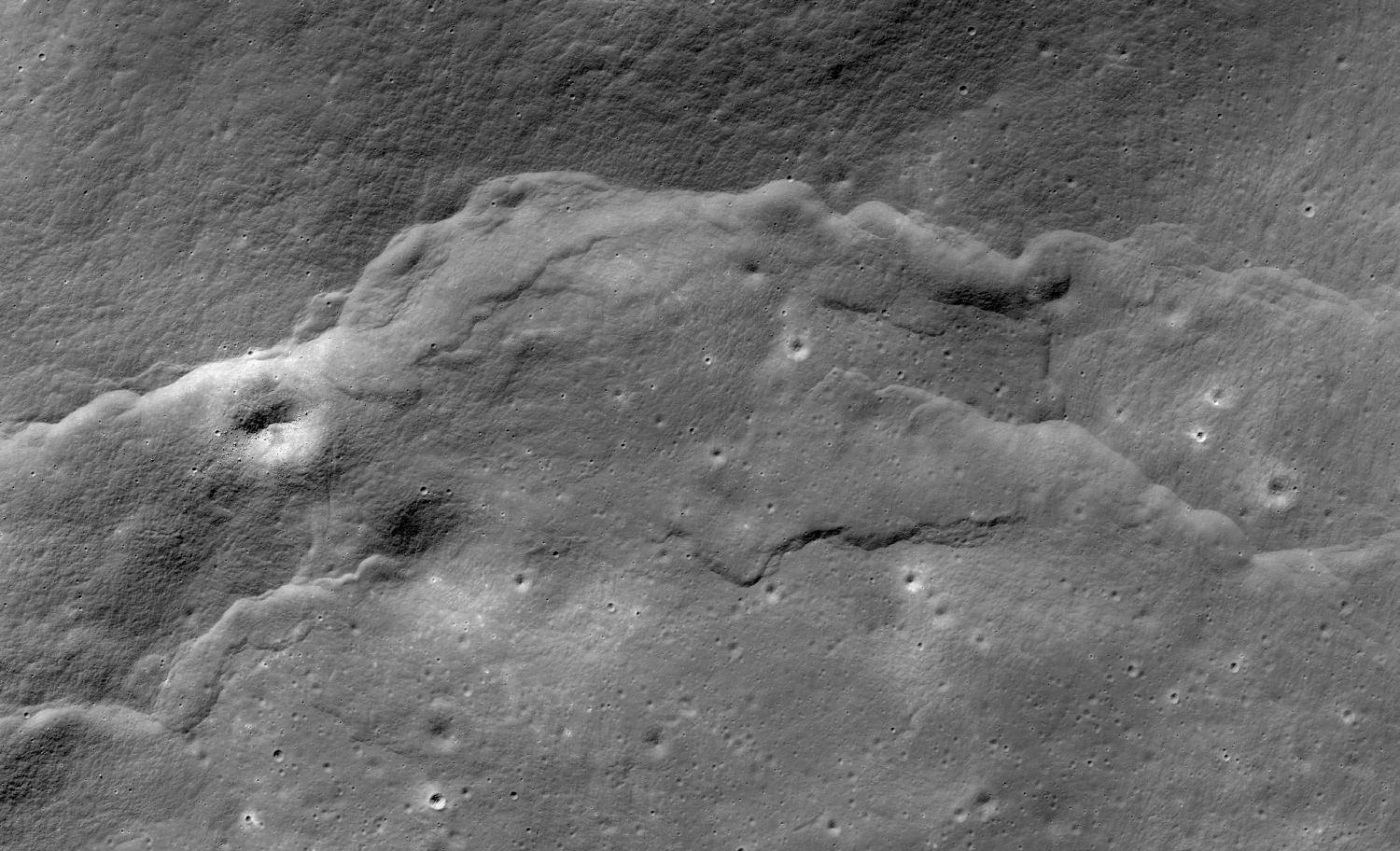

There are also signs of recent volcanic activity.

“The conventional wisdom had been that all the volcanic activity on the moon had ended over a billion years ago,” says Watters, but the orbiter’s cameras have captured evidence of small volcanic deposits that are “probably no older than 100 million years, and they may even be younger than that.” (The moon itself is about 4.5 billion years old.)

Launched in 2009, the orbiter's initial mission entailed assessing sites for a possible human mission and gathering scientific data on radiation and potential ice deposits. Its mission has since been extended to allow for even more ground-tracking. The spacecraft is equipped with a suite of instruments, including two telescopic cameras — each capable of up to 50-centimeter resolutions — and a wide-angle camera that provides color information.

“We have a fire hose of data. We return about 440 gigabits of image data a day,” says Watters. “Just the narrow-angle cameras themselves have returned well over a million images of the moon. It’s more digital data than every other planetary mission sent out has collected, by far.”

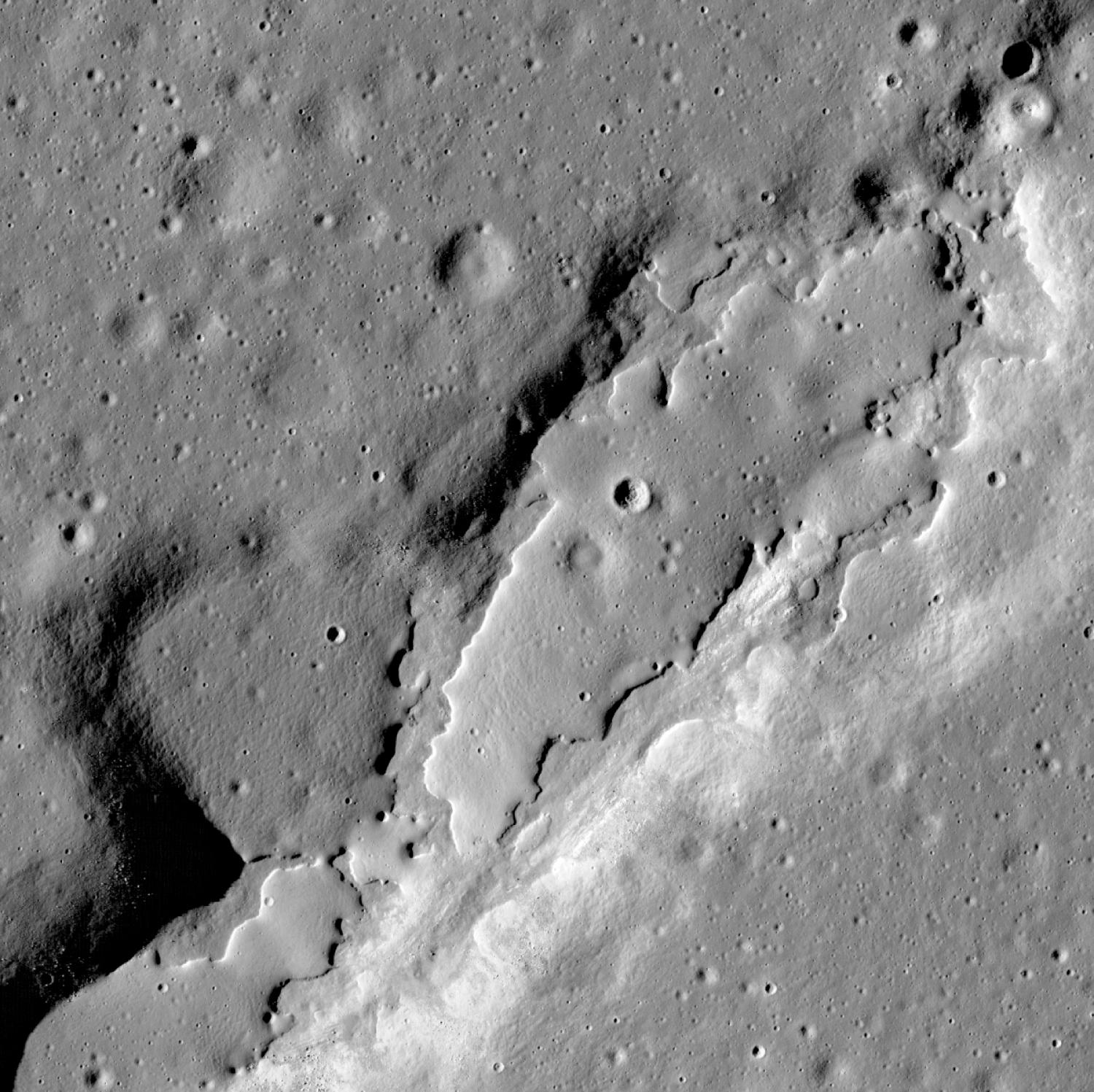

Among the lunar insights we’ve gained is the concept that the moon is shrinking. In 2010, the orbital camera team announced the discovery of a number of young, small cliffs called lobate scarps at various latitudes around the moon. (Hear Watters discuss the discovery in this SciFri segment.)

The finding, reported in Science, supported a theory that the moon has contracted as its molten core has cooled, causing sections of crust to crack and jut out over other sections, resulting in lobe-shaped cliffs. The team estimated that this contraction has diminished the distance between the lunar surface and center by no more than 300 feet. (The moon isn’t the only celestial body in our solar system to sport lobate scarps; they also appear on Mercury and Mars.)

Subsequent analysis of thousands of these lobate scarps revealed a pattern indicating that Earth’s tidal forces are contributing to their orientation. “Literally, the moon is being stretched and relaxed as part of the tidal flexing that comes from the Earth’s influence,” says Watters, who published a paper on the finding this past fall in the journal Geology with members of the orbital camera team. (Hear more about the finding in this SciFri segment.)

Watters hopes the orbiter's mission is extended once again — it winds down in September — so that he and his teammates can follow up on hunches based on the data they’ve already collected. For instance, “if some of the force [on the moon] is coming from Earth, there’s no reason not to believe that the moon is tectonically active right now,” he says.

Figuring out which areas are prone to moonquakes and how frequently space rocks bombard the moon would be useful for any future manned lunar missions, says Watters.

For his part, he suspects we’ll be back. “I do think that the moon is an important stepping stone in human exploration of the solar system.”

This story was first published by Science Friday with Ira Flatow.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!