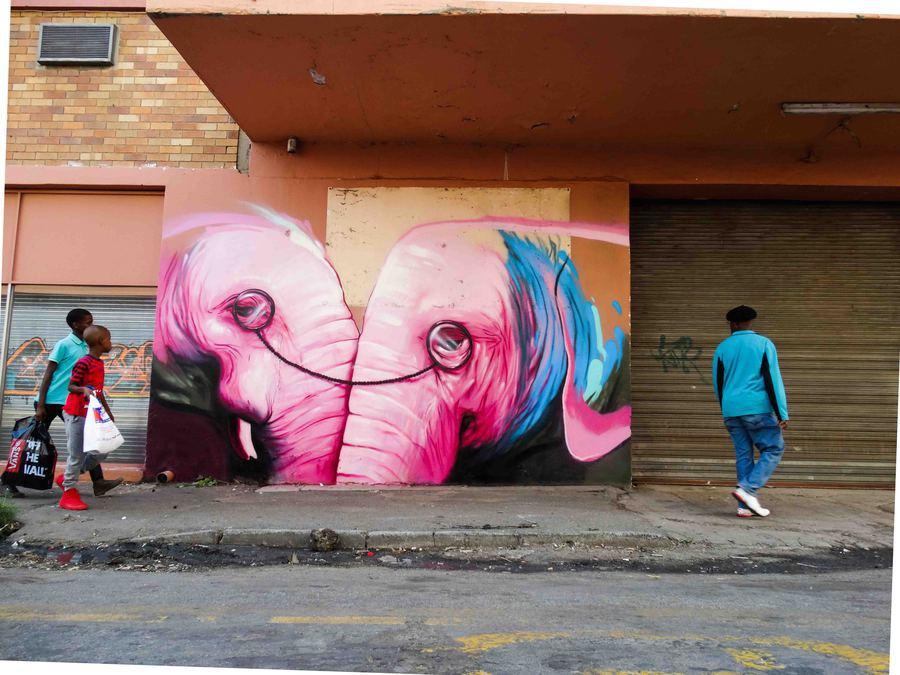

"Out the Box," done for Red Bull's One Upon A Town project, Kachelhoffer, Western Cape, South Africa 2015.

It starts with a blank wall — a concrete canvas. Can in hand, a stroke of color, then another and another until what was a wall becomes a work of art. The tag is the finisher, letting the world know the mural's creator.

Graffiti was cultivated in the streets of New York in the 1970s, and in the '80s the art form made its way to Africa. There, it's a less established medium, but has a growing community of vibrant artists. Still, they don't get as much media attention or representation at international festivals as artists from Europe or North America.

"There’s a lot of underrepresentation. When you go to festivals they just put you on like a footnote and it ends there," says Kenyan street artist Wisetwo. "If you do your research well, there’s a lot of good artists in Nairobi, there’s lots of good artists in Tunisia."

Here are three artists doing working to get Africa's graffiti community more visibility.

Falko One

In 1988, nearing the end of apartheid in South Africa, grafitti artist Falko One began his journey into the subculture in Cape Town at one of the only clubs where people of color people could go to party. There he was introduced to the world of hip hop and grafitti.

Today Falko is credited with much of the development of graffiti in his country. Through a letter exchange in the '90s, Falko helped facilitate a network between budding South African graffiti artists and industry veterans in Europe so they could learn from one another. In 1996, he started the first graffiti competition in South Africa, called Battle With Vapours, which continued to be hosted for several years.

His work decorates building all over the Cape Flats, the country and other towns and cities across the globe. His art, he says, has been described as fantasy and poetic. He says it's an interpretation of the world around him.

“What influences me in general is social and political observations that I make,” says Falko. “But I don’t spoon-feed it. It’s not blatant. I do realize that the communities I go into, I am a visitor … I don’t like going into communities and forcing my point of view on everybody. … I do a little artwork, placing visual aesthetics firstly and then afterwards I’ll add in a little message, and it varies from area to area.”

He studied graphic design but didn't finish school.

“Graffiti was not something I consciously decided to do,” says Falko. “It was elements and people around me that forced me to do graffiti.”

He met King Jamo, one of the hip-hop performers from club The Base, his second night going there. King Jamoshowed him the flag for his crew, with the word Zulu written in graffiti. He told Falko they were looking for young graffiti artists to join his team. From then on, Falko says, he was hooked.

“I have a pretty obsessive personality," he says. "And once I got into it, it was all I could think of.”

Wisetwo

In the bustling city of Nairobi, Kenyan artist Wisetwo has been working in street art for more than a decade.

From childhood he had an interest in art, as he believes all children do.

“Isn’t every child just interested in painting?” he asks. “Then it just depends on how far society hits you and brainwashes you and tells you science and business is more important than art.”

Although not convinced he should put away his paintbrushes and spray cans, Wisetwo went to college and got a degree in international relations — just “as a back-up plan,” he says.

But painting is his passion, and it’s taken him all over the world — from Canada to Yemen. Most of the work he does is for his own pleasure, shown in festivals and the gallery of the streets, but he has done commissioned work, usually in his home city, for NGOs such as the United Nations.

Wisetwo has done political work in the past but prefers to steer clear of politics in his art. In 2013, around the time of the Kenyan presidential elections, with the permission of the Rift Valley Railway, a group of Kenyan artists painted a 10-car commuter train with peace messages. Kibera, the slum the rail runs through, experienced a lot of violence during the 2007 election. It was called the Kibera Peace Train, aimed at promoting peace.

“Trying to merge the [politics and art] is not an easy task,” Wisetwo says. “That’s not the concept of my expression. This world has too many problems. Trying to fix them is not my thing. I just paint, make places look beautiful.”

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

Last year Wisetwo had his first solo exhibition in Paris.

His show featured murals of African masks with patterned work influenced by the cultures of ancient civilizations such as the Mayans, Aztecs and Mesopotamia and embraces Egyptian hieroglyphs. It’s this work that Wisetwo says truly represents his style.

“If you look at street art and graffiti, you find a lot of American and European influence. Just that I am raised in a different continent doesn’t mean I should adopt an American culture of painting or a European culture of painting," says Wisetwo. "People do that all the time. So I just decided to put it true to the roots, paint where I am coming from and what interests me a lot from ancient texts and ancient cultures. This is the best way I can express myself."

_0.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

Vajo

Vajo out of Gabès, Tunisia, is a force to be reckoned with. He was propelled to the international stage in 2011 during the Tunisian Revolution, also known as the Jasmine Revolution, which was the first in a wave of uprisings in the Arab world called the Arab Spring.

Vajo was featured in a documentary called PUSH Tunisia, which brought together a collection of Tunisian skateboarders, activists and street artists.

They came to be known as The Bedouins. The group promoted peace in the war-torn country through their crafts. They turned the ransacked mansion of a member of the former ruling family into a hangoutfor creative minds.

In summer of 2014 Vajo participated in Djerbahood, a project organized by theParisianItinerrance Gallery involving 150 artists of 30 different nationalities. They turned the village of Erriadh on the of island of Djerba, Tunisia into an "open-air museum", freely painting as many walls as they liked. The island is a mjor attraction for the country and the works of these artists have made it even more so.

Vajo is also trying to keep the medium going: he participated in a workshop funded by Tunisia's US embassy to give children a crash course in the art of graffiti.